NINES and Digital Archives

Our discussion of TEI has given you a sense of some of the work that can go into creating digital editions of texts. Indeed, encoding texts in this way is often the first step in a long process of preparing documents, historical or otherwise, for presentation and distribution on the web. In this section, we’ll talk more about the stakes of putting digital collections like these online and help you understand some of the archives that are out there for you to use.

One good reason to put a collection online is be to increase access to the materials. After all, a manuscript kept in a museum requires that someone go to that location in order to read the document. An online version can reach a wider audience than a physical copy. However, putting materials on the internet raises a variety of legal and financial issues. After all, these digital resources require a great deal of time, funding, and energy to produce. Imagine you are the curator of an archive:

- Will you make your materials freely available to anyone with an internet connection?

- Will you require payment to see them?

- Why?

If you have ever tried to access a resource from an online newspaper only to be told that you need to subscribe to see their content, you have encountered such paywalled materials. Resources like these can be juxtaposed with open access materials. While there are different levels and variants, open access broadly means that the materials are available with little to no restrictions: you can read them without having to pay for them. For many, the choice is an ethical and a political one. But open access materials do raise serious financial questions:

- Keeping materials online requires sustained funding over time. How can open access work be maintained if they are presented for free?

Once materials are put online, it is possible to connect them to a wider, global network of similar digital materials. In the same way that a library gathers information about its materials to organize in a systematic way (more on metadata in our lesson on “Problems with Data”), scholars and archivists have to oversee this process for this networking to happen. For instance, technical standards shift (TEI tags can change over time), so archival materials require constant maintenance. If you have ever used a digital archive, you have benefited from a vast and often invisible amount of labor happening behind the scenes. The hidden work of gallery, library, archive, and museum (or GLAM) professionals ensures that our cultural heritage will remain accessible and sustainable for centuries to come.

