Where to go Next

You’ve come a long way! Thanks for sticking with us!

You’ve learned a lot. Thought a lot. Read a lot. What comes next? We’ve talked about a bunch of different approaches to text analysis, so hopefully you have some ideas about things that interest you. One way forward might be to experiment with new tools. Or you could delve more deeply into a particular approach that piqued your interest. Perhaps while moving along you found yourself wishing that a tool could do something that it just wasn’t set up to do.

- “If only it would do X!”

Maybe you can make something for yourself to do X!

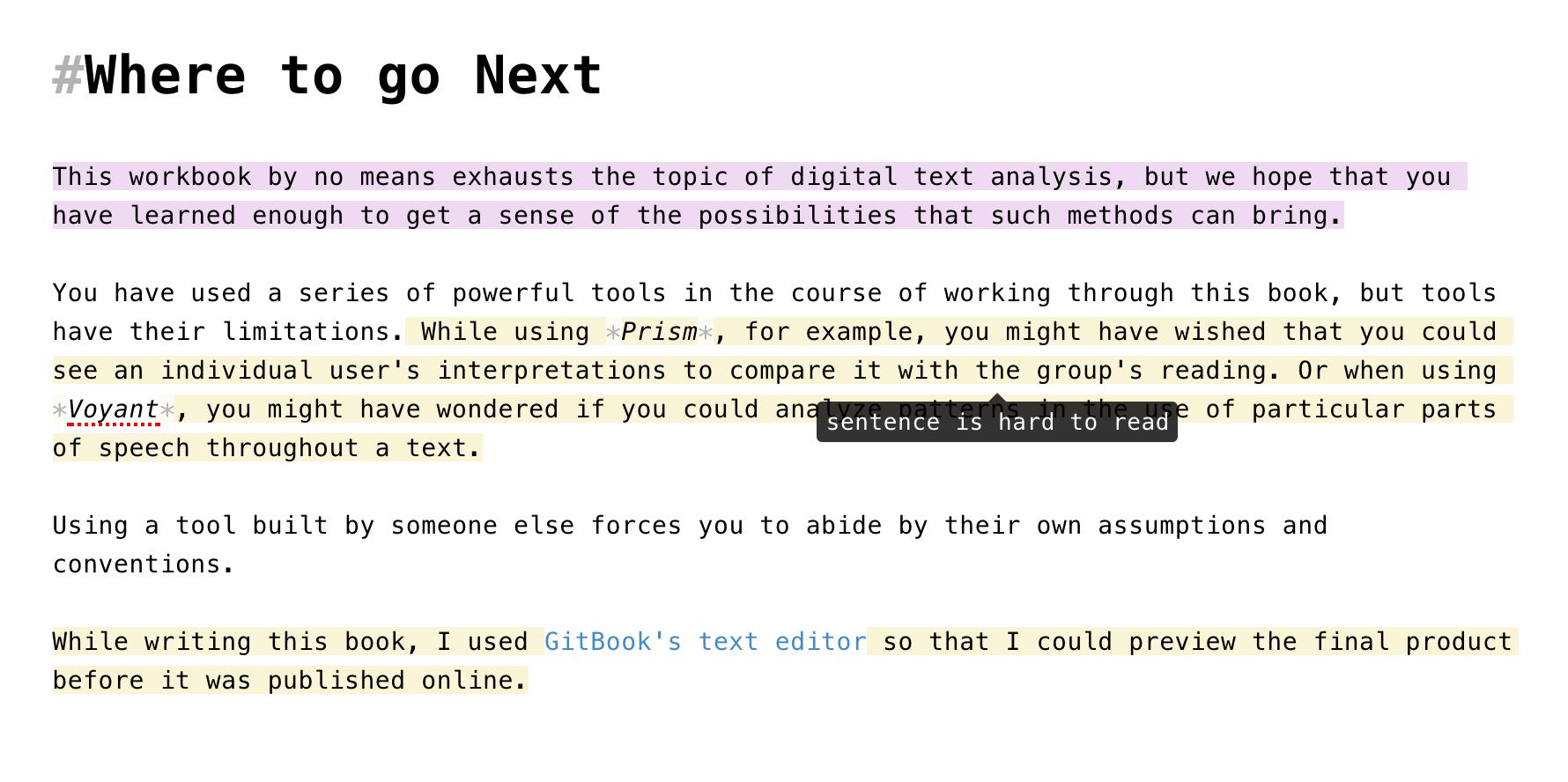

While writing this book, we used GitBook’s text editor so that we could preview the final product of our writing before it was published online. But the text editor has all sorts of added features. For example, it offers a style editor that suggests certain kinds of sentences might contain difficult syntaxs or formulations. Potentially useful, right? Maybe, but we turned it off right away. We found it really annoying to type while our text was screaming at us like this:

The most irritating thing was that we could not tell what metrics they were using to diagnose our writing. What makes a sentence difficult? The number of words in each sentence? The number of clauses? Subjects in particular positions? We have all sorts of opinions about why writing might be unclear, but, as best we could tell, the editor was mostly basing their suggestions on the number of words in each sentence. We turned the feature off and went on with our lives, but not before noting a truism of working digital humanities: using a tool built by someone else forces you to abide by their own assumptions and conventions. We could not change how the style checker worked beyond the minimal configuration options given to us in the platform.

You might have had similar feelings while reading this book. You have used a series of powerful tools in the course of working through this book, but each one has its limitations. While using Prism, for example, you might have wished that you could see an individual user’s interpretations to compare it with the group’s reading. Or when using Voyant, you might have wondered if you could analyze patterns in the use of particular parts of speech throughout a text. Or maybe you were really interested in sentiment analysis or topic modeling. We didn’t really offer tools for either of these approaches, because they quickly get a little more technical than we wanted. You need to be comfortable with some basic programming approaches to use tools of that nature.

A logical next step for you might be to learn a programming language that can help facilitate textual analysis. Python and R are two widely used languages for these applications with a wealth of resources to help get you started. Exploring a new programming language takes time and dedication, but it can help guide you towards new types of questions that you might not otherwise be able to ask. Learning to program can help you determine what types of questions and projects are doable, and which ones might need to be let go. Most importantly, it can help you realize when using a tool someone else has built is better and easier than reinventing the wheel. While we would have loved nothing more than to turn you all into self-sufficient Python gurus, we believed that the purposes of this introduction could be better served by showing you what was possible first by tools and case studies. If you want to go further, you always can.

This workbook by no means exhausts the topic of digital text analysis, but we hope that you have learned enough to get a sense of the possibilities that such methods can bring. Check out the Further Resources page for other approaches, inspirations, and provocations. If, while reading the book, you found errors or sections that need clarification, please drop a note on our GitHub issues page.

Thanks for reading!

Brandon and Sarah