Voyant Part Two

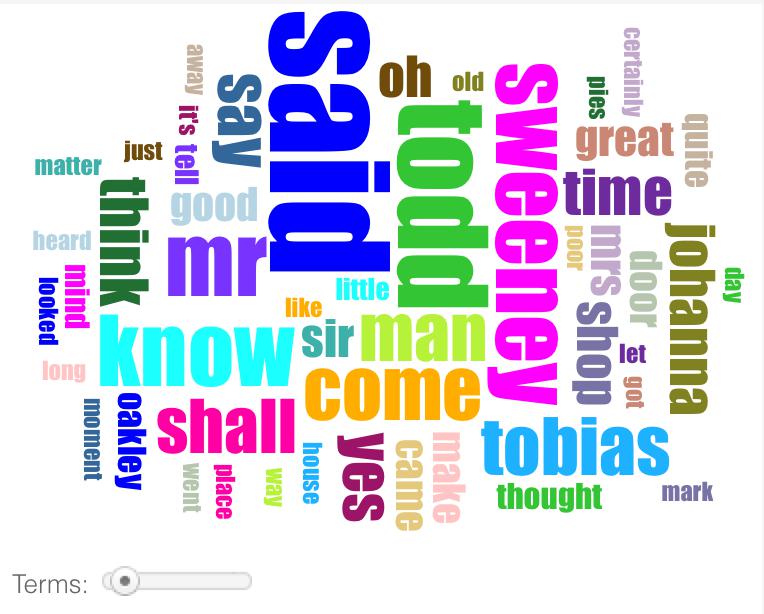

Let’s look at Voyant in a bit more detail. Feel free to download the Sweeney Todd dataset and use it to produce the same results and follow along, or upload your own texts using the window provided. Look back at the word cloud that Voyant gave us for The String of Pearls:

Using the standard stopword filter in Voyant, the most common word by far is ‘said.’ Taken alone, that might not mean an awful lot to you. But it implies a range of conversations: people speaking to each other, people speaking about different things. One of the limitations of frequency-based measurements like these is that they only show you a very high-level view of the text. Once you find an interesting observation, such as ‘said’ being one of the most frequent words in the text, you might want to drill down more deeply to see particular uses of the word. Voyant can help you just do that by providing a number of context-driven tools.

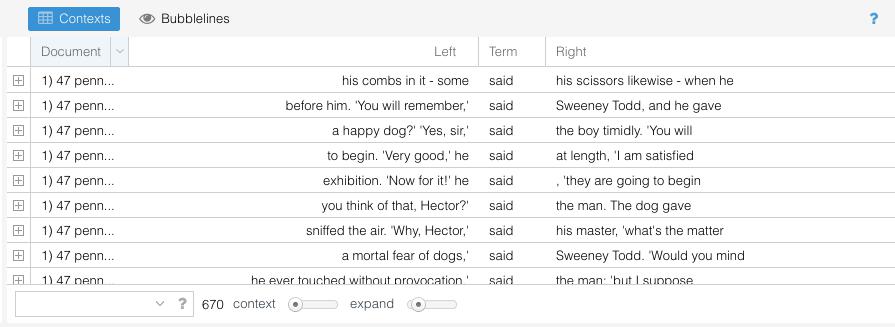

In the bottom-right pane, Voyant provides a series of options for examining the contexts around a particular word. The first one is a keyword in context (KWIC) interface, Voyant’s representation of one of the most common concordance tools. You can change the word being examined by selecting a new word from the ‘Reader’ pane. By adjusting the context slider, you can modify exactly how much context (i.e., how many words) you see around the instances of the word you are examining. Tools like these can be helpful for interpreting the more quantitative results that the tool provides you. 670 instances of ‘said’ might not mean an awful lot, and the contexts pane can help you to understand how this word is being used. In this case, it can be useful for seeing different conversations: frequently, said followed by a name indicates dialogue from a particular character.

In this list of the first ten uses of ‘said’, two of them are closely joined with a name: ‘Sweeney Todd.’ If we look back at the word cloud for the text, we can see that these two words also occur with high frequency in the text itself. Given this information, we might become interested in a series of related questions:

- How often is Sweeney Todd talking?

- What is he talking about?

- Who is he talking to?

As we move away from particular words towards clusters of phrases in contexts, we also need a new vocabulary to represent those relationships. You may have heard of n-grams from the Google Ngram Viewer, which allows users to search large corpora for specified words or phrases. An n-gram is a sequence of words that occurs next to each other of a particular length: the ‘n’ becomes a stand-in for the specified length of phrase. So take the following sentence:

“This is a sentence to illustrate ngrams.”

“To illustrate” is an n-gram of length two, while “is a sentence” is an n-gram of length three. We use a convenient shorthand for referring to ngrams of this length: bigrams and trigrams.

Collocations are words that tend to occur together in meaningful patterns: so ‘good night’ is a collocation because it is part of a recognized combination of words whose meaning changes when put together. ‘A night,’ on the other hand, is not a collocation because the words do not form a new unit of meaning in the same way. We can think of collocations as bigrams that occur with such frequency that the combination itself is meaningful in some way.

