Remixing the Sound Archive: Cut-up Poetry Recordings

16 Jun 2017 Posted in:digital humanities talks audio [Recently I spoke at NEMLA 2017 with Ken Sherwood and Chris Mustazza. The panel was on “Pedagogy and Poetry Audio: DH Approaches to Teaching Recorded Poetry/Archives,” and my own contribution extended some past experiments with using deformance as a mode of analysis for audio recordings. The talk was given from notes, but the following is a rough recreation of what took place.]

Robust public sound archives have made a wide variety of material accessible to students and researchers for the first time, and they provide helpful records of the history of poetic performance throughout the past century. But they can also appear overwhelming in their magnitude, particularly for students: where to begin listening? How to begin analyzing any recording, let alone multiple recordings in relation to each other? This talk argues that we can help students start to explore these archives if we think about them as more than just an account of past performances: sound collections can provide the materials for resonant experiments in audio composition. I want to think about new ways to explore these archives through automatic means, through the use of software that algorithmically explores the sound collection as an object of study by tampering with it, dismantling it, and reassembling it. In the process, we might just uncover new interpretive dimensions.

This talk thus models an approach to poetry recordings founded in the deformance theories of Jerome McGann and Lisa Samuels and the cut-up techniques of the Dadaists. I prototype a pair of class assignments that ask students to slice up audio recordings of a particular poet, reassemble them into their own compositions, and reflect on the process. These acts of playful destruction and reconstruction help students think about poems as constructed sound objects and about poets as sound artists. By diving deeply into the extant record for a particular poet, students might produce performative audio essays that enact a reading of that artist’s sonic patterns. By treating sound archives as the raw ingredients for poetic remixes, we can explore and remake sound objects while also gaining new critical insight into performance practices. In the process of remixing the sound archive, we can encourage students to engage more fully with it. And while I frame this in terms of student work and pedagogy given the topic of the panel, it should become clear that I think of this as a useful research practice in its own right.

I will frame the interventions and theoretical frameworks I am making before proposing two different models for how to approach such an assignment depending on the instructor’s own technical ability and pedagogical goals: one model that uses Audacity and another that uses Python to cut and reassemble poetry recordings. I will demonstrate example compositions from the latter. It will get weird.

There are two provocations at the center of my talk founded in an assumption about the way students hear poetry recordings. In my experience, they often hear recordings not as sound artifacts but as representations of text. They might come to these recordings looking to hear the poet herself speak, or they might be looking to get new perspectives on the poem. But they fundamentally are interested in hearing a new version of a printed text, in hearing these things as analogues to print. This is all well and good - the connection to a text is clearly a part of what makes poetry recordings special, but I think our challenge as teachers and thinkers of poetry is to help students surface the sounded quality of the artifacts, to learn to dig deeper into digital sound in particular.

My approach to this need - the need to get students to look beyond the text and towards the sound - is to get them working with these materials as heard objects. We are going to engage them in the medium. They are going to get their hands dirty. We are going to take sound - which might seem abstract and amorphous - and make it something they can touch, take apart, and reassemble. They are going to think about sound as something concrete and constructed by engaging in that very act of construction.

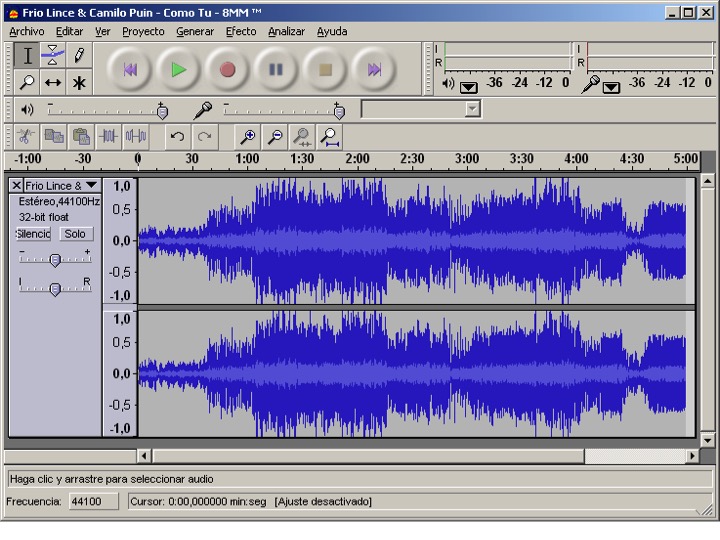

One approach to this might be to use a tool like Audacity. If you’re not familiar, Audacity is an open source tool that lets you input sound clips and then edit them in a pared down interface. If you have an MP3 on your computer, right click it to open it in Audacity, and you will get something like this:

