Bags of Words

When we read, our eyes move in sequence across the page and take in phrase after phrase in the order in which they were intended. This fact allows us to do interesting things graphing words over time using Voyant. This sense of chronology is integral to how we, as human readers, understand texts. But it is possible to imagine other ways of reading. Have you ever skimmed over a page backwards looking at every other word? You probably still got the gist of the text even though you didn’t read it in order and even though you missed many of the words.

Take this passage:

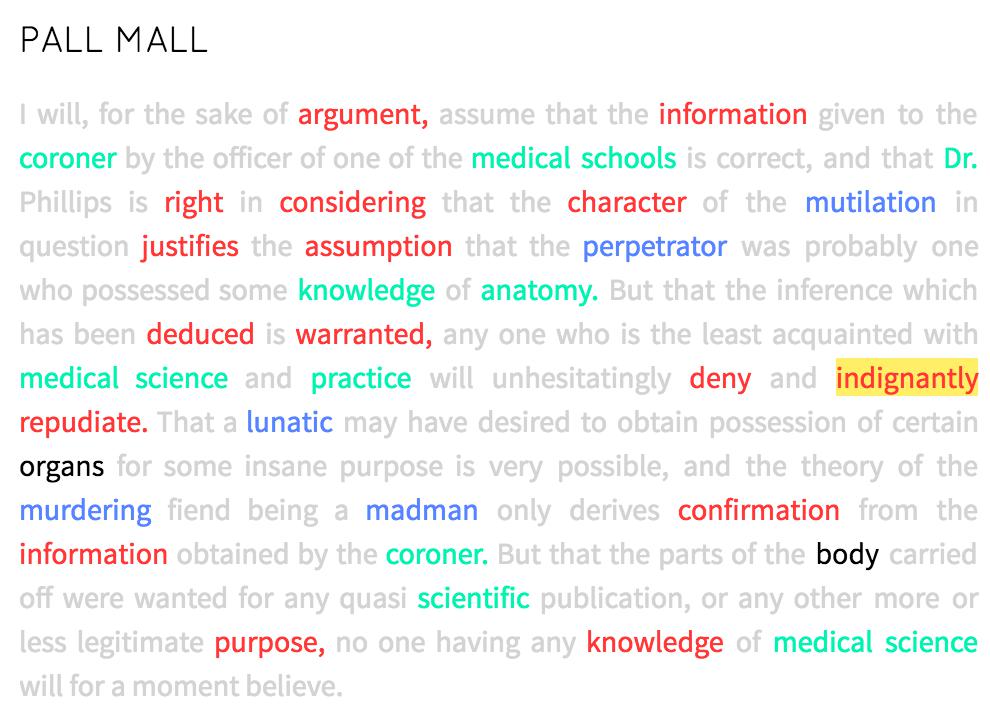

I will, for the sake of argument, assume that the information given to the coroner by the officer of one of the medical schools is correct, and that Dr. Phillips is right in considering that the character of the mutilation in question justifies the assumption that the perpetrator was probably one who possessed some knowledge of anatomy. But that the inference which has been deduced is warranted, any one who is the least acquainted with medical science and practice will unhesitatingly deny and indignantly repudiate. That a lunatic may have desired to obtain possession of certain organs for some insane purpose is very possible, and the theory of the murdering fiend being a madman only derives confirmation from the information obtained by the coroner. But that the parts of the body carried off were wanted for any quasi scientific publication, or any other more or less legitimate purpose, no one having any knowledge of medical science will for a moment believe.

The excerpt is from a letter cited below about the Jack the Ripper murders from the Pall Mall Gazette published on September 28, 1888. Even without knowing anything about the context, you can probably infer a rough sense of the topic of the text: murder. We might further say that there are a number of overlapping topics in the text: evidence, medicine, murder, and many more. But how did you recognize these themes in the paragraph? If you skimmed the text, certain words might have lept out at you as indicating these topics. You see the words “coroner” and “body,” and these words suggest particular things and not others. They make you think, “This article is about crime or medicine.” They do not make you think, “Oh I’m reading a recipe for a nice guacamole” (or at least we really hope they don’t). Vocabulary are the building blocks of the themes in a passage, and we can, theoretically, determine the topics at work in a text by paying close attention to the kinds of words that appear in it. Here is the same passage with one representation of how the reading process for this article might have taken place for you using Prism. We have highlighted various words associated with particular categories as such:

Highlight Color: Topic

---

red: evidence

green: medicine

blue: murder

black: words where two or more topics were marked the same amount.

grey: no topic marked

This is a visual model of how we might read the text. In this example, each of these colors represents a different kind of topic with which the text is dealing. Each topic is made of particular discourses: language associated with proving things, a vocabulary connected to medicine, and a series of words about crime. Other newspaper articles about Jack the Ripper could feature a different set of themes. The subject of the articles could change, the vocabulary would reflect this, and our sense of the underlying topics would shift accordingly. Probably most of these texts deal with crime, but you might have some Jack the Ripper articles that focus on the victims or on the police investigation into the murders.

Take a closer look at the kinds of words that we highlighted in the article above. Certain words might be really good indicators of a particular topic, while others might be fuzzier indicators of what we’re talking about. For instance, although the word ‘practice’ might appear in conversations about both medicine and sports, a word like ‘anatomy’ is more closely and clearly indicative of a scientific topic.

Wouldn’t it be interesting if we could somehow see the whole web of topics that occur in a text? And if we could find out how different topics appear in different texts and the degree to which the discuss them, we could figure out ways to distinguish between texts.