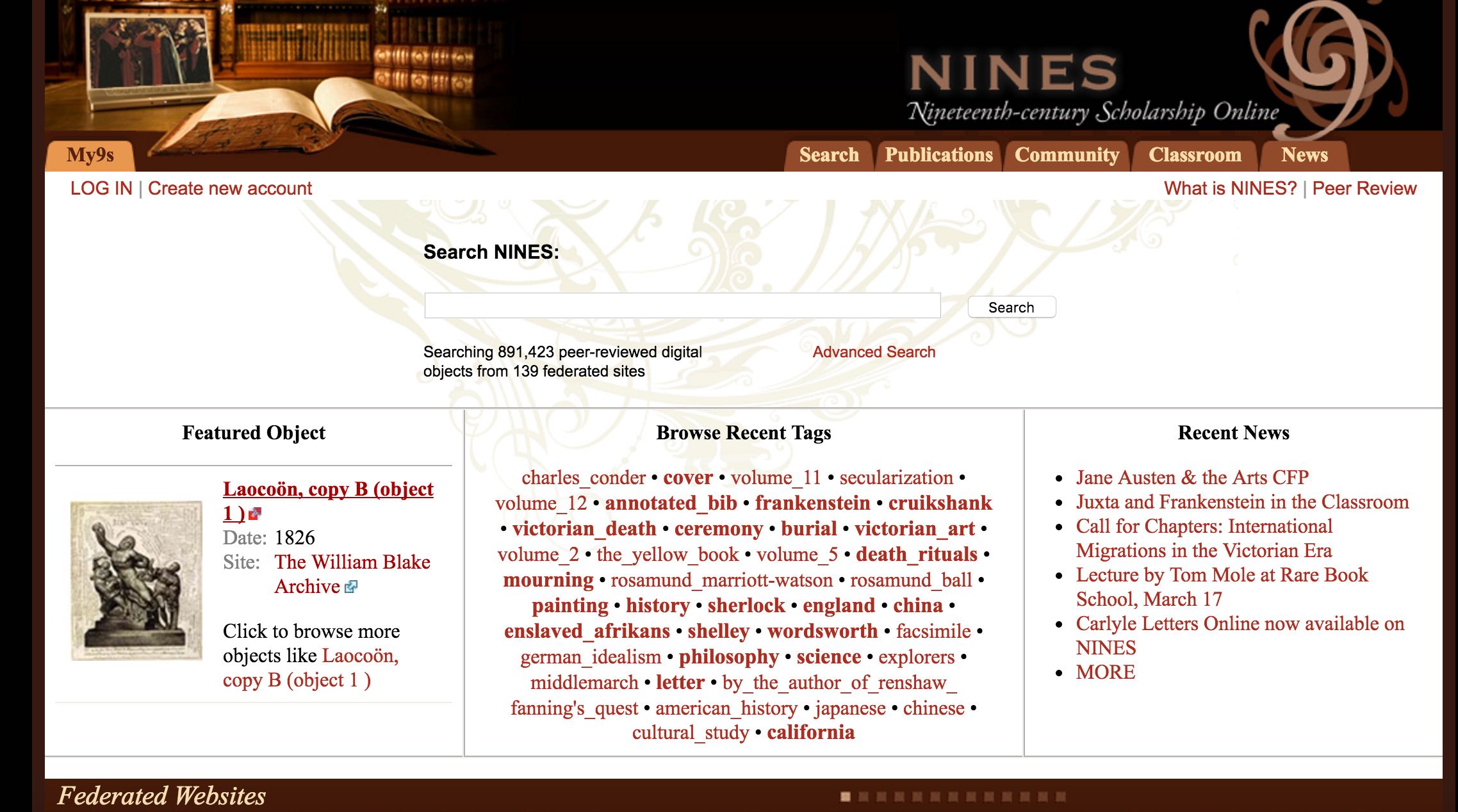

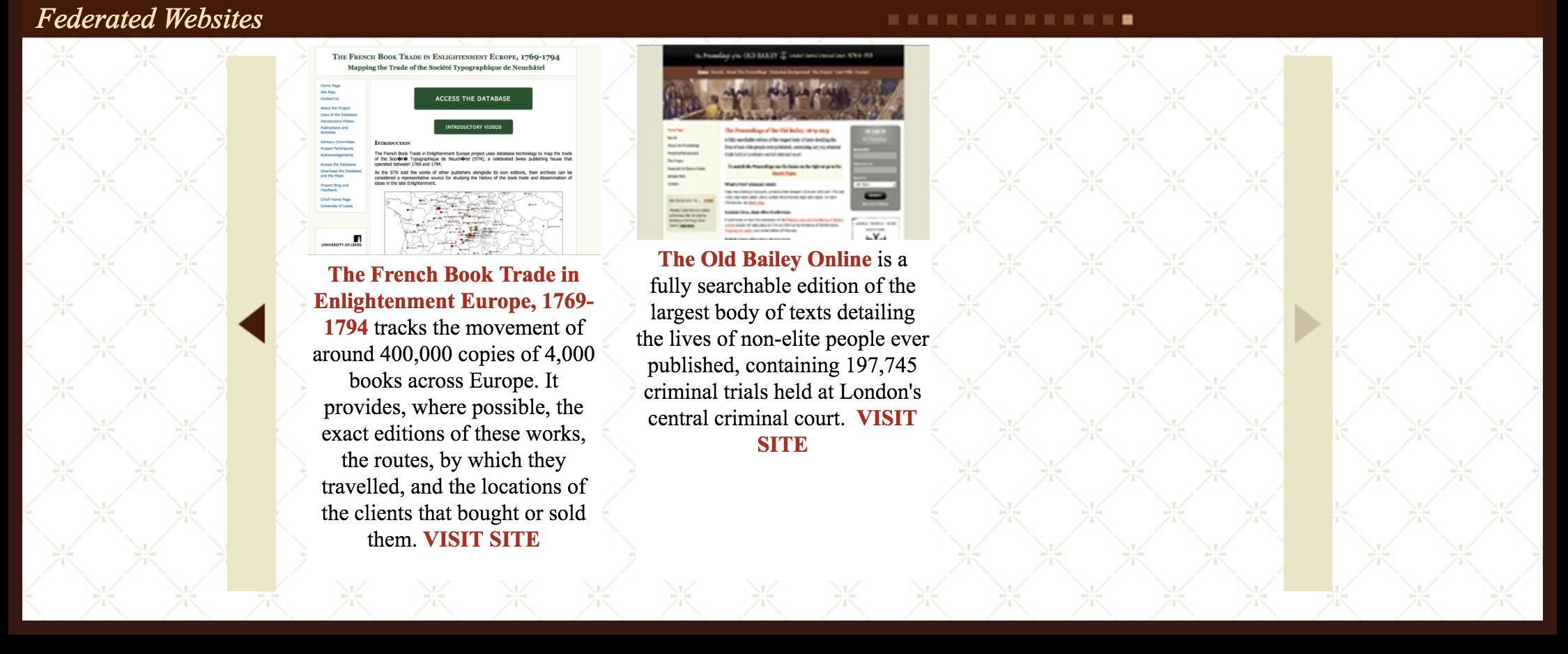

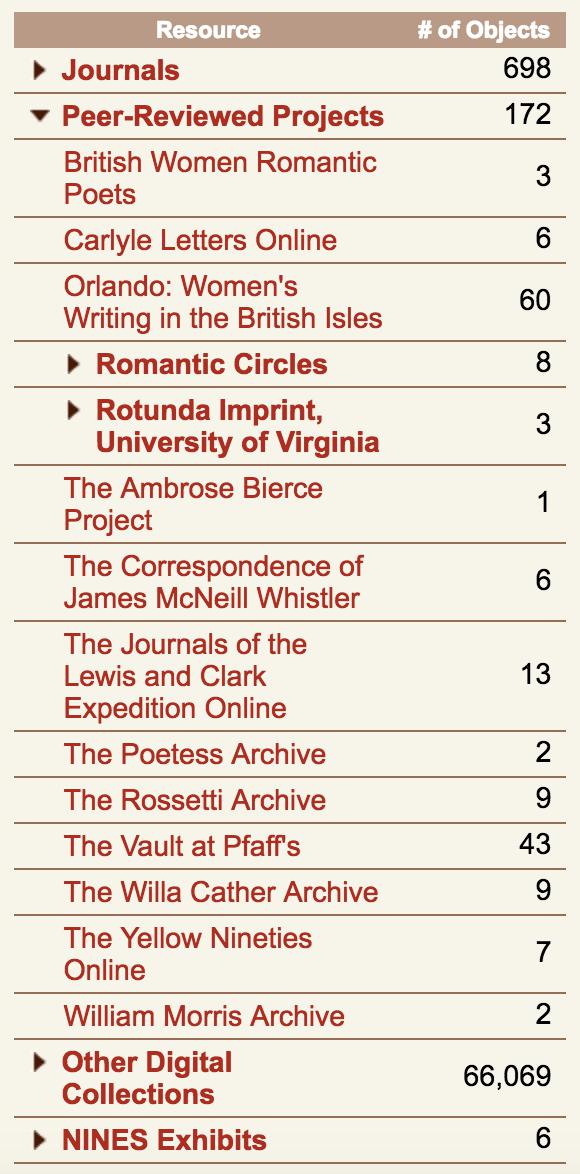

The Networked Infrastructure for Nineteenth-Century Electronic Scholarship (NINES) is one such digital humanities organization that attempts to facilitate the archiving process by gathering archived materials pertaining to the nineteenth century. You might think of NINES as something like a one-stop shop for all your nineteenth-century archival needs. It gathers together peer-reviewed projects on literature and culture that different research teams around the globe put together; some focus on an individual author, others on a genre (periodicals or “penny dreadfuls”) or a particular issue (disability or court cases). If you go to the site and scroll through “Federated Websites,” you’ll see the range of projects you can access from NINES, from one on the eighteenth-century book trade in France to another featuring the letters of Emily Dickinson. For the purposes of this class, you’ll notice that some of the projects will be extremely useful to you, such as the Old Bailey Online, which contains trials records from London’s central criminal court. Others, such as a project on the journals of Lewis and Clark, won’t be relevant for this class, but might be for others you are taking.

You might also notice that NINES has a relatively expansive view of what the nineteenth century is, since this site includes projects that deal with the late eighteenth and early twentieth century. Historians often talk of the “long nineteenth century” as the period from the beginning of the French Revolution in 1789 to the outbreak of World War I in 1914. (In other words, historians of the nineteenth century like to claim big chunks of other people’s time periods.)

Archives submit themselves for affiliation with NINES so that their materials can be searchable alongside other NINES sites, but first they must pass a rigorous process of peer review first. Academic journals rely on peer review to ensure that scholarship meets particular standards of rigor and relevance; it is a bit like quality control for scholarly writing. The peer review process typically involves submitting an