A waveform. Already we are a bit alienated from the text because this visualization doesn not really allow you to access the text of the poem as such. Interacting with the poem becomes akin to touching a visual representation of sound waves. Now, you can’t do everything in Audacity, and that’s what I like about it. When I was a music student in college I remember getting introduced to some pretty beefy sound software - Pro Tools and Digital Performer. I also remember feeling pretty overwhelmed by what they had to offer. So many options! Hundreds and thousands of things to click on! What I like about Audacity is that it is a bit more stripped down. Instead of giving you all the potential options for working with sound, it does a smaller subset really well. Record, edit, mix, etc. Audacity is also open source, so it is free while the other ones are quite expensive.

I would suggest having your students engage with recordings using this software. Here is an example assignment you might put together that asks them to put together an audio essay. Using Audacity, I would have them assemble their own sound recording that mixes in examples from other poetry recordings under examination. You might frame the exercise by having them work through a tutorial on editing audio with audacity that I put together for The Programming Historian. The Programming Historian provides tutorials for a variety of digital humanities tools and methods, so this piece on Audacity is meant for absolute beginners. It coaches people through working with the interface, and, over the course of the lesson, readers produce a small podcast.

The lesson asks readers to use a stub Bach recording, but I would adapt it to have students assemble an essay that analyzes a poetic sound recording relevant to the course material. Instead of writing a paper on a recording, the students actually integrate their audible evidence into a new sound object, assembling the podcast by hand. Citation and description can join together in this model, and I can imagine having a student pay close attention to the audible qualities of the sounds they are discussing. The sky is the limit, but, personally, I like to imagine students analyzing TS Eliot’s voice by mimicking his style. Or you could imagine an analysis of his accent that tries to position his sense of locality, nation, and the globe by examining clips from a number of his recordings alongside clips of other speakers from around the world.

I see several benefits to having students work in this way. Students could learn a lot about Audacity producing these kinds of audio essays, and anyone planning to work with audio in the future should possess some experience with this fundamental tool. The wealth of resources for Audacity mean that it is well-suited for beginners. There are far more substantial tutorials for the software besides my own, so students would be well supported to take on this reasonably intuitive interface.

But there are also limitations here. For one, this type of engagement is a really slow process. Your students, after all, are engaging with a medium that they can only really experience in time. If you are working with four hours of recordings, you really have to have listened to all or most of that sound to work with it in a meaningful way. And to make anything useful, they will probably want to have listened to it multiple times and have made some notes. That is an extraordinary amount of time and energy, and we might be able to do better.

In addition, the assembling process is deliberate. You are asking students to put together clips bit by bit in accordance with a particular reading. And this is the real problem that I want to address - the medium here is unlikely to show you anything new. It is meant to illustrate a reading you already have. You want to produce an interpretation, so you illustrate it with sound. The theory comes first - the praxis second.

So I want to ask: what are some other ways we can work with audio that might show us truly new things? And how can we get around the need to listen slowly? The work by Tanya Clement and HiPSTAS offer compelling examples for distant listening and audio machine learning as answers to these questions. I want to offer an approach based on creativity and play. By embracing chance-based composition techniques at scale, we can start to develop more useful classroom assignments for audio.

In shifting the interpretative dimensions in this way, I am drawing on an idea that comes from Jerome McGann and Lisa Samuels: deformance. At the heart of their essay on “Deformance and Interpretation” is a quote from Emily Dickinson:

“Did you ever read one of her Poems backward, because the plunge from the front overturned you? I sometimes (often have, many times) have — a Something overtakes the Mind –”

McGann and Samuels take her very literally, and they proceed to model how reading a poem backwards, line by line, can offer generative readings. This process illustrated two main ideas. The first was that reading destructively and deformatively in this way exposes new parts of the poetry that you might not otherwise notice. You get a renewed sense of the constructedness of a poem, and the materiality of it rises to the surface. By reshaping, warping, or demolishing a poem, you actually learned something about its material components and, thus, the original poem itself. The second idea was that all acts of interpretation remade their objects of study in this way. By interpreting, the poem and our sense of it changed. So destructive reading performs this process in the fullest sense by enacting an interpretation that literally changes the shape or nature of the object. For a fuller history and more satisfying explanation of the interpretive dimensions of audio deformance for research, check out “Vocal Deformance and Performative Speech, or In Different Voices!” posted by Marit J. MacArthurt and Lee M. Miller over at Sounding Out. They also work with T.S. Eliot, though they they are working with recordings by him rather than those done by amateur readers.

