Collation and Writing Pedagogy

17 Jan 2015 Posted in:pedagogy talks conferences [The following is the talk that I gave at the 2015 MLA Conference on a panel on “Pedagogy and Digital Editions.” The Google Docs section is a slight reworking and recontextualization of a previous post on the subject. I’m especially grateful to Sarah Storti and Andrew Stauffer for their suggestions and comments on how to use Juxta Commons to teach writing. A version of this piece was selected for publication in Digital Pedagogy in the Humanities under their “Text Analysis” keyword.]

Collation and Writing Pedagogy with Juxta Commons and Google Docs

We typically think about using digital collation to compare those documents that already exist. The usual model gathers multiple copies, multiple witnesses, of the same text, and juxtaposes them to gather a sense of the very small, micro changes that have been made to a document. We use these changes to deconstruct our sense of a complete and unified final whole. Instead, we get a sense of a series of related texts, of a work manifesting in different forms, and of stages of a revision process for which we were not present. I am especially interested in the last of these categories: collation tools allow us to uncover revision histories that might be otherwise obscured. They help us to uncover past stages of the writing process, breaking apart a text that might seem concrete and fixed and make it appear fluid and subject to change.

The illusion of a final unified text is a problem for textual editing, and collation tools have helped us to solve it for decades. This same problem, the tendency to think of texts as final objects with no prior histories, is at its core one of the key difficulties facing student writers. There is a danger for students to think of writing as crafting a marble structure – you chip away at it piece by piece until it forms a perfect, fixed form – the form it was meant to possess all along. Instead, I want to argue that collation tools can be used by teachers to help students conceive of writing as a kind of assemblage, a piecing together that instantiates one possible combination among many of a set of textual components. This mode of writing is, by contrast, characterized by play, transformation, and fluidity.

I will talk about two tools today in this context - Juxta Commons and Google Docs – and the exercises I use with each. The former is a collation tool proper, and, while the latter is more typically used for collaborative writing, it lends itself quite readily to the practice. So my focus here is on the practical – how to think about and use these tools for to teach writing and revision. I hope to tease out more of their implications in the discussion.

Juxta Commons

Juxta Commons, probably familiar to many, is the latest iteration of Juxta, a piece of software that allows a user to upload multiple textual witnesses and, at a glance, discern the differences. The tool’s digital nature means that the process is quantified and streamlined – no laboring over the collator. It also has the benefit of offering a number of visualizations for graphically understanding the differences between two witnesses, a fact that I find helpful for talking about student writing.

A potential writing exercise for use with Juxta is simple: a student writes a paragraph, and they then rewrite that paragraph several times. Finally, the student uploads each version to Juxta before writing a brief reflection on the differences between the drafts. What remains constant? Where do changes cluster? Do these edits indicate any special anxiety or concern with any one particular element of the writing process – transitional sentences, thematic chaining, logic, etc.? Do the ideas themselves stay the same? Fixating on these details can allow students to conceive of writing as an assemblage of various components that result in the illusion of a coherent whole.

