Classifying Texts

At this point, you might be saying, “Supervised classification is all well and good, but how does this relate to text analysis? I’m going to go back to googling for animal photos.”

Stop right there! We’ve got one for you. If you think you’re tired, how do you think this dog feels? Impersonating bagels is exhausting.

Now that you’re back and not going anywhere, we should acknowledge that your point is a good one. We wanted to stay relatively simple in the last lesson so that you could get a handle on the basics of supervised classification, but let’s think about the ways you could apply this method to texts. The NLTK book (which you should check out if you want to go into more depth into text analysis) lists some common text classification tasks:

- Deciding whether an email is spam or not.

- Deciding what the topic of a news article is, from a fixed list of topic areas such as “sports,” “technology,” and “politics.”

- Deciding whether a given occurrence of the word bank is used to refer to a river bank, a financial institution, the act of tilting to the side, or the act of depositing something in a financial institution.

Let’s break each of these tasks down. Remember, a supervised classifier relies on labeled data for a training set. This sample data that you’ll be using depends directly on the type of problem you are interested in. You could work backwards, and figure out what kind of training data you would need from the question you are interested in:

- To decide whether an email is spam, you will need lots of examples of junk email.

- To tag a news article as belonging to a particular category, you will need examples of articles from each of those categories.

- To determine the use of the word ‘bank,’ you will need examples of the word used in all these possible contexts.

In each case, it’s not enough to just dump data into the classifier. You would also have to decide what feature sets you want to examine for the training sets for each task. Take the task of building a spam filter. To determine whether or not a text is spam, you would need to decide what features you find to be indicative of junk mail. And you have many options! Here are just a few:

- You might decide that word choice is indicative of spam. An email that reads “Buy now! Click this link to see an urgent message!” is probably junk. So you’d need to break up your representative spam texts into tokenized lists of vocabulary. From there you would work to give the classifier a sense of those words likely to result in unwanted messages.

- You might notice that all your spam notifications come from similar emails. You could train the classifier to identify certain email addresses, pull out those which have known spam addresses, and tag them as spam.

You could certainly come up with other approaches. In any case, you would need to think about a series of questions common to all text analysis projects:

- What is my research question?

- How can my large question be broken down into smaller pieces?

- Which of those can be measured by the computer?

- What kinds of example data do I need for this problem? What kinds do I already have in my possession?

Going through these questions can be difficult at first, but, with practice, you will be able to separate feasible digital humanities questions from those that are impossible to answer. You will start to gain a sense of what could be measured and analyzed as well as figure out whether or not you might want to do so at all. You will also start to get a sense of what kind of projects are interesting and worth pursuing.

Now, let’s practice on a supervised approach to a common problem in text analysis: authorship attribution. Sometimes texts come down to us with no authors at all attributed to them, and we might want to know who wrote them. Or maybe a single text might be written under a pseudonym, but you might have a good guess as to whom might be the author. You could approach this problem in a variety of unsupervised ways, graphing the similarity or difference of particular authors based on a number of algorithms. But if you have a pretty good guess as to whom the author of a particular text might be, you can take a supervised approach to the problem. To step through our same list of steps:

- What is my research question?

- We want to be able to identify the unknown author of a text.

- How can my large question be broken down into smaller pieces?

- We have a reasonable guess as to some possible authors, so we can use those as objects of study. We also are assuming that authorship can be associated with style.

- Which of those can the computer measure?

- Well, style is the sum total of vocabulary, punctuation, and rhetorical patterns, among other things. Those can all be counted!

- What kind of example data do we have that we can for this problem?

- We have the unknown text. And we also have several texts by my potential authors that we can compare against it.

