Voyant Part One

We will be using a tool called Voyant to introduce some basic topics in text analysis using cyborg readers.

Upon arriving at Voyant you will encounter a space where you can upload texts. For the following graphs, we have uploaded the full text of The String of Pearls, the 1846-1847 penny dreadful that featured Sweeney Todd, the demon barber of Fleet Street. Feel free to download that dataset and use it to produce the same results for following along, or upload your own texts using the window provided.

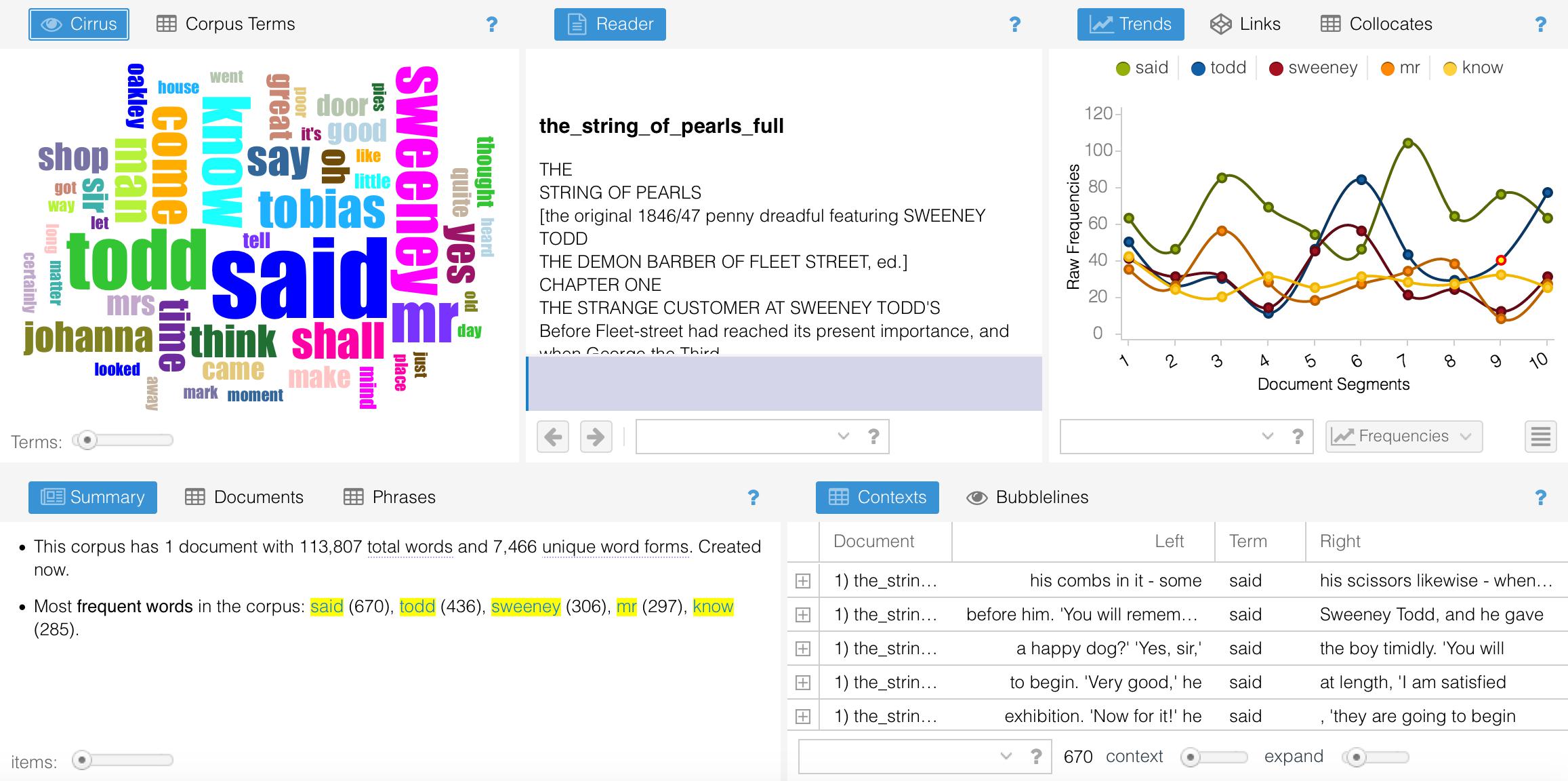

After Voyant processes your text you’ll get a series of window panes with lots of information. Voyant packages several features into one tight digital package: each pane offers you different ways of interacting with the text.

