Digital Humanities Pedagogy and Opportunities for Hope

16 Oct 2019 Posted in:digital humanities pedagogy talks scholars lab Crossposted to the Scholars’ Lab blog

In September, I visited Emory University in conjunction with the launch of their new graduate fellowship for students aiming to incorporate digital projects in their dissertations. This is the second of two posts sharing materials from the events I took part in while there. I was asked to give a workshop on project development for graduate students as well as an open talk on digital humanities pedagogy. The text of what follows pertains to the open talk I gave, where I was asked to give a broad overview of how the Scholars’ Lab works with students. I write a talk for situations like these, but I try to avoid straight-up reading the text (more info on how I approach public speaking in DH available here). So what you will see below is more like a roadmap of the general gist of what we talked about. I did not consult the text too much in the moment. The only other relevant piece of framing that you will need is that I added the phrase “he works for the students” to the end of the bio I gave Sarah McKee (Senior Associate Director for Publishing at the Bill and Carol Fox Center for Humanistic Inquiry) to read when she introduced me. Talk begins below!

Hello! I’m Brandon Walsh. I am the Head of Student Programs at the Scholars’ Lab, a community lab for experimental scholarship in all fields, particularly informed by digital humanities, spatial technologies, and cultural heritage. You will hear a lot more about what we mean by that in the talk to come, one that I have titled “Digital Humanities Pedagogy and Opportunities for Hope.” Thank you so much for having me and for coming today to hear me talk. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to speak with you.

I wanted to first start out by offering a couple links and thanks. If you need access to the slides or the transcript of this talk (or you’re interested in what I shared with your students in the workshop earlier today), you can find those resources at this top link. I have also made a Zotero collection here with all the resources I mention in the talk in case you want to take a look at them later on. And finally, most importantly, I wanted to take a moment to express gratitude to everyone whose work has brought me here today. I’m very grateful to all my colleagues in the Scholars’ Lab whose work you will hear about in a moment, especially Amanda Visconti, Ronda Grizzle, Jeremy Boggs, Laura Miller, and Shane Lin. And I would also like to express my thanks to Sarah McKee, Lisa Flowers, Anandi Silva Knuppel, and all the ECDS students for making this trip possible and invigorating.

Sarah asked me to give a high-level overview of the Scholars’ Lab and how we work with students. I will do that today, but my standard disclaimer about the Scholars’ Lab is that we are a complex entity with many different folks doing many kinds of jobs. And you will get a different path through our work depending on who you ask. I am the Head of Student Programs, so given my work and interests you might come away from this talk thinking, “they only work with students.” This is not true! We have an R&D team and spatial technologies staff that work with the entire university, students, faculty, and library staff alike on a variety of different projects related to digital scholarship, digital preservation, and digital project development. So what you will hear about today is about my own particular corner of the lab. One of my colleagues might have a different, overlapping story. My story is about our students, though I am happy to help flesh the full picture out for you if you would like during discussion.

At the risk of tipping my hand too early, I wanted to offer an overview of what is to come. I’ll move back and forth between example and theory, but the main takeaways, if I had to offer them are these. First, DH pedagogy does not just take place in the classroom, and it’s not just about DH. Second, digital humanities pedagogy is pedagogy. Third, DH pedagogy at every level should consider, intersect with, and reconstruct desire paths through the academy. I’ll talk more about all of these ideas in a moment. I’m not going to be offering any practical thoughts on how to carry out DH pedagogy, though I’m happy to do so in the discussion afterwards. This is more a talk about the animating philosophy for DH and pedagogy as we try to practice it in the lab, about the idea that teaching can offer spaces for hope in the university.

When Sarah invited me here today, as is usually the case for things like this, she asked me to send her a bio. I always dread this part of giving talks. When I was a student, I always felt like I hadn’t done enough, and I hated hearing people read my short list back to me. Now that I have been working in the field for a bit longer, I still find it embarrassing for different reasons. So I decided to take a cue from Chad Sansing of the Mozilla Foundation and do something with this moment of discomfort. In his bio on Medium he mentions, a bit tongue in cheek, “I teach for the users.”

I don’t want to spend my entire time here reiterating the plot of the 1982 movie Tron, but, in my reading at least, Sansing’s bio is a riff on a line from that movie: “he fights for the users.” The line describes the titular character of the movie, a security program who fights other fascist computer programs on behalf of the users who have been locked out of the computing world. It’s a lot. But I like Sansing’s adoption of it here, and I wanted to try it out for myself. I like the way that his bio ties up his identity into a kind of mission statement. “Who am I” becomes “why am I here?” He is here to teach, and he’s here to teach the users how to take back control of the web.

The bio I gave Sarah ended with the phrase “he works for the students.” That phrase is a mission statement and also the subject of this talk, which will deal with how we work in the Scholars’ Lab to have care and consideration towards our student collaborators suffuse everything we do. I’ll talk against the ideas that teaching only takes place in the classroom and that administrative work has nothing to do with teaching. I’ll start with what we do in the lab “for the students” and why. Second, I’ll contextualize this briefly as happening against the backdrop of a larger crisis in higher education. Third, I’ll offer thoughts about how we can shape a DH pedagogy that responds to such emergencies.