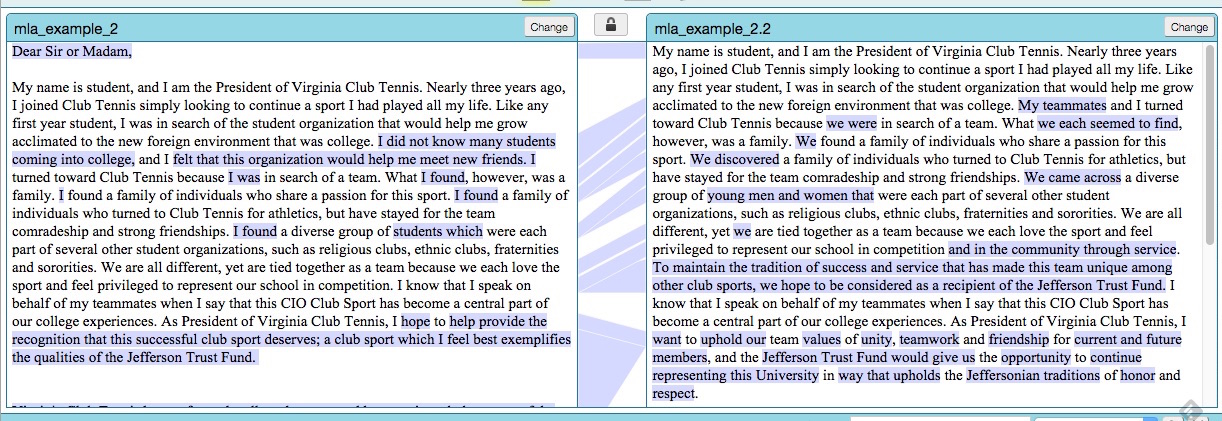

In the example above, the student is writing a grant proposal for his tennis team. In an early draft, the class noted that the writing held the team at too much of a remove when the author wanted to stress its importance to him as a second family. Such a charge can seem like a big task, but processing the paragraph through the Juxta assignment throws into sharp relief the minute edits created in a revision to create such systemic change. Comparing the two revisions in Juxta, we can see that, by and large, the student revised the subjects of this first paragraph. “I” becomes “we,” and “friends” will become a “family.” He works to increase the sense of unity among the group of people he describes, a unity that will later become essential in his argument that the organization provides more to the community than just a place to play sports. The Juxta assignment allows a student better insight into how each of these component pieces can easily be sent into motion and radically change the character of the whole document. A large, sweeping suggestion like “adjust your tone” becomes revision by way of a thousand moving pieces. Much more doable.

Juxta Commons has the added bonus of being envisioned as a commons - an online community of textual scholars. It is quite easy to share sets with others, and it would take little effort to set up a repository of shared collation sets among a classroom. To encourage objective reflection as a component of writing, I would ask each student to write a short reflection on a different student’s collation set, observing the differences and reflecting on the minute changes that got them there.

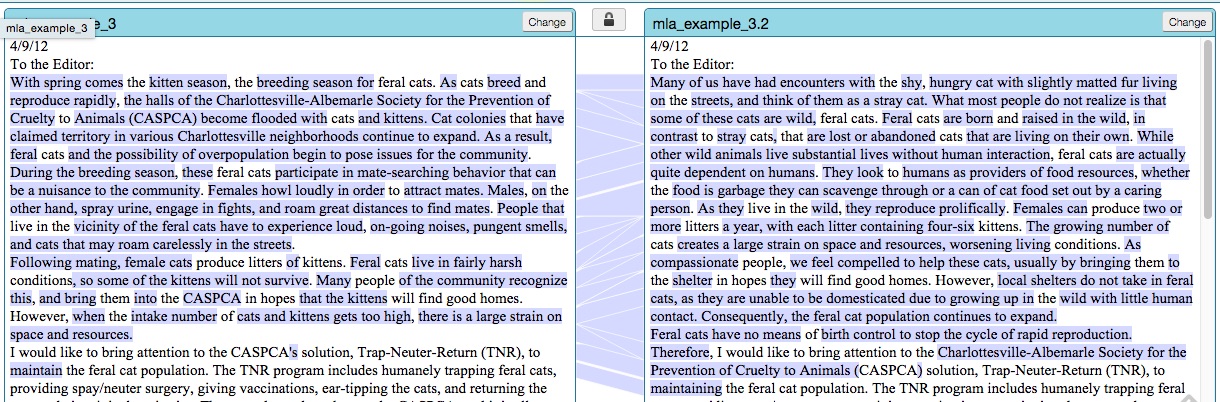

Juxta’s strength as a collation tool is also its limitation for the sort of teaching exercise that I am describing. Juxta has the benefit of being quantitative: its visualizations can offer users quick and accurate depictions of things that might otherwise go unrecognized – a missing comma, or a single different word. Juxta works best with large documents that are largely the same. But if the corresponding passages become too different Juxta will be thrown into disarray.

