Topic Modeling Case Study

In the previous section, we described how a single text could be broken up into a list of words and their frequencies, and we also suggested that a single text might be composed of any number of discourses or topics. Given enough time and energy, we can imagine a tool that would infer these topics for us without us having to read all of our documents first. The approach that we will take is a technique called topic modeling, a computational method that allows you to discover the topics that construct a text. Topic modeling does so by exercising a variety of statistical protocols over and over again on a text. Executing topic modeling projects yourself takes more hands-on programming than we want to introduce in this coursebook. So instead of exercising the techniques themselves or offering a tool for doing so, we are going to attempt to describe what topic modeling is and how to interpret results from it using a case study. Come talk to either of us in person if you want to go further and explore topic modeling on your own.

We will do a lot of statistical hand-waving in what follows, but we have some extra resources at the bottom of the page if you are interested in learning more about the mechanics of how topic modeling works. In the previous Bags of Words lesson, we walked through a paragraph and suggested that by skimming it you could infer the types of topics that it discussed. Topic modeling works in a similar way: the software looks for words that tend to occur next to each in statistically significant ways. The sum total of these words that occur next to each other becomes legible to a reader as a topic. The previous lesson looked at a single paragraph to think about the kinds of topics it might contain. You can imagine how this would get complicated very quickly when working beyond such a small scale. As humans, we have an upper limit to how much we can hold in our head: we can only keep a few topics in our brains at a time, a few texts in our thoughts. A computer doesn’t have that same problem. Topic modeling software can process hundreds of thousands of texts, over and over again, refining its sense of how all the pieces fit together. It can give us a sense of the themes and discourses that run beneath an entire corpus.

So when you run topic modeling software, it looks for words that occur near each other in texts in meaningful ways over the course of the corpus. In most cases, it looks for words that occur in documents together. Remember, these words are not dependent on their location within the document. Topic modeling works on a bag of words model that only cares about whether or not the words occur within the text, not their position within it. But you might occassionally chunk larger documents into a series of paragraphs so that the software thinks about them each as separate documents for finer granularity. There are a number of similar tricks for refining your processes

After topic modeling a whole corpus, depending on the software you use, you will often be given a lot of information that can be hard to parse. All of these add up to the results of your project. The first important piece, a topic/term matrix, will contain lines that look something like this:

0 2.5 librivox httpupload mp orgshareupload duration mb het de heres van ik size een je en dat te bart voor

1 2.5 file volume audacity problem db files upload edit fix version check dont track click change bit open id computer

2 2.5 text word read words dont make question change made pronunciation didnt point names doesnt understand makes sense long sentence

5 2.5 recording project end librivox post files file number thread section read link completed sections title book complete seconds silence

7 2.5 english years life world language history people american school accent books german french work interesting literature live book written

8 2.5 project page catalog httplibrivox found files link archive audio complete added add cover list links readers google put site

The program spits out a series of “topics,” which in this case are defined as sets of words that tend to occur in documents together with statistical significance. In these examples, we asked for the program to give us twenty topics; the identifying number of each topic is the first number on the left side. Note two things. First, the numbers start with 0 and end with 19, instead of starting with 1 and ending with 20. Second, we have selected a few topics to highlight out of the total number; not all twenty are listed here. After the numbers, you see the series of words that make up that topic. The computer does not know anything about these topics at all; it merely sees that these words often co-occur in documents.

The real work of topic modeling involves interpreting these topics in ways to make them meaningful to readers. Some of them are noise, artifacts of words that tend to occur next to each other. But others make more sense. Based on topics 1 and 5 you might be able to infer that these particular texts came from descriptions of sound recordings of some kind. Topic 2 might suggest that we are talking about reading texts. Much of the work of topic modeling involves trying to make assumptions about what kinds of discourses these clusters of words imply. In this case, the corpus under question is about 1.8 million forum posts from librivox.org, a site that produces public domain audiobooks. All of the examples in this lesson are drawn from work that Brandon has done examining these materials. Some more topics:

11 2.5 recording librivox post test find make start wanted record forum minute thread fun check link listeners things readers give

12 2.5 noise sound recording good bit sounds hear mic voice background microphone record volume silence editing quality loud dont recordings

13 2.5 part read act line parts missing lines play great wrotei id editing role character narrator todd put dramatic edit

14 2.5 section pl mw sections ready uploaded notes fixed corrected updated maryann repeat betty wrotehi wrotesection spot reuploaded pling phil

15 2.5 de la le je les pour pas en vous ne est si ce dans du des merci il mais

17 2.5 ich die und der ist das du von es nicht den auch ein im noch zu wenn kapitel aber

19 2.5 reading read great book listening books reader listen love recordings enjoy forward wonderful listened proof job voice work enjoyed

Looking at these topics, we might see that a number of them deal with aspects of sound recording. In particular, the texts often tend to talk about the act of producing these recordings. This makes sense, as users of LibriVox actually create and upload recordings themselves. Topics 15 and 17 are also notable, as they represent French and German language topics. In any large corpus that is primarily one language, texts written in other languages will tend to group together. If we assumed before that medical language would tend to occur next to each other, this makes sense. French vocabulary is far more likely to appear next to other French vocabulary, in a text that is entirely French, relative to a larger corpus that is primarily in English.