To begin. In the Scholars’ Lab, we try to start by approaching the whole student. We try to think about how our decisions affect lives and need to be informed by lives. Because administrative choices matter in big ways for people. When an application date gets set, who is eligible for a fellowship, or what kinds of work we allow as permissible in a particular context - choices like these affect the journeys our students are on.

So I would like to start by talking about paths. This image by an English Councillor circulated on the Digital Pedagogy Lab hashtag last month, and it illustrates a phenomenon called a “desire path” or a “desire line” – I would wager we have all seen them before. Desire lines are the paths made, over time, by people stepping on the same, unplanned path. They typically represent the organic actions of pedestrians as opposed to what was planned by the city designer. In this case, based on the Twitter conversation, the path you’re looking at appears to have been made over time by cyclists in response to the constructions you see on the left, obstacles deliberately put in place to discourage cyclists speeding along on this paved path. It is not difficult to imagine the accessibility issues caused by this same construction choice.

I’m taken with this image as a metaphor for the life of a graduate student in academia (caveat here that most of my comments will be about graduate students given who I tend to work with, but I think they are relevant for students generally as well). The image certainly resonates with me, coming as I do to work in the library without a library professional degree but instead with a PhD in English. In short, our students might get into this space for one reason, and we might imagine paths through it on their behalf. But everyone finds their own way through their own education and often through different means and to different ends than we anticipate. I certainly got pulled sideways at a certain point and wound up in a place I could not have envisioned at the beginning of my time at UVA.

I often wonder in related ways about my own activities in the administration of the Scholars’ Lab and in higher education more generally. In my role, I’m often making or offering small choices that are likely to affect the course of someone’s journey through their time as a student. These individual, local interventions in a person’s path - how do they fit into the larger journey for them? Am I helping people to form their own desire paths? Or am I the one throwing up barriers? How can I take those barriers down or help pave a new path to help the route be a little easier? Who am I to be making such decisions for other people? How can I take the responsibility of these choices as seriously as possible?

Given this logic of the desire path, for student programs to service your community in a perfect world you will be offering a diverse slate of opportunities. Because your student population does not just have broad and diverse disciplinary research questions – they also come from a range of different backgrounds and life situations. An MA student, at UVA at least, has a different course load and does not typically teach. This puts them in a fundamentally different category financially, with different pressures and needs, from a PhD student. And what works for one will not work for the other. That is to say, any conversation about DH pedagogy, for me, starts and ends with a discussion of the lived circumstances of the students. Our student activities in the lab are foremost informed by a consideration for the diverse contexts and backgrounds that our students represent.

We try to make our programs fit those many needs, and we try to offer a number of different ways in to do so. The phrase “for the students” that I mentioned earlier is also pretty close to a page on our website where I try to collect everything that a student might be interested in knowing about us. This is the “For Students” page of the Scholars’ Lab website if you would like to check it out at http://scholarslab.lib.virginia.edu/for-students. I will talk about a few of these pieces in detail first from a nuts and bolts standpoint and then a theoretical one, though I am happy to talk in more depth about any one of them.