While it is very good at processing texts to find small differences, the software does not quite work if the documents are too different from one another. Its system allows for either exact similarity or difference at the level of character. It cannot tell, for example, if you have reworded a particular phrase or removed it entirely. The paragraph in this example was heavily rewritten, with only a few words in common between the two drafts. While this sort of at a glance collation could be useful to identify revised sections in longer documents, it does little to unsettle the idea of writing as a search for a fully realized whole. Juxta Commons works best for helping students to see the massive change that can be wrought by a collection of small changes.

Google Docs

One of the difficulties with using Juxta to collate is that it relies on a student’s already extant drafts – revision must already have taken place, which seems to defeat the whole purpose of an exercise designed to unsettle the writing process. Google Docs is not a tool made for collation, but I do think that it can helpfully generate just those many witnesses that could be collated. By using Google Docs as a collaborative writing space, classmates can help another generate different textual possibilities for a single sentence. My use of Google Docs in conjunction with a discussion of writing first came about in an advanced course on Academic and Professional Writing. We talked a lot about editing in the class, and many of the conversations about style took this shape:

Student A: “Something about this word feels strange, but I don’t know what it is.”

Student B: “What if we moved the phrase to the beginning of the sentence?”

Student C: “We could get rid of that word and use this phrase instead.”

Those statements are hard to wrap your head around. Just imagine if those conversations were spoken. Talking about writing can only get you so far: writing is graphic, after all. As I write and edit, I try out different options on the page. I model possibilities, but I do so in writing. Discussing the editing process without visual representations of suggested changes can make things too abstract to be meaningful for students. They need to see the different possibilities, the different potential witnesses. I developed an exercise that I call “Writing Out Loud” that more closely mirrors my actual editing process. Using a Google Doc as a collaborative writing space, students are able to model alternate revisions visually and in real time for discussion.

The setup requires a projector-equipped classroom and that students bring their laptops to class. Circulate the link to the Google Doc ahead of time, taking care that anyone with the link can edit the document. The template of the Google Doc consists of a blank space at the top for displaying the sentence under question and a series of workspaces for each student consisting of their name and a few blank lines. Separate workspaces prevent overlapping revisions, and they also minimize the disorienting effects of having multiple people writing on the same document.

We usually turn to the exercise when a student feels a particular sentence is not working but cannot articulate why. When this happens, I put the Writing Out Loud template on the projector with the original version of the sentence at the top. Using their own laptops, students sign onto the Doc and type out alternative versions of the sentence, and the multiple possible revisions show up on the overhead for everyone to see and discuss. After each student rewrites the sentence to be something that they feel works better, ask for volunteers to explain how the changes affect meaning. The whole process only takes a few minutes, and it allows you to abstract writing principles from the actual process of revision rather that the other way around. How does the structure of a sentence matter? How can word choice change everything? What pieces of a sentence are repetitive?