article or book to a series of reviewers who write letters in support or rejection of the project and offer suggestions for improvement. The process is double-blind; the reviewers don’t know who the authors are and vice versa. Should the piece pass, it moves onto publication and receives the explicit seal of approval from the publication.

Why go through peer review?

Peer review sounds like a lot of work (and it is), but going through this process has benefits for you as an author. For one, it’s a way to get suggestions for improvement. Scholars also see peer-reviewed projects as being more prestigious than non-peer reviewed works and, for the purposes of promotion, they “count” more than non-peer reviewed works. Peer review allows faculty members to assure their colleagues that their work is worthy of funding.

Digital projects, in particular, take an extraordinary amount of work and resources, so it makes sense that their contributors want credit for their work. But it can be difficult to evaluate something like an archive, since scholars are primarily trained to produce and evaluate secondary sources as opposed to primary-source repositories. Digital projects also require reviewers who understand not only the content but also the technical aspects of a project.

One of the early missions of NINES was to faciliate peer review for digital projects. By assembling digital humanities scholars that could evaluate digital archives and attest to their successes or flaws, project coordinators could better make their work available and understandable to colleagues who weren’t working with digital material. So, say you worked on The Old Bailey Online and are up for a promotion at your institution; submitting this project to NINES for peer review is a way to make sure that your colleagues recognize the hard work you put into this project. Once reviewed, NINES makes the archival materials available for searching alongside other peer-reviewed projects. (You can see an example search of The Old Bailey Online here. Because the Old Bailey’s archival materials are part of NINES, a search for ‘old bailey’ in NINES reveals objects not only in NINES, but also in a wide range of other archives.)