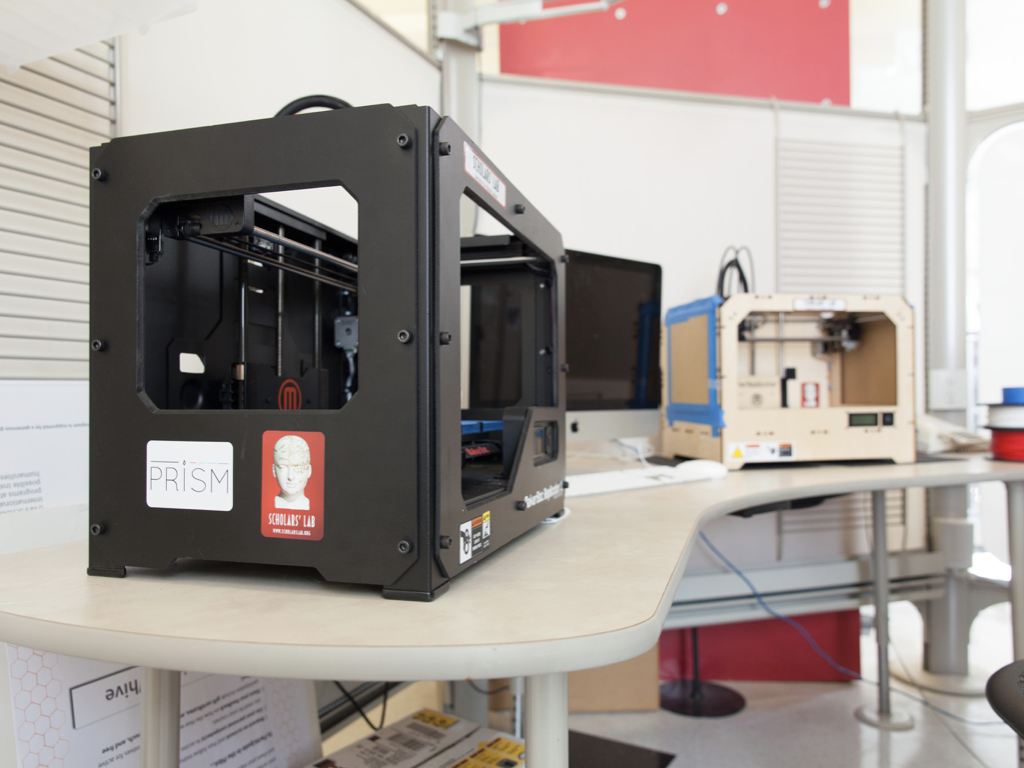

We regularly offer two hourly wage positions for students in the lab. The first is that we employ hourly students in our makerspace as technologists assisting community members with 3D printing jobs, experimental electronics, or sewing and wearable electronics. No experience is necessary for a student to take on the role, and we typically train people up on the job. There are a number of makerspaces on campus, but ours is distinct for being committed to teaching folks how to do the printing themselves. So you don’t drop off a file and pick up a print - you learn how the technologies work. And our makerspace primarily caters to humanities students, though we do get a fair amount of traffic from science students who tend to find our space less crowded than the ones provided by the Engineering School.

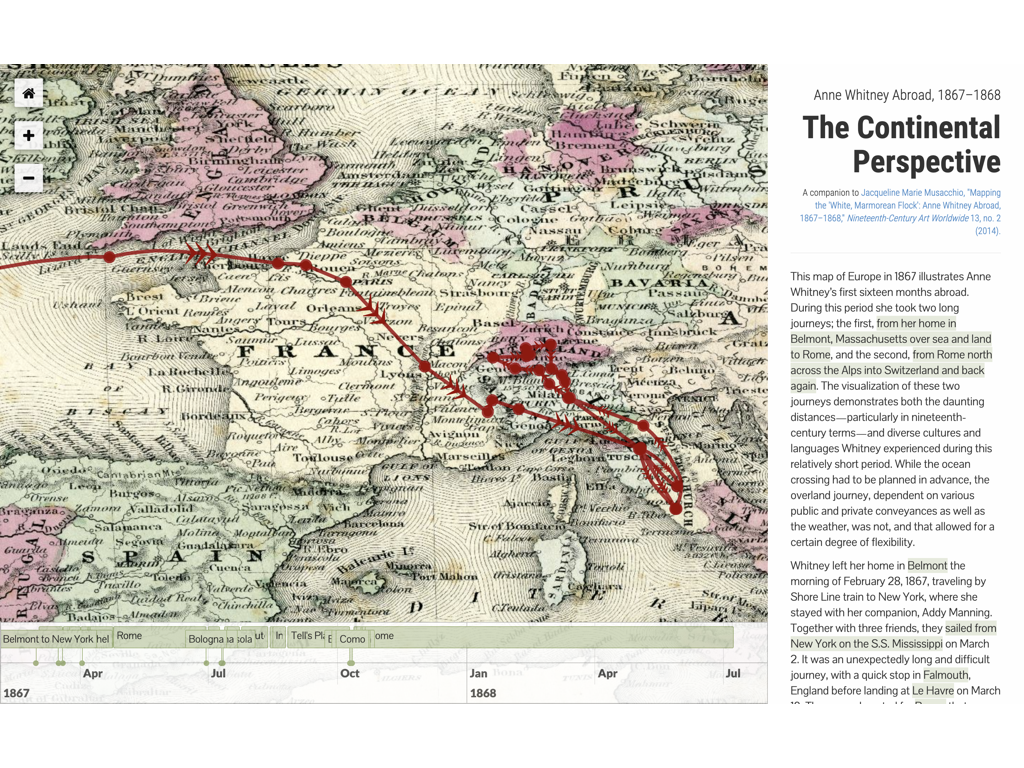

Second, our GIS specialists Drew McQueen and Chris Gist service needs related to spatial technologies for the entire University, and they regularly employ a GIS student collaborator to assist them in doing so. This student and these projects can come from across the university – not just the humanities. And they also frequently collaborate with local and regional governmental organizations on a variety of different geospatial projects. Our students are there at each step along the way as collaborators.