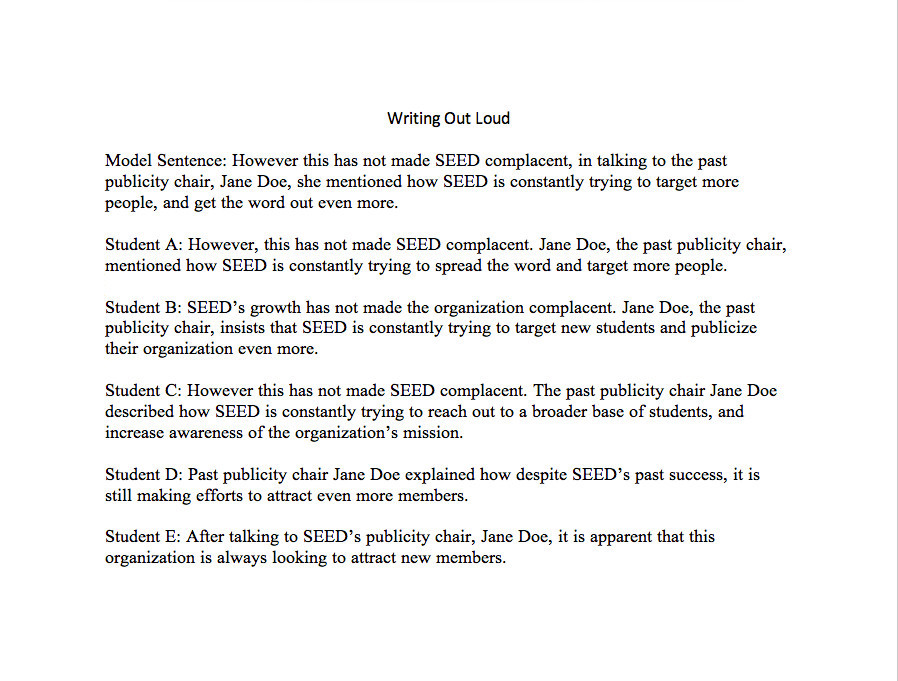

I especially like this exercise because it asks multiple students to engage in the revision process. It is always easier to revise when you have critical distance on a piece of writing, and outside editors with no attachment to a particular word or phrase can offer just that. In the above example, the sentence under discussion contained the colloquial phrase “get the word out.” The class offered a range of alternatives that range in their formality. Instead of receiving an edict to professionalize their tone, the student gets a glimpse of many possibilities from which he can choose. The exercise also allows the choices to exist side by side, making collation possible in a way that the usual revision process makes difficult. Most students, I would wager, work with one or, at most, two drafts open at a single time. Google Docs can allow a number of possibilities to emerge.

The Google Docs exercise works better on micro-edits, revisions at the level of the sentence. The standard process of the exercise—write, collate, and discuss—would take far too long with anything longer than a few lines. The exercise can be particularly useful for those sentences that carry a lot of importance for entire arguments: thesis statements, topic sentences, the first sentences of the document, etc. Where Juxta is entirely quantitative and offers hand graphic visualizations of textual difference, this Google Docs exercise relies on you and the students to collate the materials yourselves. You can recognize subtle differences – a reworded idea vs. a dropped idea, for example. It trains students to internalize the practice of collation and reflect on the interpretive possibilities offered by such differences.

Closing Analysis

I find that students often think of editing as an intense, sweeping process that involves wholesale transformation from the ground up. Modeling multiple, slightly different versions of the same sentence can allow for a more concrete discussion of the sweeping rhetorical changes that even the smallest edits can make. In this sense, I think using these tools in the classroom allows students to conceive of a single composition as one instantiation among many. Forcing them to compose several different models means that the writing process will be looser. Collation as composition offers students a subjunctive space wherein they dwell in possibilities. It is a vision of composition as de and reconstruction, as a process that is constantly unfolding.

Digital tools uncover how writing is really always already such a fluid process, and they can allow students to see their own composition process in this way while they are still in the thick of it. Digital collation can offer students the chance to think of their own works as messy, subjunctive spaces, as things in flux. By allowing multiple possible versions of the same text to exist alongside and in relation to one another, they can allow students to slip between different textual realities. Most importantly, the process severs the link between the quality of an idea and the manner of its presentation. Instead of one right answer, students can see that there are many possible solutions to any writing difficulty.

I have touched on how exercises like these can also encourage students to distill writing principles from the process rather than the other way around. They can also help students to discover editorial principals through their own writing. I am imagining here a praxis-oriented approach to teaching textual editing where practice leads to principal, one where scholarly readings might come after a student has written an essay, revised it, and, in effect, produced their own edition of their text. An exercise with Juxta might lead to a discussion of eclectic editions, while Google Docs could lead to a fruitful discussion of accidentals and substantives. I am not suggesting that these sorts of exercises replace the good work performed by studying classic editions, reading about editorial practices, or producing one’s own edition by carrying out the steps of the editorial process. But in a class that has an explicit focus on composition, exercises with tools like Juxta Commons and Google Docs can help connect textual criticism with writing pedagogy.