In thinking about this performative form of reading, I was struck at how similar it sounded to cut-up poetry, the practice of slicing apart and rearranging the text of a poem so as to create new materials as popularized by the Dadaists and William S. Burroughs. To make the link to the Audacity assignments I was discussing earlier, I became interested in how this kind of performative, random, and destructive form of reading might extend the experiments in listening that I discussed with Audacity. Rather than having students purposefully rearrange a sound recording themselves, perhaps we could release our control over the audio artifact. We would still engage students in the texture of the medium, but we would ask them to let their analysis and their manifestation of that thinking grow a little closer together. We would invite play and the unknown into the process.

So we will ask them to engage in the material aspects of poetry by interacting with it as a physical, constructed thing. But the engagement will be different. We will have them engage. We will have them warp. We will have them cut up. Rather than using scissors, we will let a computer program do the slicing for us. The algorithm that goes into that program will offer our interpretive intervention, and we will surrender control over it just a bit, with the understanding that doing so will offer up new interpretive dimensions later on.

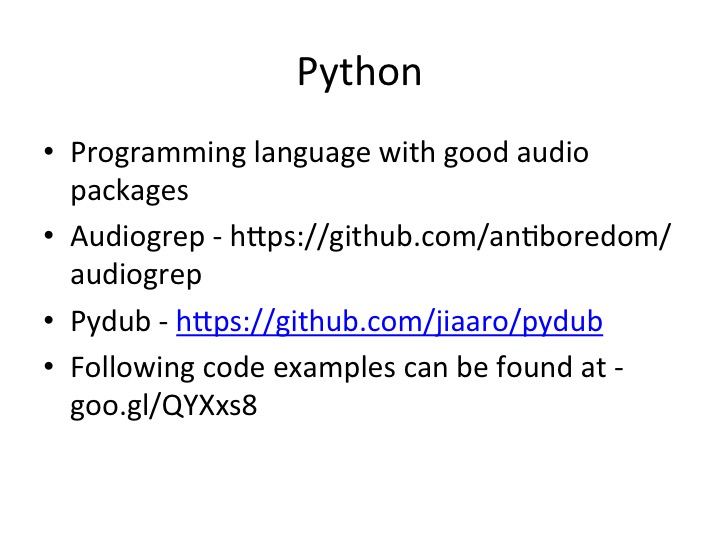

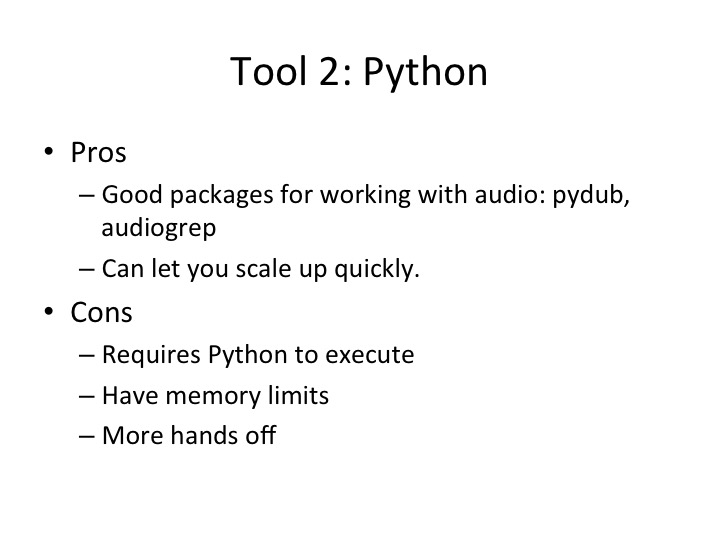

My approach to this was to use computer programs written in Python - a tool that allowed ways around some of the limitations that I already noted for working with Audacity. By working with a computer program I was able to produce something that could read hours of audio far quicker than I could. Python also allowed me to repurpose extant audio software packages to manipulate the audio according to my own algorithms/interpretations. In this case, I was working with Audiogrep and Pydub. I did not need to reinvent the wheel, as I could let these packages do the heavy lifting for me. In fact, a lot of what I did here was just manipulate the extant documentation and code examples for the tools in ways that felt intellectually satisfying. The programming became an interpretive intervention in its own right that, as I will show, brought with it all sorts of serendipitous problems. All the code I used is available as a gist – it took some tinkering to get running, and it will not run for you out of the box without some manipulation. So feel free to get in touch if you wanted to try these things yourself. I can offer lessons learned!