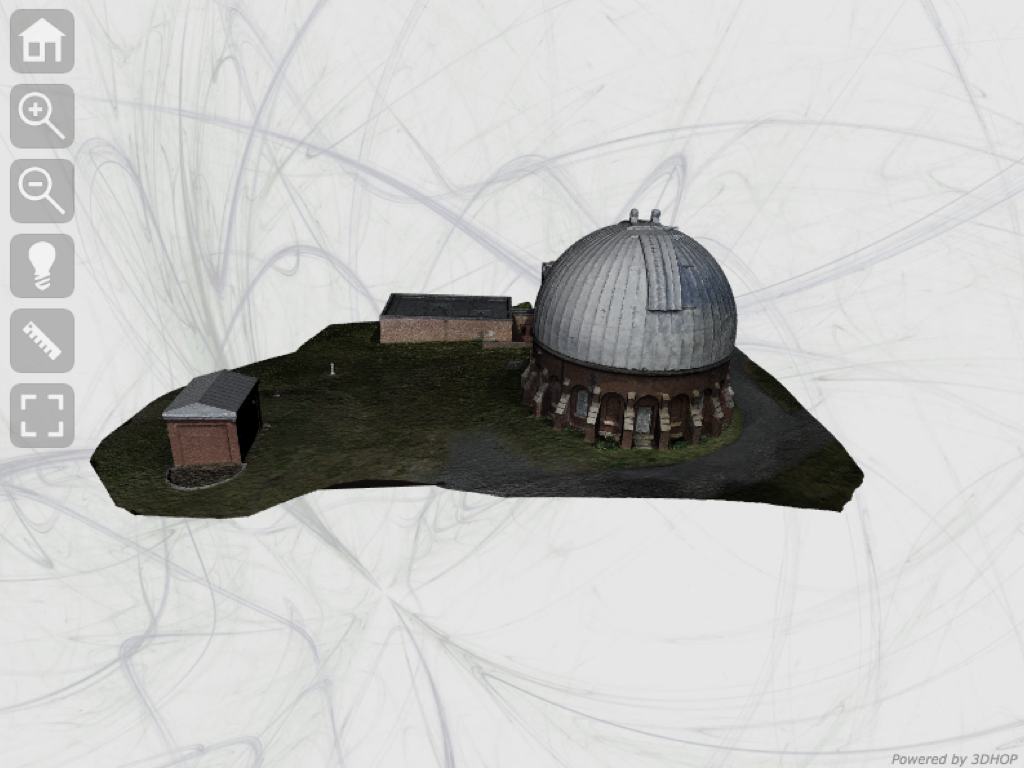

We also engage students in an internship for course credit through the architecture school, where our 3D Data and Content Specialist, Will Rourk, collaborates with them on the scanning of artifacts and spaces that are significant for cultural heritage purposes. They often carry out site visits in the region, and Will also collaborates with local museums on scanning objects of importance to them.

Will then engages those same students in the production of 3D data based on these objects. Through the process, our student interns get a deep introduction to all different parts of a 3D data pipeline, and the work that they all do together is truly impressive. The previous tweet and this 3D model all relate to the McCormick observatory on UVA’s campus.

Beyond these opportunities, we also offer two yearlong fellowship programs that offer deeper dives into digital humanities. These are the programs that I most directly supervise. Our higher-level DH fellowship is for advanced PhD students at the dissertation stage who want to work on a project related to their research. They teach some, but they are largely doing a deep dive into developing a professional portfolio that will serve them on the job market. And our Praxis Program is something of an introduction to digital humanities by way of project-based pedagogy. The six students in this fellowship each year form a cohort and work collaboratively on a self-designed project over the course of two semesters. The students drive the program: the fall feels more like a seminar or workshop with us at the front of the room, but the spring is owned by them. We flick them in a direction, but they take the project and develop it in a way that feels authentically theirs both in spirit, scope, and shape.

So that’s a piece of what we do in the lab, and you might have noticed just how much we do for students. I am well aware that the Scholars’ Lab is in a privileged position as far as resources go, both for centers for digital research and even within our own library. Over 2/3 of our budget goes directly to students, and we work directly with about 50 students each year. That’s a lot. As anyone who works with budgets knows, our own budget is the result of longstanding and ongoing campaigns for more resources. I am grateful for allies in the library who recognize the value of supporting students and especially to those who fought for years before I was involved to get those numbers to where they are. These numbers are not settled, and we have to work to keep them every year. But I bring these points up to ask - what can an institution without this level of support do? What can an individual without the support of an institution do? What are small actions we can take in our pedagogy - particularly our DH pedagogy - to help the desire paths our students are trying to make for themselves, even when we’re limited by resource scarcity?

For me, one way of approaching these questions is to think more deeply about what we mean when we think of pedagogy. I remember one conversation I had about teaching, when a colleague offhandedly said, “Oh well I don’t teach.” And a nearby colleague agreed as well. I remember doing a double take. These were people who, to my mind, were constantly engaged in the work of teaching.

Even besides the workshops they regularly give, these were people who mentored students, helped with their projects, and pair programmed beside them to help them learn. Furthermore, they’re fantastic teachers. The general culture in the Scholars’ Lab is one in which we constantly engage in peer mentoring. Digital Humanities is hard - there are so many fields. No one knows all of it, and we try to offer a spirit of generous assistance to each other every day as we find our way through this field. How, then, did I have an entirely different view of these colleagues than they did of their own work?

I think my colleagues were equating teaching with teaching classes as instructors of record. And, to be fair, sometimes I’m asked whether I am teaching or not in the upcoming semester, and I don’t quite know how to respond either. While I sometimes teach semester-long courses, my primary work is not in such traditional modes of instruction. While it’s not really the question they’re asking, my gut response is usually to think, “when am I not teaching?”

