Prism Part Two

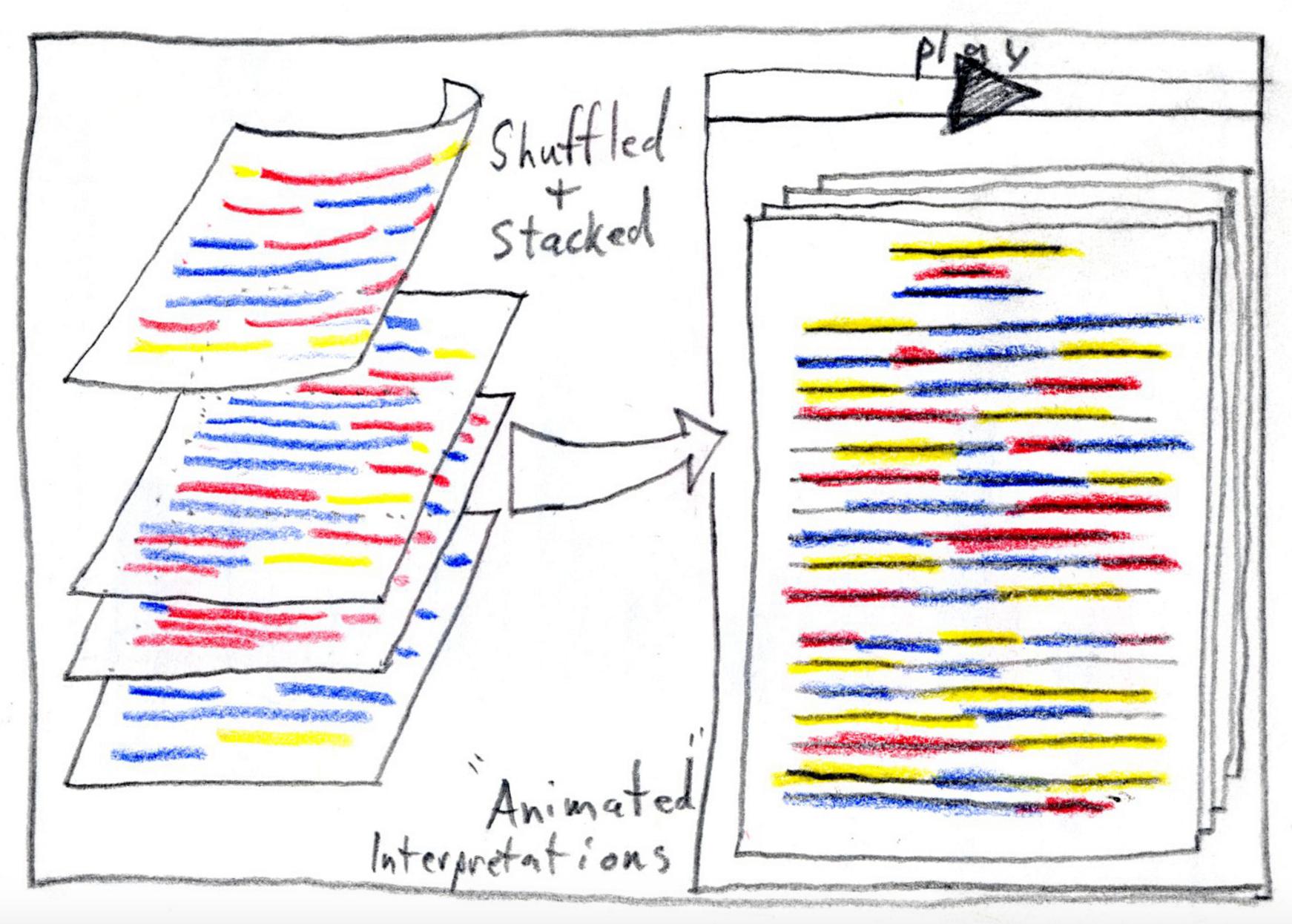

Think back to Prism and the transparency game. So far we have only really focused on the single transparencies and the interpretations one individual supplied. But the crucial last element of the game involves collecting the transparencies and stacking them. Hold the stack up the light, and you get a whole rainbow: you can see what everyone thinks about the text. Prism’s visualizations offer one way of adapting this activity to a digital environment.