In working with these tools, it quickly became clear that I needed to spend time exploring their possibilities, playing with to see what I could do. In that spirit, I will do something a bit different for the remainder of this piece. Rather than give an assignment example up front, I will share some of the things you can do to audio with Python and why they might be meaningful from an interpretive standpoint. Then I will offer reflections at the end. My workflow was as follows:

- I assembled a small corpus of sound artifacts – in this case, all the recordings of The Waste Land recorded by amateur readers on LibriVox.

- I installed and configured the packages to get my Python scripts running.

- Then I started playing, exploring all the options these Python packages had.

The first step of this process involves having the script read in all the recordings so that they can be transcribed. To do so, Audiogrep calls another piece of software called Pocketsphinx behind the scenes. The resulting transcriptions look like this:

if it is a litter box recording

<s> 4.570 4.590 0.999800

if 4.600 4.810 0.489886

it 4.820 4.870 0.127322

is 4.880 4.960 0.662690

a 4.970 5.000 0.372315

litter 5.010 5.340 0.939406

box 5.350 5.740 0.992825

recording(2) 5.750 6.360 0.551414

The results show us that audio transcription, obviously, is a vexed process, just as OCR is a troubled way of interacting with print text. What you see here is a segment from the transcription along with a series of words that the program thinks it heard. In this case, the actual audio “This is a librivox recording” becomes heard by the computer as “If it is a litter box recording” Although my cat might be proud, this shows pretty clearly that the process of working algorithmically is inaccurate. In this case, listening with Python exposes what Ryan Cordell or Matthew Kirschenbaum might describe as the traces that the digital methods leave on the artifacts as we work with them. Here is the longer excerpt of the Audiogrep transcription for this particular recording of The Wasteland:

the wasteland

i t. s. eliot

if it is a litter box recording

oliver box recordings are in the public domain

for more information or to volunteer

these visits litter box dot org

according my elizabeth client

the wasteland

i t. s. eliot

section one

ariel of the dead

april is the cruelest month

reading lie lacks out of the dead land mixing memory and designer

staring down roots with spring rain

winter kept us warm

having earth and forgetful snow

feeding a little life with tribes two birds

Lots of problems here. We could say that to listen algorithmically is to do entwine signal with noise, and, personally, I think this is great! From an interpretive standpoint, this exposes artifacts from the remaking process and shows how each intervention in the text remakes it. In a deformance theory of interpretation, you cannot work with a text without changing it, and the same is true of audio. In this case, the object literally transforms. Also note that multiple recordings will be transcribed differently. Every attempt to read the text through Python produces a new text, right in line with the performative interpretations that McGann and Samuels describe. Regional accents would produce new and different texts depending on the program’s ability to map them onto recognized words.

But you can do much more than just transcribe things with Python. When this package transcribes words, it tags each of the words with a timestamp. So you can disassemble and reassemble the text at will, using these timestamps as hooks for guiding the program. Rather than painstakingly assembling readings by hand, you could search across the recording in the same way that you might a text file. Here is an example of what you can do with one of Audiogrep’s baked in functions - you can create supercuts of a single word or cluster of related words:

Sam Lavigne has other examples of similar audio mashups on his site describing what you can do with Audiogrep. In this case, I’ve searched across all the recordings for instances of “sound” and “voice” and mashed up all those instances. You can also use regular expressions to search, allowing for pretty complicated ways of navigating a recording. Keep in mind that this is only searching across the transcriptions, which we already noted were inaccurate. So it is proper to say that this method is not telling you something about the text so much as about the recordings themselves. The program is producing a performative reading of what it understands the texts behind the audio to be. The script allows you to compare multiple recordings in a particular way that would be pretty painstaking to do by hand, but the process is imperfect and prone to error. Still, I find this to be a useful tool for collating the intonations and cadences of different readers. I am particularly interested in how amateur readers perform and re-perform the text in their own unique ways. This method allows me to ask, for example, whether all readers sonically interpret a particular line in the same or different ways.