This is to say that pedagogy is not something that only happens in the classroom. I especially like the way that Sean Michael Morris describes this notion in an interview with Jesse Stommel. They’re two prominent scholar-practitioners of critical digital pedagogy, and they’re the chief instigators behind Digital Pedagogy Lab. In an interview about their new collection An Urgency of Teachers, Morris describes pedagogy as not something we just enact in the classroom. Instead, it’s a system of beliefs that we carry with us. A way of orienting ourselves in the world. Or at least it should be. If we think about teaching and pedagogy as things that only take place when we’re in front of a classroom or with our names in an LMS, then I would argue that we’re not thinking of teaching in the fullest possible sense. The spaces for teaching are vast, and our students many. To be “for the students,” we need to think of education as a way of life. As something that runs deeper than sharing material with students. This about how we view them and their work. We’re always teaching, whether or not we’re in front of students for a whole semester.

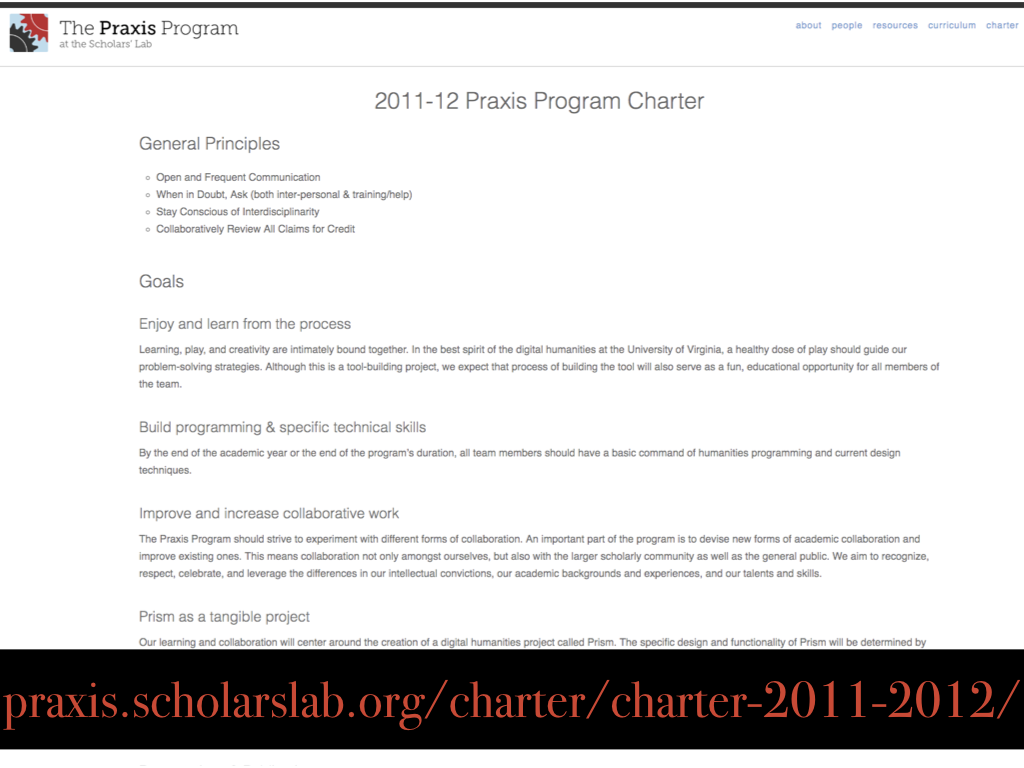

It’s one thing to believe having values like these are important. But in the Lab we also believe it’s important to share them, and now we’re getting into the philosophy behind what we do. We believe it is important to write our work philosophies down and to explicitly say them in public. In the Scholars’ Lab, we believe in explicit statements of values called charters, documents that spell out your beliefs, goals, and ambitions. We have had our cohorts of Praxis students put charters together describing their shared ambitions and values each year for the last nine years. Here you have one of the Praxis charters from one of the early cohorts. They cite free and generous credit, transparency, and an awareness of each other’s diverse backgrounds and disciplinary interests as important markers for them. The hope is that by encouraging our students to examine their shared group identity we will draw out a richer sense of themselves and each other.

Last year in conversation with Jeremy Boggs we realized that, even though we have our students write a charter every year, we hadn’t actually done one of our own, as a staff, for our student programs. We possessed a general charter for the lab, but we thought our student programs needed to explicitly share their own pedagogical philosophy and promises. It was time to make things clear and explicit. So we wrote one together. For the students.

You can find the whole charter on our website at http://scholarslab.org/student-programs-charter, and I’d encourage you to read it. It’s a document that is not perfect, but it’s one that I’m glad is out in the world. Here are a few excerpts from it that describe our approach to teaching.

We’re here, and we care. We trust in students. We teach the whole person. We’re committed to advancing pedagogical practices that are equitable, just, and ethical. It’s important that our students know where we stand, and one of the first things I have our students do is read this document along with the more general charter for the Scholars’ Lab. Our pedagogies, the ways we think about our work with students, should be shared with them. In the Lab we believe they should be part of the conversation.

Lest you think this is an artifact of the quotes I chose to emphasize, the charter doesn’t actually talk an awful lot about technology. It does occasionally, but only in oblique ways. We want our students to own their projects as well as their domains. We want them to fail in public in a way that pushes their comfort zone but not their safety. We all feel like imposters - many of us everyday. Some of you probably feel like imposters right now. I know I do. These points imply a certain interdisciplinary approach to technology, even though they are not specific to digital humanities.