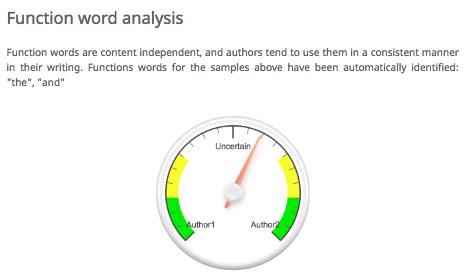

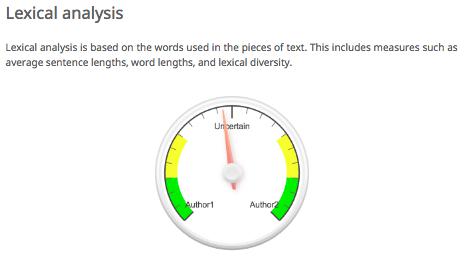

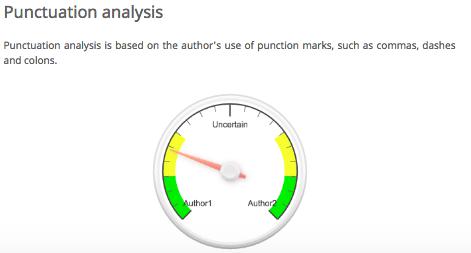

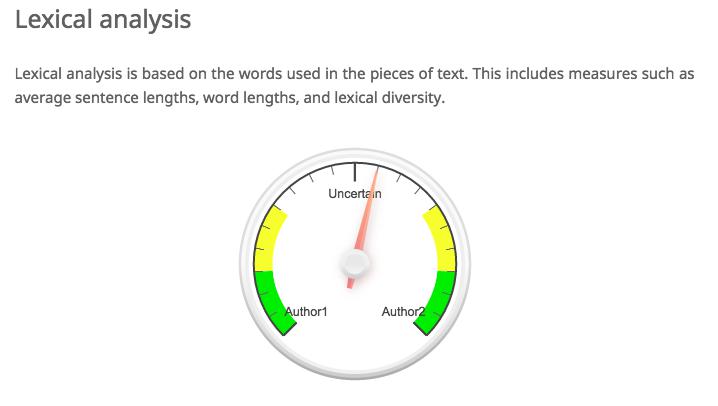

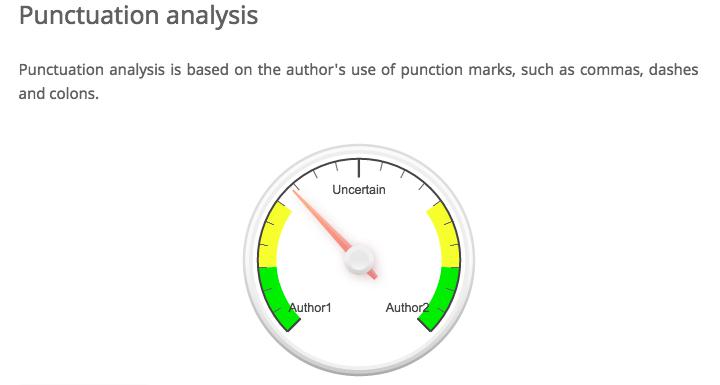

To illustrate this experiment, we took two authors from our syllabus: Danielle Bowler and Pia Glenn. Using their author pages on Eyewitness News and xoJane, we gathered articles that belonged to each. Bowler tends to write shorter pieces than Glenn, so our training set included about double the number of pieces by Bowler (10) as by Glenn (5). With this body of training data for each author, we uploaded the texts to a great online authorship attribution tool by AICBT. The tool allows you to upload sample data for two authors. With this set, you can then upload a text by an unknown author, and the software will try to guess who wrote it based on a variety of text analysis protocols. In this case, the mystery text was “Freedom, Justice, and John Legend” by Bowler. Author 1 is Glenn, and Author 2 is Bowler. The tool attempted to identify the author of the mystery text as follows. The images also include AICBT’s helpful explanation of the different metrics that they are using to analyze the unknown text.