One problem with using Prism to do this work is that it depends on someone setting up these themes or topics beforehand, and thus in essence knowing or guessing something about the text before the text analysis process begins. But maybe there are some “hidden” topics in the text that we don’t even know to look for. So what if we could use computers not just to distinguish between texts based on the topics they discuss, but also to find the very topics themselves?

We are beginning to float a different kind of reading. Let’s take one more step back.

If we take the words in a text as being indicative of its underlying topics, we actually don’t need to worry about word order so much. The sequence of words, sometimes called the syntagmatic axis, only matters for certain kinds of reading. In previous chapters, we have preserved the sense of narrative time in a text - when we counted words with Voyant, we then graphed them over time. We cared about whether and how much a particular phrase occurred in the beginning of the text vs. the end. But we can find out interesting things about texts if we are a little more flexible and think about them not as things that unfold over time but rather as pure token counts, as bags of words. In a bag of words model, word order becomes irrelevant. All we care about is what words occur in a text and how often they do so. Pretty straight forward, right?

Take the following two sentences:

-

“Fine. How are you doing?”

-

“How are you doing? Fine?”

If we normalize a text by removing the stopwords, lowercasing the words, and getting rid of the punctuation, we get a bag of words. In this case, the bag of words for these two sentences is the same:

[

"fine",

"how",

"are",

"you",

"doing"

]

The nuanced context of the sentences that makes the two of them different disappears, but we get the sense that they both discuss similar material. Now, we would not only want to know what words are being used; we’d also want to know how often they are mentioned. So a bag of words model for the following two sentences might produce something like the following:

- Sentence A: “Barbara is doing fine, thank you.”

-

Sentence B: “Thank you, Dave. I am doing fine.”

Words in Corpus [ "Barbara", "is", "doing", "fine", "thank", "you", "Dave, "I", "am" ] Counts for Sentences A: [1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0] B: [0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1]

Here we get two lists. “Words in Corpus” gives all of the words in our documents. “Counts for Sentence A” and “Counts for Sentence B” detail the number of times each of those terms occur in each sentence. So the first element of the Counts list for Sentence A is 1 because “Barbara” occurs 1 time. Sentence B has 0 in that same position because the word “Barbara” does not occur in the sentence. We could have numbers as large as we need in order to represent the text as a whole. Pretty easy for a couple of short sentences, but imagine being able to break apart whole novels like this.

One last thing. Let’s add this sentence to the bag of words model that we’ve been building:

- Sentence C: “I am Dave”

The new model looks like this:

Words in Corpus

[

"Barbara",

"is",

"doing",

"fine",

"thank",

"you",

"Dave,

"I",

"am"

]

Counts for Sentences

A: [1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0]

B: [0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1]

C: [0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1]

Just by glancing at the counts for the three sentences, you could argue that two of the sentences are more similar to each other. Look at how many 1’s you get in the sentences A and B vs. how many 0’s you get in sentence C. You can do a lot of math to prove this, and even start to graph things to visualize the argument. Note that sentences 1 and 3 are mirror images of each other: they don’t share any vocabulary in common. We can think about A and C as opposite ends of a continuum, then, and B being somewhere in between. Since Sentence B shares some with sentence A (both contain “doing,” “fine,” “thank,” and “you”), but more with sentence C (both contain “I” “am” and “Dave,” as well as no “Barbara” or “is” for either one), we can say that sentence B is a bit further to one than the other:

Sentences Graphed by Similarity

A------------------B----------C

For now, don’t worry about the math behind all of this. We just want to give you a sense of the possibilities that can come from considering texts as bags of words. Note that, at a certain point, the vocabulary behind the model becomes irrelevant to this kind of thinking. We’re just working with numbers, which is good for the computer! We can add the meaning and linguistic nuance back at the end, when we use this information to make humanities interpretations.

You might feel like this goes against everything that you’ve ever known about reading. This might feel like destroying a text. You’re not wrong. This concept is pretty far removed from how we tend to read, since we tend to read in sequence across the page. This approach, instead, wants you to think about reading in a different way, to develop a new epistemology for the act. We lose something in the process, the sense of a text as it unfolds over time.

But we also gain the ability to think about a text in new ways. Sentences are just the beginning. You can use a bag of words approach to determine how different or similar whole books or authors are from each other. If we have lists of words for each text as well as for the corpus (or set of documents) as a whole, we can actually work backwards to get a sense of the underlying topics that we were talking about a moment ago. Instead of skimming a paragraph to determine its basic topic, we could scan full texts – and scan lots of them (Brandon’s record is about 1.8 million texts in a corpus). And rather than trying to get a sense of 1-3 topics, we could break our text apart into 15-20 different topics. Now we are cooking with gas, and we’re talking about topic modeling.

Further Resources

- The Wikipedia page on the Bag of Words model was helpful for putting this lesson together.

- While we haven’t quite gotten to topic modeling yet, Matt Jockers has a good summary description of how topic modeling and LDA work in these terms called “LDA Buffet: A Topic Modeling Fable.”

- Daniel Chandler has a helpful explanation of the syntagmatic axis.

- David McClure’s technical post on data mining the HathiTrust corpus with Python pointed us to Chandler’s work.

- Ryder, Stephen P. (Ed.) “THE WHITECHAPEL MURDERSAN EMINENT MEDICAL MAN ON THE CORONER’S THEORY.” Casebook: Jack the Ripper. http://www.casebook.org Accessed: 6 September 2016