And it’s also not lost on me that I’ve spent most of this talk on digital humanities pedagogy not talking all that much about digital humanities pedagogy. And that’s part of the point.

Digital humanities pedagogy is pedagogy. I’ll say that again. Digital humanities pedagogy is pedagogy. Similarly, to go back to Digital Pedagogy Lab, I’ve heard Sean Michael Morris say that the “digital” part of DPL is just an excuse to get people in the room to talk about pedagogy. The definition of digital humanities I usually give to students is one I draw from Elizabeth Grumbach: DH is asking humanities questions of technology and asking humanities questions with technology. DH pedagogy is certainly teaching that engages with those topics, materials, and methods, but leaving it there is akin to saying that you only teach if you’re an instructor of record.

Because I feel a tad guilty staying wholly theoretical I want to pause for a moment to say that there are great resources for digital humanities pedagogy from a practical perspective: I highly recommend Using Digital Humanities in the Classroom, co-authored by Claire Battershill and Shawna Ross, and Digital Pedagogy in the Humanities, edited by Rebecca Frost Davis, Matthew K. Gold, Katherine D. Harris, and Jentery Sayers. These resources are exemplary for those seeking practical advice and examples on how to teach digital humanities.

But what I mean by “DH pedagogy is pedagogy” is that, for us in the Scholars’ Lab, a digital humanities pedagogy is one that thinks deeply and critically about the teaching itself and the interpersonal, societal, and institutional changes it purports to make. It’s not just about the classroom. That is to say, we certainly teach DH methods, tools, and thinking, but we’re more directly trying to think about how and why we do this work and what larger implications it might have. Digital humanities might be an especially good opportunity to make these sorts of interventions, and that brings me to the quote that the title of this talk is riffing on.

“Opportunities for Hope” is a play on Henry Giroux quoting the work of Paulo Freire. In full it reads: “Hope demanded an anchoring in transformative practices, and one of the tasks of the progressive educator was to ‘unveil opportunities for hope, no matter what the obstacles may be.’” For Freire, education in its best shape was always about social reform, and he called for new forms of teaching that empowered students and upended traditional modes of instruction like the banking model for education that assumes students are empty vessels who need to have the knowledge of the instructor given to them only to regurgitate it back. And it’s this same spirit of transformation that we bring to the students who work with us in the Scholars’ Lab. How can our pedagogical practices as digital humanists open up space for new ideas for students, but more importantly, for imagining new lives? How can we unveil opportunities for hope, no matter the difficulties? Beyond simply giving them tools and methods, how can we go further and make the teaching we do be a political intervention?

More specifically, how do we unveil opportunities for hope in a climate like the one in which we all live, where it often feels higher education is on fire? Tenure track positions are vanishing, adjunctification is on the rise, and an enormous number of students and staff are in precarious positions. A so-called “free speech” crisis threatens actual free expression and freethinking in our classrooms. I could go on and on. I spoke about the privileged position the Scholars’ Lab is in, in terms of funding. But, no matter how much funding we’re able to direct to students, it’s never enough. There are always more students applying for fellowships than we have spots to give. Since I’ve been teaching, students have spoken with me about homelessness, food insecurity, precarious finances, uncertain job futures, mental health crises, chronic health conditions, and more. And I know the student populations I’ve worked with are not unique in higher education. How do we find hope for ourselves and for our students in the face of these situations? And what can pedagogy do here? I’ll offer three provisional responses to this question. In the face of a crisis in higher education, we should think of the work we do as creating spaces of shelter and intervention, as empowering student voices, and as changing culture more broadly.