This text is actually by author 2, so for the classifier to be accurate according to these measures, the arrow should point towards the right. You’ll immediately see that we have some success, but also one failure! Function word analysis is a slight indicator of the correct author, lexical analysis is virtually useless, and punctuation analysis is way wrong. In a real classification project, we would want to use the success or failure of our classifier to revise our sense of which features are useful for our particular project. In this case, punctuation is not a good measure at all, so we would throw that out. Instead, we might focus on function words as an indicator of authorship. We can tweak our approach accordingly. But measures like these are only ever working probabilistically. We can say that the mystery text might be written by our second author, but only in rare cases could we ever know for certain.

Note also how these measures of authorship overlap with other things we have studied in this book. Remember stopwords, those words that are so common in a text that they are frequently removed before text analysis? In cases like this one, we actually care a lot about these simple terms. Two of the three measures for authorship here deal with just those words that we might otherwise throw away: punctuation, articles, etc. These words might not tell you much about the subject of a text, but they can tell you an awful lot about how a text discusses them.

Take a text that we’ve talked a lot about in this course: The String of Pearls. This penny dreadful was published in weekly installments and was written (we think) by James Malcolm Rymer and Thomas Peckett Prest. But the work was published anonymously, so we don’t know which author wrote which chapter (or even if Rymer and Prest wrote the novel).

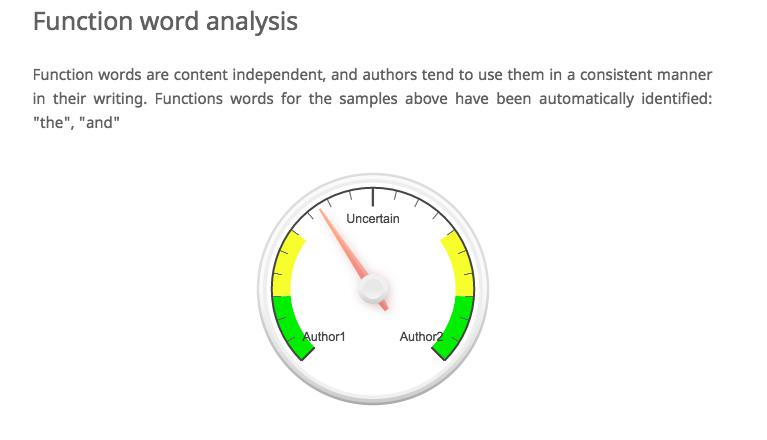

For the purposes of this demonstration, let’s assume that we know that Rymer wrote Chapter One and Prest wrote Chapter Two. So who wrote Chapter Thirty-Three? If we go back to our author attribution tool and copy Chapter One into the box for Author 1 and Chapter Two into the box for Author 2, here’s what we get for Chapter Thirty-Three:

Here, it looks like the tool is trending towards Rymer as the author of the chapter, but we’re mainly dealing with uncertainty. But that uncertainty itself is pretty interesting! Maybe what this is showing us is that the authors had a pretty similar style. Or maybe both authors had a hand in each chapter, and our training set is not particularly useful. If we had large bodies of text by each author we might have better luck. We might want to drill down further and investigate the uses of puncutation in different chapters or the lexical diversity, word length, and sentence length in much more detail.

-

Are other penny dreadfuls similar to The String of Pearls in these respects?

-

If so, what differentiates the style of these works from other types of serial novels?

Similar processes have been used for a variety of authorship attribution cases. The most famous one in recent times is probably that of Robert Galbraith, who came out with The Cuckoo’s Calling in 2013. Using a similar process of measuring linguistic similarity, Patrick Juola was able to test a hypothesis that J.K. Rowling had released the detective novel under a pseudonym. You can read more about the process here.

If we can measure it, we can test it. And you would be surprised at just how many humanities-based research questions we can measure. Taking complicated human concepts like authorship and breaking them down into quantifiable pieces is part of the fun. It is also what makes the process intellectually interesting. If it were easy, it would be boring.

We have just barely scratched the surface of the field of stylometry, or the study of linguistic style using a variety of statistical metrics. You can carry this research process using a variety of programming languages, so you might take a look at our concluding chapter on Where to Go Next if you are interested in learning how to implement these sorts of experiments yourself.