After Voyant processes your text you’ll get a series of window panes with lots of information. Voyant packages several features into one tight digital package: each pane offers you different ways of interacting with the text.

Voyant gives you lots of options, so do not be overwhelmed. Voyant provides great documentation for working through their interface, and we will not rehearse them all again here. Instead, we will just focus on a few features. The top left pane may be the most familiar to you:

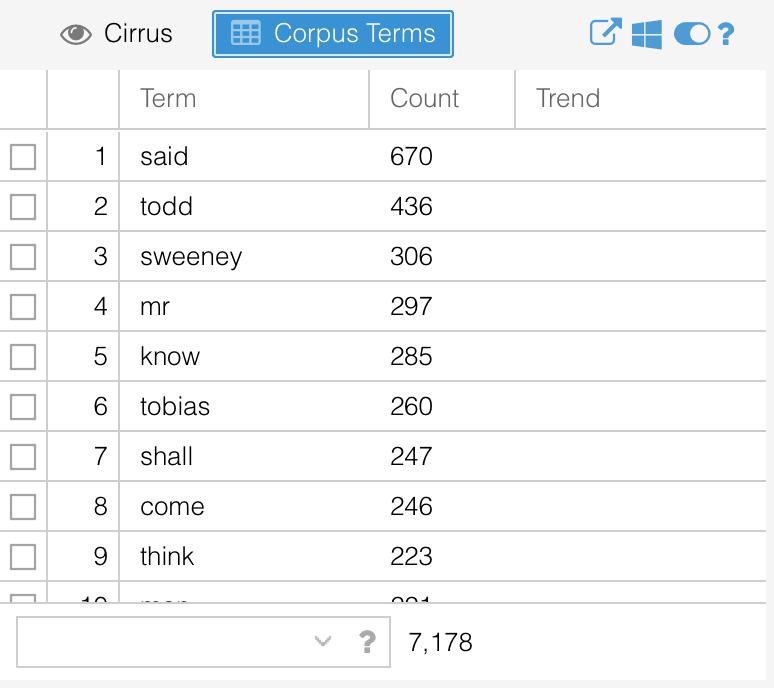

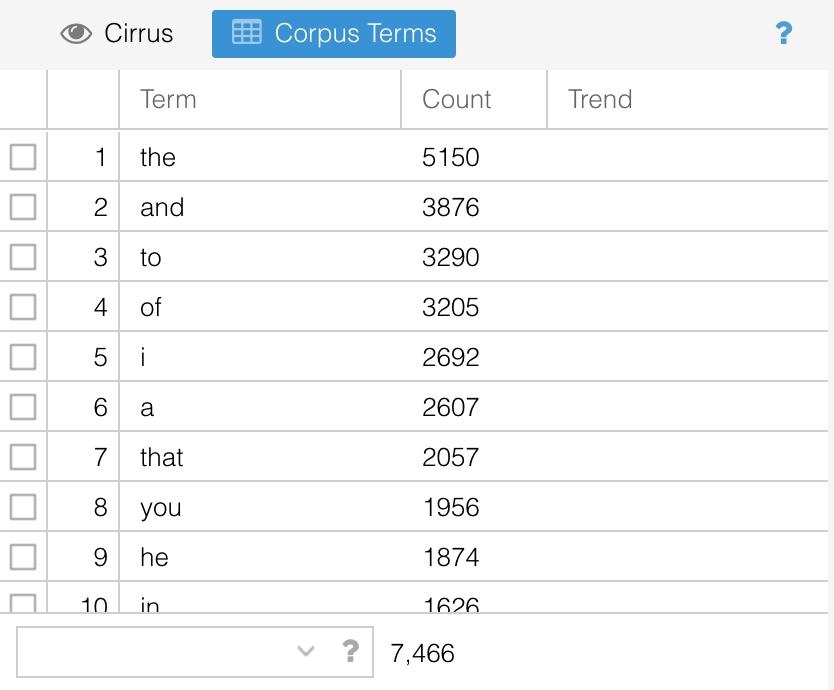

Word clouds like these have been made popular in recent years by Wordle. They do nothing more than count the different words in a text: the more frequent a particular word appears, the larger its presence in the word cloud. In fact, Voyant allows you to see the underlying frequencies that it is using to generate the cloud if you click the “Corpus Terms” button above the word cloud.

Concordances like these are some of the oldest forms of text analysis that we have, and computers are especially good at producing them. In fact, a project of this kind is frequently cited as one of the origin stories of digital humanities: Father Roberto Busa’s massive concordance of the works of St. Thomas Aquinas, begun on punch cards in the 1940’s and 1950’s. It was one of the first works of its kind and was instrumental in expanding the kinds of things that we could use computers to do.