For each document in the corpus, topic modeling also spits out a matrix showing what percentage each topic is likely to contribute to that text. The matrix might contain hundreds of thousands of segments that look something like this (modified slightly for readability):

0 httpsforum.librivox.orgviewtopic.phpf23t2

12 0.14788732394366197

1 0.13380281690140844

11 0.07746478873239436

2 0.06338028169014084

19 0.04929577464788732

18 0.035211267605633804

17 0.035211267605633804

16 0.035211267605633804

15 0.035211267605633804

14 0.035211267605633804

13 0.035211267605633804

10 0.035211267605633804

9 0.035211267605633804

8 0.035211267605633804

7 0.035211267605633804

6 0.035211267605633804

5 0.035211267605633804

4 0.035211267605633804

3 0.035211267605633804

0 0.035211267605633804

The first line here contains information about the document, an ID for the document and then a name for it. In this case, each forum post has its own URL, so we are using the URL for the ID:

0 httpsforum.librivox.orgviewtopic.phpf23t2

This post is post number 0, the first post chronicled by the topic modeling software. Brandon stripped out some of the punctuation, but you probably recognize what follows as looking sort of like a URL. This topic modeling information corresponds to a forum post that exists at this URL: https://forum.librivox.org/viewtopic.php?f=23&t=2. What follows is a list of each topic our topic modeling software produced and the weight of each topic for that document:

12 0.14788732394366197

1 0.13380281690140844

11 0.07746478873239436

17 0.035211267605633804

15 0.035211267605633804

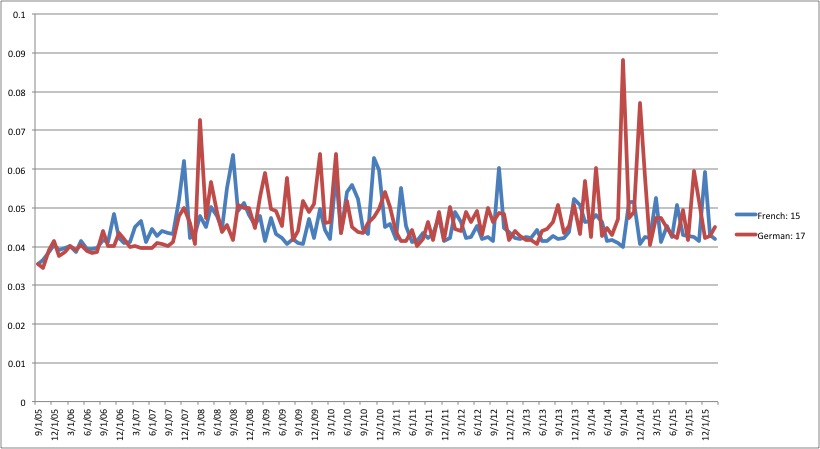

So topics 12, 1, and 11, in that order, are the three most prominent topics in the document. Topic 12 has a weight of 14% in the document, and so on. Topic 12 is far more likely to appear in this document than topics 17 and 15. Using this information, if we know the dates that each text was published, we can actually determine the rise and fall in prominence of different topics over time (see the Further Resources on this page for cautions when doing so). We could see how discourse ebbs and flows over the course of our corpus. Remember topics 15 and 17, our German and French language topics? They aren’t especially prominent in this first text, which makes sense because it was written in English. There is a pretty low likelihood that German or French words are going to show up in an otherwise English text, all things considered. But we can use this information to get a sense of where French and German texts are likely to occur by charting the ebb and flow of the French and German topics over time:

We get clear spikes in the German topic from September to December 2014, and slightly smaller peaks in the French topic in late 2007 and 2008. Since we know that these topics represent pretty coherent approximations of the use of French and German language in the corpus, we can use techniques like these to argue that these particular moments represent periods of heightened activity by the French and German communities of LibriVox users. Based on this evidence, we could make arguments about the global interconnectedness of the community of LibriVox users. We might then take this information back to the corpus and ask new questions based on this data.

-

What kinds of books are important to these communities?

-

What kinds of conversations are they having?

-

Why do these languages spike at these particular times?

Until now, we have stressed approaching text analysis with a clear sense of your interests and the research questions that drive them. Topic modeling works a little differently: it is more useful for exploratory work. We call topic modeling unsupervised classification because we are asking the computer to analyze and mark a text without giving it any clear directions. We just say, “here is some text. Do your thing and tell me what you find.” A supervised classifier would take information from us to help it make decisions. We might say, “read this text. If it has more than fifty uses of the word ‘crime’ mark it as ‘detective fiction.’ If it has fifty uses of the word ‘love,’ mark it as ‘romance’” (more on supervised classifieres in the next chapter). Unsupervised classifiers like topic modeling instead know very little about the underlying texts that they are examining. Instead, they process them based on an underlying model.

In the last lesson we called the bag of words model an epistemology of texts, a way of understanding documents that might be different from what you were familiar with. In the case of the kind of topic modeling we have been discussing, that model could further be called Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA). We won’t go into any detail about the specifics of LDA, but it is important to know that this is the model you are working with and that LDA assumes that a text is constructed from a small number of topics.

Don’t be alarmed if topic modeling seems much more abstract than the material we have covered until now. To really understand how topic modeling works under the hood, you will need to have a grasp of a variety of different topics in machine learning and statistics. We are not so concerned that you understand these specifics. We care, instead, that you understand the idea behind it, have some sense of how to read make sense of other topic modeling projects, and be able to explain them to others in general terms.

Further Resources

-

Andrew Goldstone and Ted Underwood have a great case study of topic modeling PMLA that also includes lots of useful introductions to topic modeling.

-

The Programming Historian has a good introduction for executing topic modeling yourself using Mallet. It gets technical, but the early surveys of what topic modeling is can be very helpful.

-

For a more thorough explanation of how the algorithm behind topic modeling works, you might take a look at Lisa Rhody’s class exercise for teaching LDA.

-

Miriam Posner is helpful on understanding topic modeling results.

-

Benjamin Schmidt in “Words Alone: Dismantling Topic Modeling in the Humanities” provides very useful cautions when working with topic models over time.