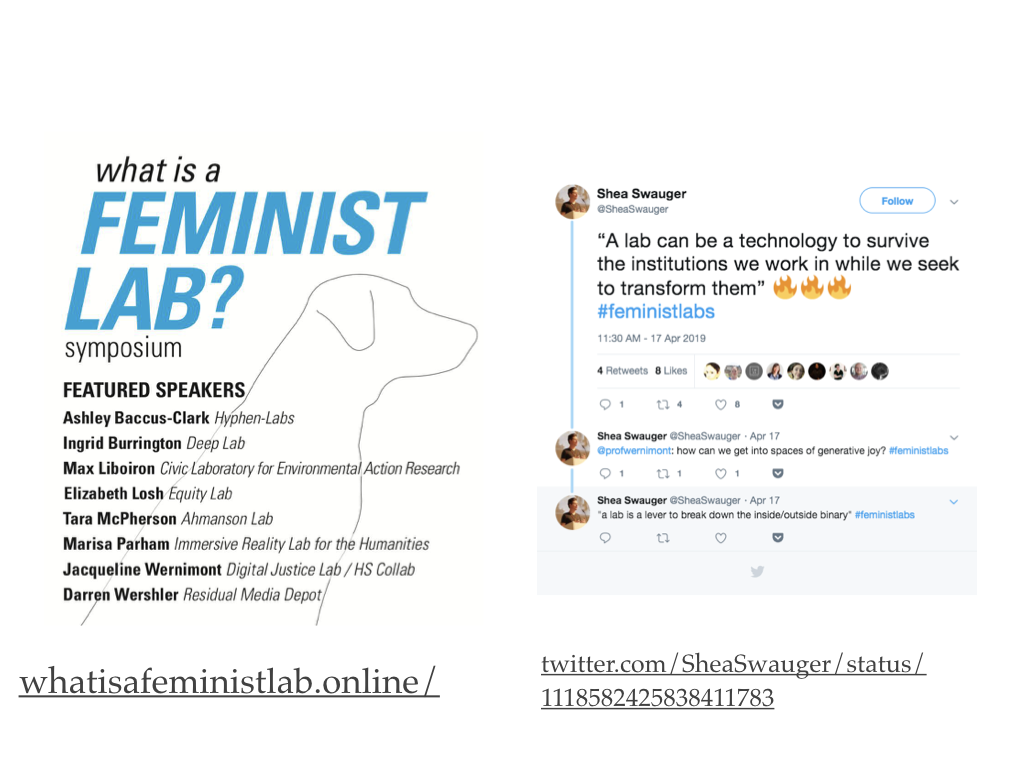

My first response is that we can think of the teaching work that we do in digital humanities spaces as work that seeks to shelter and also to intervene. “What is a feminist lab?” was a symposium that took place at University of Colorado Boulder earlier this year. I got permission from Jacqueline Wernimont to cite her remarks, quoted here: “A lab can be a technology to survive the institutions we work in while we seek to transform them.” Our students in the Scholars’ Lab frequently refer to it as an oasis in the larger academy, by which I take them to mean that we value their futures, their concerns, and anxieties in ways that are not as well supported elsewhere. As they develop charters and have conversations about the values they want to develop and promote during their time with us, I often encourage them to think of it as an opportunity to shape the sort of kind, generous, and transformative space they want to see in the academy.

That is to say, we also engage students in a wide variety of support that is not particular to wage employment or research. Some of these are programmatic. We offer mock interviews if students wind up applying for library or digital humanities related jobs. We read materials. We circulate job postings relevant to this kind of work. But more generally we have frank conversations with students about our lives and theirs and try to make space for them in ways that might otherwise be difficult in other parts of the university. Our fellowships don’t carry grades, we allow deferment of our fellowships, and we generally try to make lives a little easier. For us, this is the work of pedagogy, and the fact that we are operating in a library-based digital humanities space helps facilitate this. Your own mileage may vary, as your circumstances are likely to be different. Given your own limitations, how can you use your position as teachers to inject more kindness into the academy?

Second – we can respond by asking, “where are the students?”

It’s important that we keep student interests and needs in mind. They are an important audience for our work, but sometimes they can disappear from the conversation when we discuss long-term strategy. So simply asking how students fit in is a place to start, and even small actions like making sure the word “student” appears on mission statements can be important interventions. But we can go further. Student voices need to be included in discussions about their own education. Digital humanities pedagogy is often quite amenable to this, as project-based pedagogy of the sort that is common in DH can often invite students to have an active role in shaping their experiences. The UCLA Student Collaborator Bill of Rights has other good advice for how to engage student voices and to make sure that you’re doing so in an ethical way. It’s a touchstone for us in the Lab.