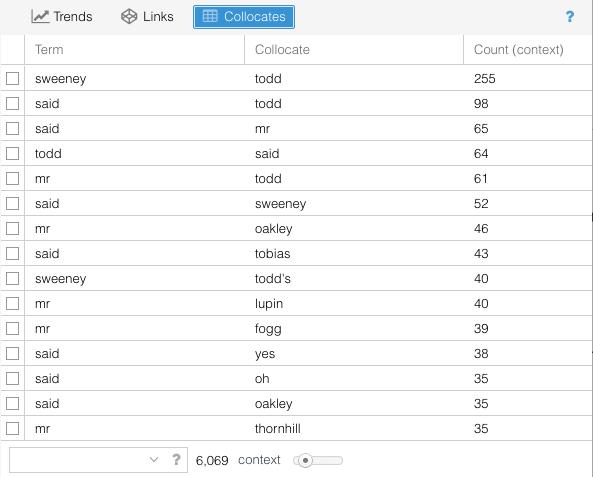

In a similar way, Voyant allows you to see the phrases and words that occur to next to each other in the text on a regular basis. To access the ‘Collocates’ tool, you might need to hover over the question mark in a pane, and select the grid option to add a tool pane. From this menu, select ‘grid tools’ and ‘collocates.’ The ‘context’ slider allows you to find sentences where two words occur near each other. So setting a context of three for ‘sweeney’ and ‘todd’ will give you all the three word phrases in which those two words occur: they do not need to be contiguous. In this case “Sweeney Todd said” would match, as would “Sweeney said Todd.” Each row tells you how often those words appear within a certain distance from each other.

Looking at this data on collocations can lead to interpretive questions you might want to pursue. For one, a lot of the collocations are men’s names (Sweeney Todd, Mr. Oakley, Mr Lupin, Mr. Fogg, etc.), whereas no female characters appear in the list of most frequent collocations. What might that tell you about the nature of the text and the way the author was shaping it to appeal to an intended male audience? Or, consider the very high number of collocations for “Sweeney Todd” – more than twice the next highest collocation. At one level, this isn’t terribly surprising. Sweeney Todd is the main character, after all. At another level, you might find it odd that his name was repeated so frequently in the text: how often did the readers need to be reminded of what his full name was? But maybe this gives you some insight into the nature of the work as a serial novel. If readers were consuming the work in weekly installments over the course of many months (while they were probably reading other serial novels), they may indeed have needed reminders about the main character’s name (as well as other essential plot points). These are all potential avenues of interpretation; to make any of these arguments, you’d need to gather additional evidence – but at least Voyant gives you places to start.

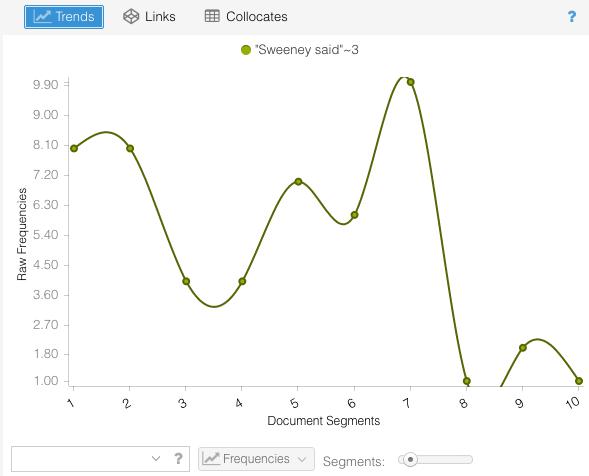

Click on the row that lists ‘said sweeney 52’. Many of the windows in Voyant are interactive, and selecting something will modify the visualizations and options available to you elsewhere in the tool. Selecting a row here will modify a line graph that shares a space with the collocates table. You’ll need to select ‘Trends’ at the top of the pane in order to see the line graph.

When you do, you will see a graph of the selected collocation over time. ‘Sweeny’ and ‘said’ occur within a space of three words in highly variable amounts over the course of the text. By looking at the graph, we can get a rough idea of when Sweeny Todd speaks over the course of the narrative.

To graph things, Voyant breaks up your document into a segments (you can change how many it uses). Within each piece of the text it calculates how often the selected phrase or word appears. In this case, we might say Sweeney Todd talks significantly more in the first 70% of the text than he does in the last portion. Since you read the last few chapters of the novel, you might have a sense of why this is. The end of the text deals primarily with revelations about Todd’s actions than his actions themselves. Of course, you wouldn’t know this if you hadn’t read portions of the text, a good example of how “distant reading” and regular, old-fashioned reading can and should enrich each other.

The ‘trends’ pane can be quite handy, and it will allow you to see individual words or phrases as they rise and fall over the course of a corpus. Think of it as the next step in critically analyzing a concordance. After all, texts occur in sequence, and we can learn a lot from examining the locations in which significant words tend to cluster. You can think of this graph feature as roughly charting the time of the narrative and as helping you think about the order in which words occur.

Thinking about language as it unfolds over time in this way can offer new opportunities for analysis. It can also raise issues. In a single text like The String of Pearls, composed over a relatively brief period of time, we don’t need to worry too much about changes in language. But very often we might be studying loads of texts published over the course of many years, decades, or centuries. We cannot assume that language means the same thing over corpora like these. Words change over time. Your data and interests will determine how important this caveat is for you. Think carefully about whether any significant political, social, or technological events during that time could inflect how language works in the texts you care about. History can enrich your work or deeply complicate it.