In this photo from the “Future Directions” page for Prism, you can see the prototype for another possible visualization that would shuffle through the various sets of highlights. Even without this animated interpretation, Prism allows you to get a sense of how a whole group interprets a text. The program collections you markings along with those of everyone who has ever read that text in Prism. We can begin to get some sense of trends in the ways that the group reads.

Prism was designed as a middle road between the two types of crowdsourcing projects that we discussed in the last section. By asking users to mark for a restricted number of categories, it can quantify those readings and visualize them in interesting ways. But it also asks for readers to actually read the text - interpreting a document along certain guidelines still asks readers to exercise the full range of their powers as thinking people. For this reason, the designers of Prism see it as crowdsourcing interpretation.

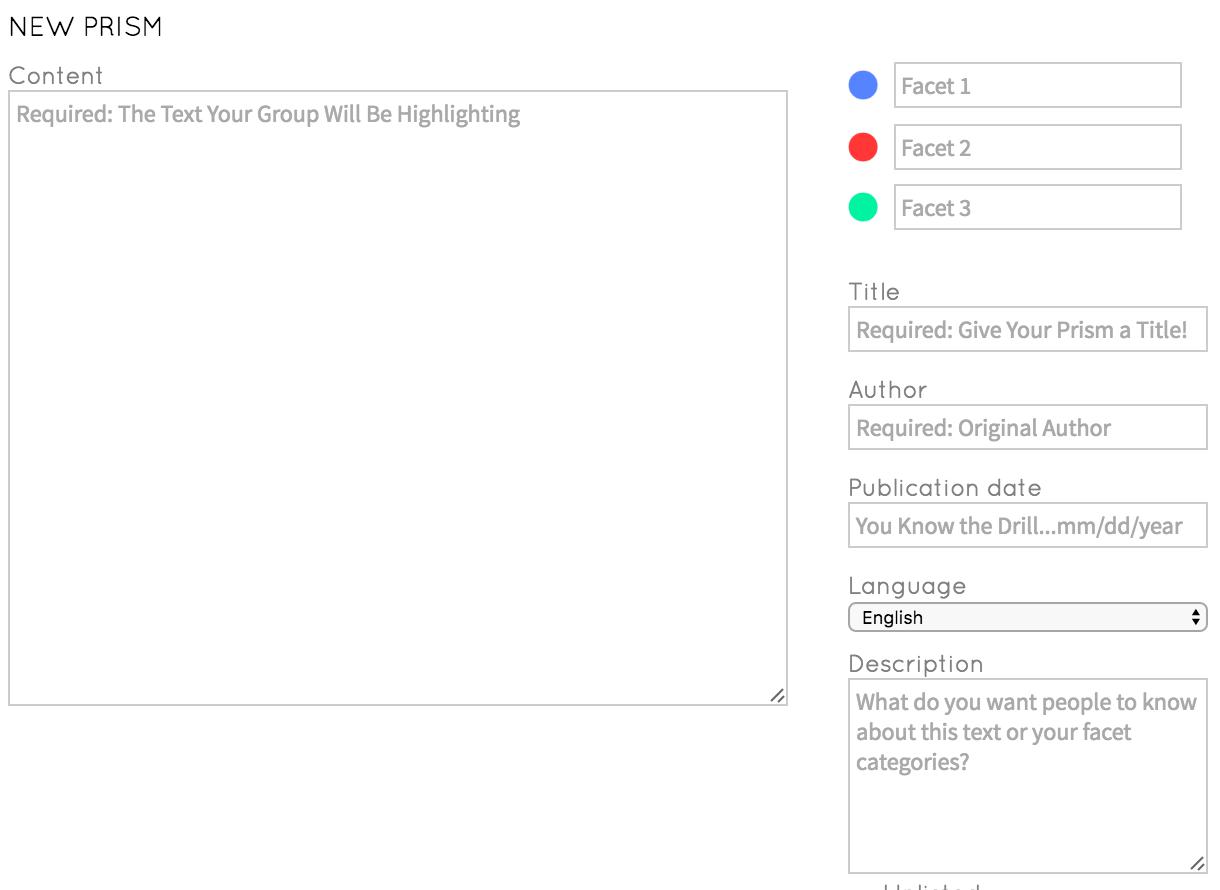

Prism offers a few options to facilitate group reading. Most importantly, it assumes very little about how its users will use the tool. Anyone can upload their own text as a Prism and, within certain guidelines, adapt the tool to their own purposes. When logged in, you can create a Prism by clicking the big create button to pull up the uploading interface:

You upload a text by pasting it into the window provided. Prism does not play well with super long texts, so you may have to play around in order to find a length that works for the tool as well as for you. The three facets on the right correspond to the three marking categories according to which you want users to highlight. The rest of these categories should be self-explanatory. Note, however, that you will only be able to give a short description to readers: your document and marking categories will largely have to stand on their own.

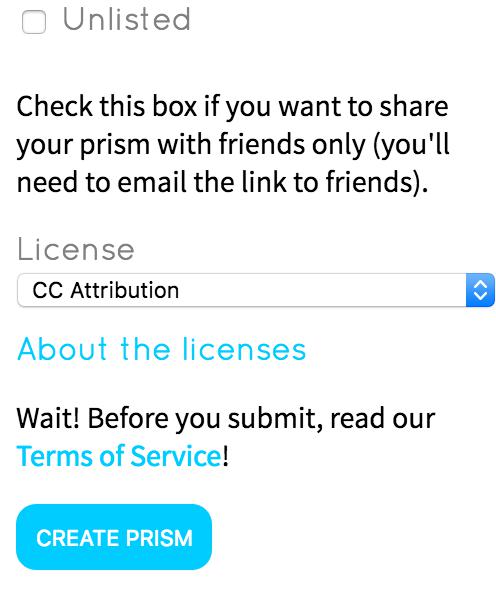

Below these main parameters for your text, you will be asked to make some other choices that may be less intuitive.

By default, Prism assumes that you want the text and all its markings to be made available to the public. Selecting unlisted will make your Prism private so that only to people to whom you send the URL can view it. Once you create the Prism, you will want to be extra certain that you copy that URL down somewhere so that you can send it out to your group.

Prism will also ask you what license you want to attribute to your materials. Many of the choices offered here are creative commons licenses, but you can also choose public domain or fair use depending on your needs. If you are unsure, you can always select no license, but it would be worth doing a little research about the materials you are uploading to find out their legal status.