What does peer review mean for you as a user of an archive?

If you’ve made it this far in life, you’ve probably realized that you can’t trust everything you find on the internet. In this case, knowing that something is peer reviewed allows you to put more trust in what you find on NINES than what you find elsewhere; you know that other scholars in the field have signed off on this material and think it is a worthy project.

Why else should I use NINES?

Beyond the fact that you can have a lot of confidence in the projects you find here, NINES is going to make it easier for you to find things. For one, you might not have known about all these different projects. NINES has also made sure that these projects “play nice” with each other (a.k.a. interoperability), which means you can find references to a particular topic or word across these projects with a simple search.

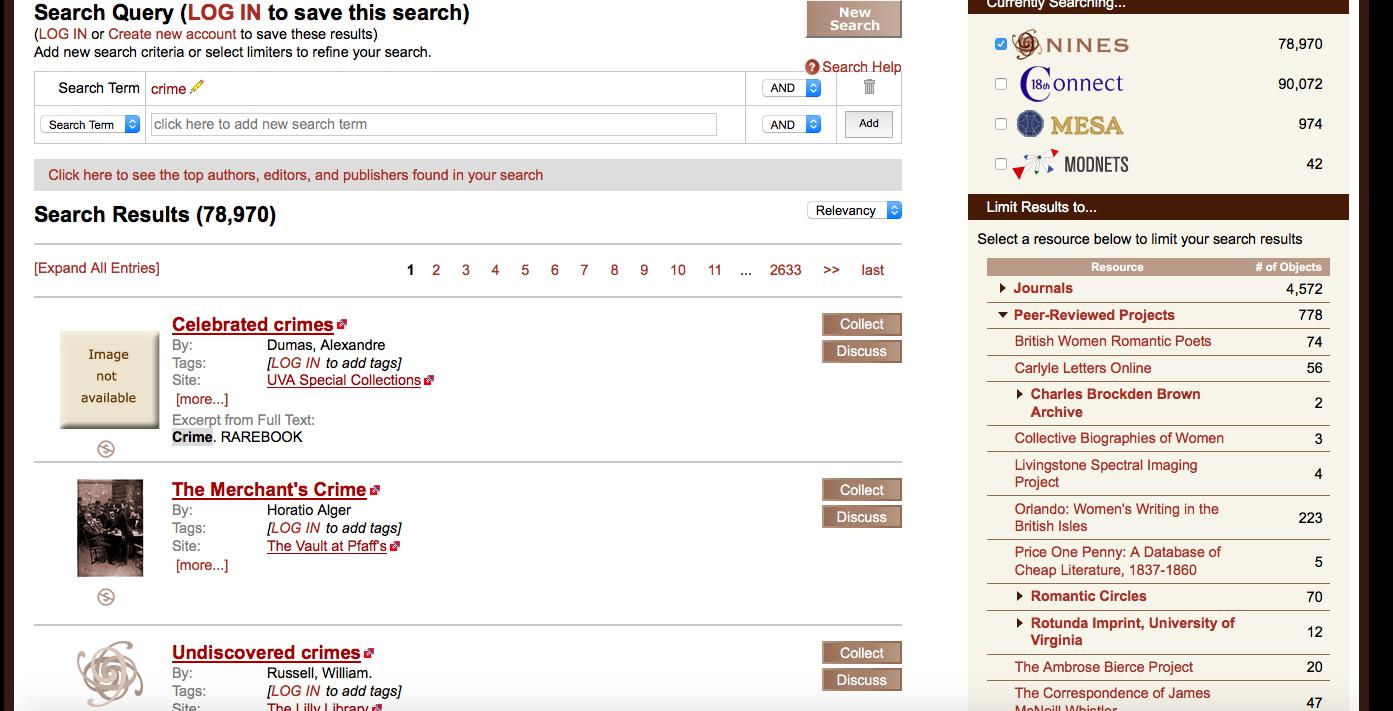

Doing a search for “crime” gets you all the references to this term in all of the different projects linked to NINES, saving you from having to search each individual archive.

One warning: only some of the results you get in the left pane are to material from the online projects affiliated with NINES. In other cases, NINES is searching library catalogs where the material is not available digitally. In this instance, if you wanted to read the first work, Alexandre Dumas’s Celebrated Crimes, you would have to drive to Charlottesville and go to UVA’s Special Collections Library.

-

What archives do you use on a regular basis?

-

What kinds of work do you imagine went into them?