Busa’s work took years. We can now carry out similar searches in seconds, and we can learn a lot by simply counting words. The most frequent words, by far, are ‘said’ and ‘Todd,” which makes a certain amount of sense. Many characters might speak and, when they do, they are probably talking about or to the central character, if they aren’t Todd himself.

Notice the words that you do not see on this list: words like ‘a’ or ‘the.’ Words like these, what we call stopwords, are so common that they are frequently excluded from analyses entirely, the reasoning being that they become something like linguistic noise, overshadowing words that might be more meaningful to the document. To see the words that Voyant excludes by default, hover next to the question mark at the top of the pane and click the second option from the right.

Use the dropdown list to switch from ‘auto-detect’ to none. Now the concordance will show you the actual word frequencies in the text. Notice that the frequency of ‘said’, the number one result in the original graph, does not even come close to the usage of articles, prepositions, and pronouns.

Words like these occur with such frequency that we often need to remove them entirely in order to get meaningful results. But the list of words that we might want to remove changes depending on the context. For example, language does not remain stable over time. Different decades and centuries have different linguistic patterns for which you might need to account. Shakespearean scholars might want to use an early modern stopword list provided by Stephen Wittek. You can use this same area of Voyant to edit the stoplist for this session of Voyant. Doing so will give you greater control over the tool and allow you to fine-tune it to your particular research questions.

There are some instances in which we might care a lot about just these noisy words. They can tell us how an author writes: those very words that might seem not to convey much about the content are the building blocks of an author’s style. Tamper with someone’s use of prepositions or pronouns and you will quickly change the nature of their voice.

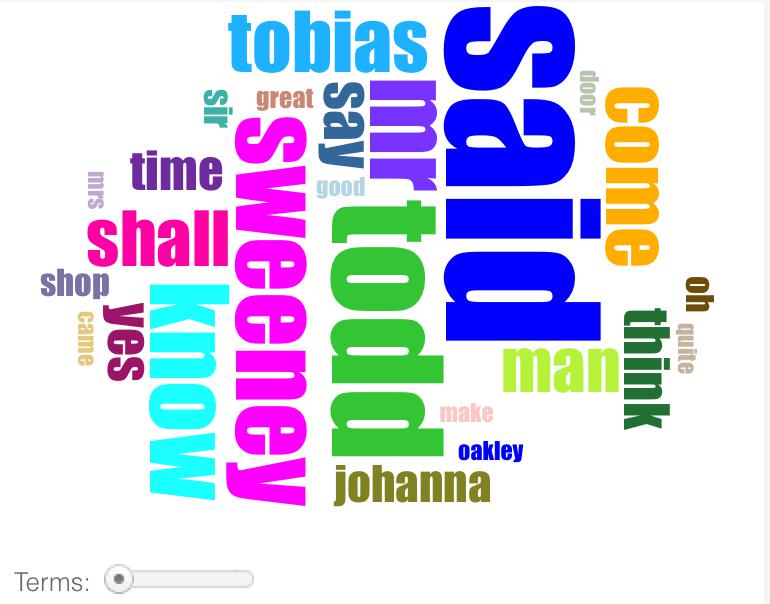

Let’s return to the word cloud. Using the slider below the word cloud, you can reduce or expand the number of terms visible in the visualization. Slide it all the way to the right to include the maximum number of words.

Just like the stopword list can be used to adjust the filters to give you meaningful results, this slider adjusts the visualization that you get. It should become clear as you play with both options that different filters and different visualizations can give you radically different readings. The results are far from objective: your own reading, the tool itself, and how you use it all shape the data as it comes to be known.

This is a good reminder that you should not think of digital tools as gateways to fixed and clear truths, either about historical periods or individual texts. Voyant may seem somehow objective in that it produces mathematical calculations and data visualizations, but now you’ve seen that you can easily alter the results. These techniques of “distant reading” are same as the models of “close reading” we talked about earlier in that both only lead to asking more questions and positing more interpretations.

That is a good thing.