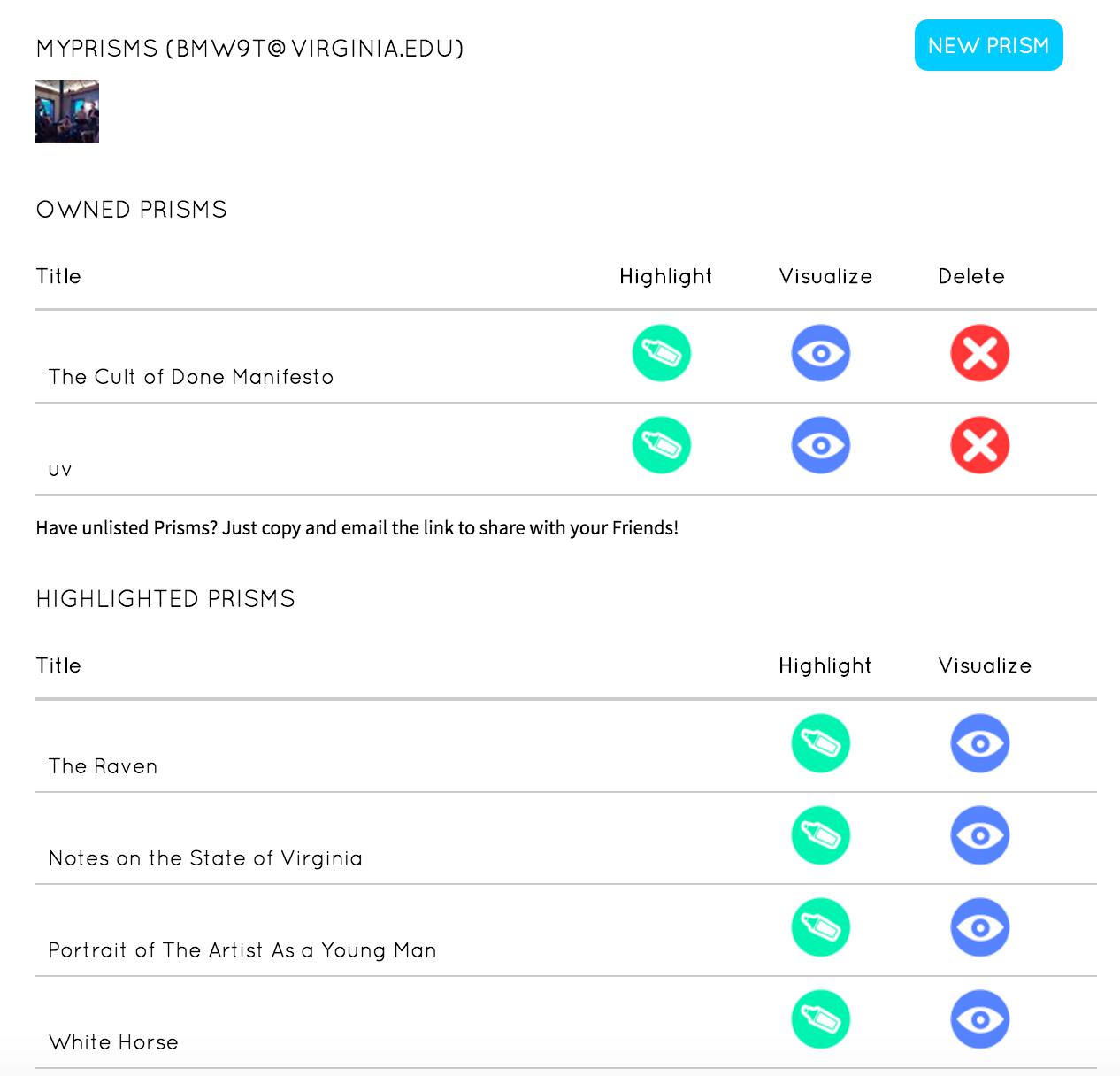

Once you upload a text, the easiest way to find it is to go your personal page by clicking the “MYPRISMS” link from the top menu. In this profile page, you can easily access both the texts that you have uploaded as well as the ones that you have highlighted but that belong to others (quite handy if you lose the URL for an unlisted text).

With these tools, you can upload a range of texts for any kind of experiment. It is tempting to say that you are limited by your imagination, but you will run up against scenarios in which the parameters for the tool cause you headaches. That’s OK! Take these opportunities to reflect:

-

What will the tool not let you do?

-

Can you imagine good reasons for these limitations?

-

How would you design a different tool?

As you work through Prism, think critically about the concept of crowdsourced interpretation.

-

Do you feel that this sort of work is fundamentally more empowering than the kind we saw with Typewright, Recaptcha, and Transcribe Bentham?

-

Are there other, better ways of facilitating group collaboration, digital or otherwise?