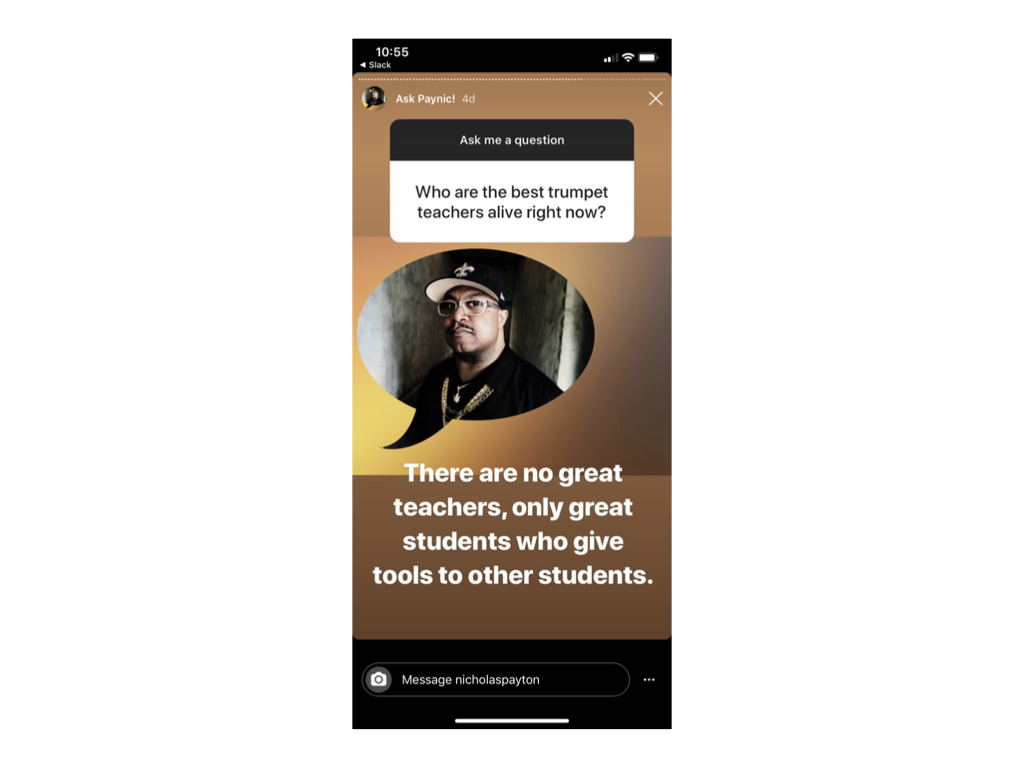

The Small Liberal Arts Community (as exemplified by ILiADS) offers fantastic models for how you can engage students as true partners in research projects and disrupt the labor distinctions that all too often exist in our work. I’d encourage you to explore the ILiADS site for examples of projects that might offer models as you think through how to work with students. For my money, the SLAC community is offering some of the most exciting digital pedagogy work. This kind of flattened distinction between student and teacher, as much as possible, is something we try to aim for in the Scholars’ Lab. It’s expressed in a concise way, I think, in this Instagram story by Nicholas Payton, a prominent jazz trumpet player and composer.

In a recent “ask me anything” session on Instagram, Payton was asked, “Who are the best trumpet teachers alive right now?” He responded, “There are no great teachers, only great students who give tools to other students.” That is the world I want to live in. A world in which the Scholars’ Lab students see themselves as experts, and in which their staff and faculty see themselves as equal partners in the pursuit of knowledge.

We’re all students at the end of the day.

This can sometimes feel difficult to square with digital humanities, though, where often we quite literally have things we need to share with students that they are encountering for the first time. One thing we try to do in the Lab, beyond adapting our curriculum to the needs of the students, is talk to our students about the work of teaching and learning in which we are all engaged. We talk to them about why we are doing what we are doing, what difficulties we’re having, and what thoughts they might have for making a better experience.

For example, I mentioned the Praxis Program, our yearlong fellowship where our students go from soup-to-nuts with digital humanities, from knowing little to launching their own collaborative digital project by the end. For years, the interdisciplinary makeup of the team has been a recipe for real interpersonal conflict. Usually in March. Every year, right when the rubber hits the road and they’re trying to launch their project. Finally this past year we decided to talk to the team about it.

During the second session of Praxis this year, Amanda Visconti and I ran a discussion for our new cohort of Praxis students on good collaboration and community. And we laid this pedagogical problem out – we talked about issues we had in the program in the past not as interpersonal issues between specific people but as expressions of larger difficulties in collaborative work. We discussed what seemed to help and what did not. What’s more, we also talked about what good collaboration looked like for each other and how the students could make sure they treated each other with respect and kindness first. The students took the conversation very seriously. Last year was the best year yet as far as collaboration is concerned, and Amanda and I just ran the conversation for a new cohort last week. In short, there’s no need to treat pedagogy like something that has to be hidden from your students. Particularly in DH, as it asks so much of students professionally, interpersonally, and emotionally, we need to involve student voices in the development of good teaching practices. They deserve it, and everyone’s experience will be enriched.

Third, and I think it’s apparent from this talk, we have to think about the work that we do, even at the level of the individual assignment, as engaged in a larger project of shifting the culture of the university. When I spoke to the graduate students earlier today, we ended our workshop by talking about values. The workshop was called “getting from here to there” with a digital project, but the point was that there is always going to be another project. Another semester. Another student. It’s more important to think about why you’re doing this work: what are the animating philosophies behind what you’re doing? I’ve tried to give you a glimpse today of the “why” for the Scholars’ Lab.

I encouraged the students earlier to think about their work as opportunities to open up small spaces for more generous, kind, and productive spaces in the academy, to imagine the future they want to see into the world. In the Lab we see our work as part of a larger attempt to shift the culture of the university, both in terms of what graduate training in the humanities can look like but also in terms of what kinds of conversations are acceptable.

At UVA, we’re plugged into a larger network of like-minded programs working to train graduate students for a broad range of lives and future careers. This program, called PHD+, has been instrumental for us in helping to see that the work we’re doing as being part of a larger movement to rethink what graduate education can look like. Thinkers like Katina Rogers and Cathy Davidson, both at CUNY, and Sean Michael Morris and Jesse Stommel, co-founders of the Digital Pedagogy Lab, have been instrumental for me in seeing the work of the classroom as intimately connected to the work outside it. And, to go back to my point about student voices, we talk about these issues explicitly with our students. We have a session on diverse career options for them, on labor precarity and employment in digital humanities. We’re not solely interested in getting them jobs; we want to make sure that they can find their ways to happy futures no matter the outcome.

So to bring it back to an earlier image and earlier questions - when working on DH pedagogy decisions I’d encourage you to think about this image. I know I will. How are our decisions helping people navigate their own desire paths through the university? Throwing up new barriers for them? Paving new roads? How can we make even small assignments part of larger culture shifts? How might digital humanities pedagogy, in libraries and out of them, make space for these conversations?

That’s my talk. Thanks for listening. I’m happy to talk more about Tron, the Scholars’ Lab, nuts and bolts of digital humanities pedagogy, other opportunities for hope, and anything else you’d like.