Interpreting Word Clouds

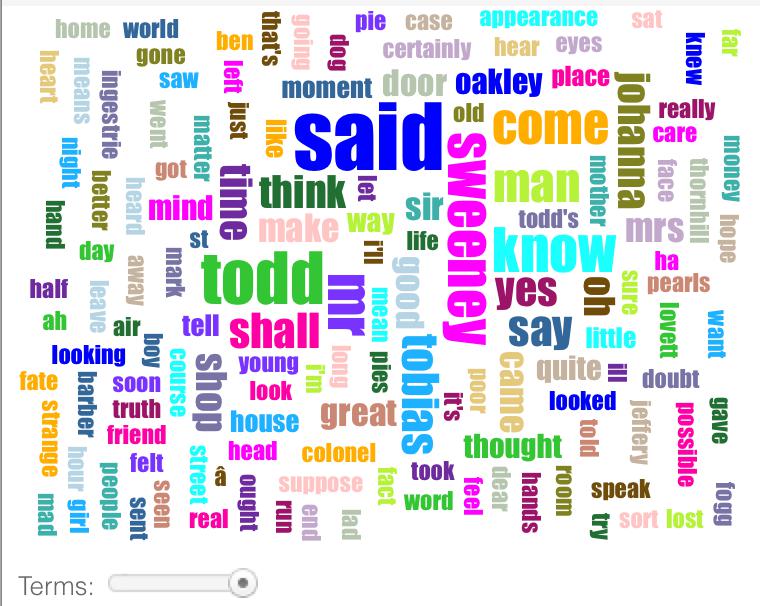

Given that what’s important about word clouds is not producing visualizations so much as the interpreting the results, you might ask: what does this help us learn about The String of Pearls?

For one, looking at these word clouds suggests that much of the vocabulary of this novel either refers to or exists in the context of speech. One of the most prominent words is “said,” but you also see “say” and “speak” and words like “yes,” “I’ll,” and “oh” which probably – although not necessarily – come from written dialog.

Additionally, most of the words are short, one or two syllables long. Penny dreadfuls like The String of Pearls were aimed at working class audiences: could the prevalence of these relatively ‘simple’ words reflect the audience of the text? In order to substantiate such a claim, we would probably want to look at other publications of the period to see whether or not this vocabulary was typical.

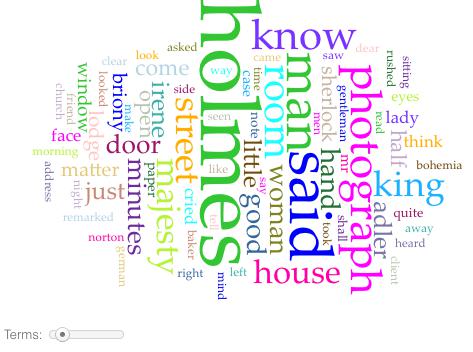

If we load Arthur Conan Doyle’s “A Scandal in Bohemia” into Voyant, you can see that we get quite different results. (Again, feel free to follow along.)

A quick glance shows that the most common words tend to be longer than those in A String of Pearls. Indeed, the three syllable “photograph” is one of the most frequently used terms in this short story, one written for a middle-class as opposed to working-class audience. So maybe the simple vocabulary of the penny dreadful is related to the nature of its readership.

But let’s not stop there! You may also notice that the word cloud for “A Scandal in Bohemia” has a lot of words related to high status: “king,” “magesty,” “gentleman,” and “lady,” for instance. In contrast, with the possible exception of the words “colonel” and “sir” in A String of Pearls, there are hardly any words in this novel that refer to rank. This gives you some indication that these two works are set in different social milieus in London.

Alternately, the types of words in these two works are not at all the same. The word cloud for A String of Pearls contains a lot of verbs (“shall,” “said,” “come,” “know,” “suppose,” “thought”), whereas that for “A Scandal in Bohemia” is made up of a lot of nouns, particularly those referring to places (“room,” “house,” “street,” “lodge,” “window,” and “adress”). This is an interesting thing to note, but you still want to think about what this means about the two different texts. Perhaps A String of Pearls is more concerned with action and on the excitement of people doing things than “A Scandal in Bohemia,” where the emphasis is on moving through and exploring different spaces. Or maybe all of these observations are artifacts of the visualizations, things that the word clouds suggest but that might not actually hold up under scrutiny of the data. More thinking is needed!

Some of these conclusions were probably pretty obvious as you read these two works (or portions of them). You probably picked up the fact that A String of Pearls is set in working-class London, whereas “A Scandal in Bohemia” takes place in a more elevated milieu. You might even have noticed a difference in vocabulary, even if using Voyant made these distinctions more apparent and gave you further data to back up any claims you were making about them. But you probably didn’t notice the emphasis on action vs. the importance of place in these two works. So this is a good example of how reading with one eye to the computer can lead you to new interpretations.

Further Resources

-

Geoffrey Rockwell and Stéfan Sinclair, the creators of Voyant, have a great book on using it for text analysis: Hermeneutica.

-

Shawn Graham, Ian Milligan, and Scott Weingart have an excellent introduction to working with humanities data in Exploring Big Historical Data: The Historian’s Macroscope.