You can also have the program create your own, new sound artifacts drawing upon the elements of the originals. Since we have all the transcriptions, we can also create performative readings of our own. Rather than getting all instances of one word, we can put together a new text and have it spoken through the individual sound clips drawn from our input. Before playing the result, read through what I wrote.

Approaching sound in this way is a way for our students to reconstitute their own ideas through the very sound artifacts that they are studying. In so doing, they learn to consider them as sound, as material objects that can be turned over, re-examined, disrupted, and reassembled. But look at how much is gone. How much gets lost. The recording is notable for its absences, its gaps.

That should give you a hint about what kind of recording is about to come out. What follows is the program’s best attempt to recreate my passage using only words spoken by LibriVox readers as they perform Eliot’s text.

The recording itself performs the idea, which is that working in Python in this way produces a reading that is somewhat out of control of the user. You cannot really account ahead of time for what will be warped and misshaped, but some distortion is inevitable. By passing the program the passage, it will search through for instances of each word and try to reassemble them into a whole. The reading becomes the recording. But we are asking the computer to do something when it does not have all the elements it needs to complete the task - we have asked it build a house, but we have given it no material for doors or windows. The result is a garbled mess, but you can still make out a few words here and there that are familiar. We hear a few things that are recognizable, but we also get a lot of silences and noise, what we might think of as the frictions produced by the gaps between what the script recognizes correctly and what it does not. The result is sound art as much as sound interpretation.

One last one. This one is a bit frightening.

While trying to mash up all the silences in the recording to get a supercut of people breathing, I made a conversion error. Because of my mistake, I accidentally dropped a millisecond every five or six milliseconds in the recording rather than dropping only the pieces of spoken word. From this I learned how to make any recording sound like a demon. I think moments of serendipity like this are crucial, because they expose the recording as a recording. This effect almost sounds analogous to the sort of artifacts that might get accidentally created in the recording process. The process of approaching the recording leaves nothing unchanged, but, if we are mindful of these transformations, we can use them in the service of discovery.

So, to review: you can use Python to create supercuts of particular words, to perform readings of a text, to expose artifacts from the recording and transcription process, or to create demons. So my assignment for python might go something like this.

Take some recordings and play around. I think you get the most out of a research method like this by letting the praxis generate the theory. Then let the outcomes reflect and revise the theory. Your students can serendipitously learn new things from these sorts of experiments, even if they might seem silly. Instead of shying away from the failures involved in transforming sound recordings into transcriptions and back again, I propose that we instead take a Joycean approach that “errors are volitional and are the portals of discovery.” The exercise could ask you to consider the traces of digital remediation that are present in the artifacts themselves. Or, it could generate a discussion of regionalism and accents of the Librivox participants that threw the transcriber off. To go further (on the excellent question/suggestion of a NEMLA audience member), this process could expose the fact that, in transcribing audio, the program favors particular pronunciations and silences those voices who do not accord with its linguistic sense of “proper” English. You might get a new sense of the particular vocabulary of recorded words in a text, and what it leaves out. Or you might get a renewed sense of how interpretation is a two-way street that changes our texts as we take them in.

So Python offers some robust ways of working with audio through some packages that are ready to go. This lets you scale up quickly and try new things, but it is worth noting that these methods require far more technical overhead than using Audacity. For this reason, I mentioned training wheels above. Depending on your course, it might be too much to ask students to program in Python from scratch for an assignment like this. So you might offer them starter functions or detailed guides so they do not need to implement the whole thing themselves. The hands-off approach here might be more than some instructors or researchers are willing to allow. Furthermore, while I do think these methods are appropriate for scaling up an examination of audio recordings to compare many different audio artifacts, there are important limitations in the Python audio packages that, without significant tinkering, limit the size of the audio corpus you can work with.

For me, though, the possibilities of these approaches are generative enough to work around these limitations. Methods like these are useful for exposing students to sound archives as more than just pieces of cultural history but also as materials to be used, re-used, and remixed into their own work. I have deliberately chosen as my examples here only recordings of texts as given by amateur readers to suggest that these materials have always been performed and re-preformed. The assignments above ask students to place themselves in this tradition of recreation, and the approach invites them to view these interventions with a sense of exploration and humor.