Finding Your Lever: DH Pedagogy in a State of Crisis

17 Mar 2025 Posted in:digital humanities pedagogy talks

What follows is my contribution to a roundtable at UVA entitled “Digital Futures of Graduate Studies in the Humanities.” The event celebrated the release of the edited collection of the same name distributed through the Debates in Digital Humanities series. As a part of the session, Gabriel Hankins, Alison Booth, and I gave remarks describing and reflecting on our published contributions to the volume.

In the 1993 Bill Murray comedy Groundhog Day, a weatherman gets trapped in a time loop, endlessly repeating the same day over and over again. It has the veneer of a family friendly comedy, but it’s actually quite dark. Hijinks ensue, but Murray’s character struggles to find meaning and purpose in a world that spins out of and beyond his control. He masters the piano painstakingly over the course of many days. He becomes the town hero. He learns everything about everyone around him. He solves everyone’s problems. He despairs and commits suicide. Numerous times. In a way, the film is about the creeping horror of existing in the everyday when there is a larger, world-warping context that everyone is ignoring. It’s also a meditation on the small changes that you can make in these circumstances and, ultimately, whether or not they matter.

Murray’s experiences in this film are similar to my experience writing my contribution to the collection that we’re discussing today.

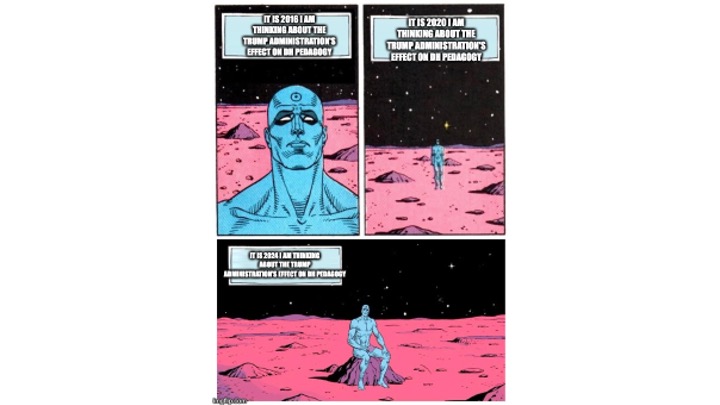

Put another way, let us transition from Murray to internet memes. In 2016 I was thinking about what the Trump administration meant for DH teaching and learning. It’s 2020 I was thinking about what the Trump administration meant for DH teaching and learning. It’s now 2024—I’m still thinking about what the Trump administration means for teaching and learning. What are the effects of the recurrent crises in higher education through which we are living? On graduate education in particular? on digital humanities pedagogy in general? On those of us trying to teach, learn, and live in the academy, digitally or not? The Trump administration’s recent apocalyptic executive orders threaten to dismantle the financial infrastructure of the American university system as it has existed since the mid-twentieth century. The recent arrests of student protesters are but one recent instance of an ongoing and full-on war against campus protest and free speech. I have had to edit this paragraph numerous times in the past weeks because the situation keeps evolving so rapidly that one’s head spins.

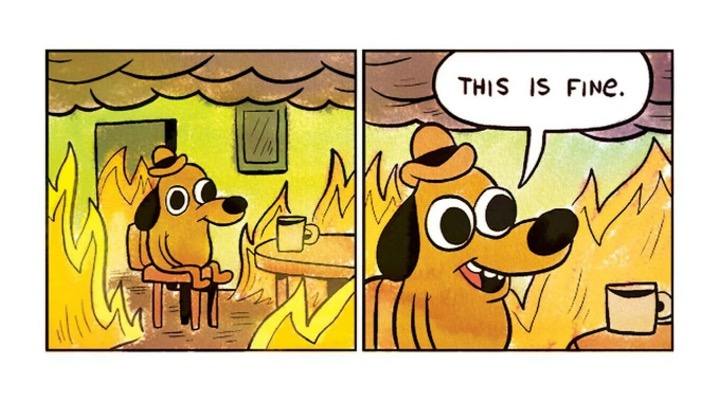

We are in a state of extreme crisis. But when has that not been true?

To put it plainly, the house is on fire in academia. It can feel all too easy to remain focused on the small world in front of you, ignoring the actual burning building around you. To focus on the coffee. To go about business as usual, teaching within our disciplines, within our own subsection of digital humanities. Waiting for someone else to deal with the fire. Waiting for an institution to take meaningful change and actions in the face of world-ending threats.

This is all by way of framing the essay from the excellent collection we are celebrating today. If you can’t guess, my contribution was entitled “The Futures of Digital Humanities Pedagogy in a Time of Crisis,” and I will give a bit more context for those who haven’t had time to read it.

I was in a very angry space while writing this article, and its publication story was one of the more disorienting and time warping writing experiences I’ve ever had. If I recall correctly, I actually decided against submitting an abstract to the collection because I felt overwhelmed with life and our political climate. When I finally submitted to the extended deadline it was against the backdrop of the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic. I wrote the actual article in the summer of 2020 during the height of the Black Lives Matter protests related to the murder of George Floyd. The collection itself came out just after Trump’s re-election to a second term. And, of course, this event today is taking place just a couple months into the new Trump administration. Same as the old, but more intense, ever-present, and chaotic.

This long timeline is not unheard of in academic publishing. But I dwell on it because the piece is about crisis and how we respond, about the unfolding of history as we try to do our everyday work of teaching and learning in DH. I found it dizzying to return to the piece at each of these stages in the publication process and to feel as though I needed to reframe it around a new crisis. At each return, what I had written in the past felt profoundly alien. The past writing also felt immediately, urgently relevant to what I was feeling in the present. Even though the specific context was constantly changing, I was writing to and for a digital humanities pedagogy framed by a higher education in crisis. The realities of these crises are not new. They have always been there for people who are paying attention. The particular forces ranged against the work we do as educators might change depending on the particular day, week, or month. But the forces working against teaching and learning are always there.

To summarize the argument of the essay: we cannot practice a neutral, apolitical digital humanities pedagogy in this kind of historical moment. The context of this work is not neutral, for teachers or for our students. In the world of graduate education, our students are buffeted by systemic inequality, racism, a vanishing job market, and more. We do not teach in neutral spaces or in neutral times. It is morally and ethically necessary for us to develop a digital humanities pedagogy that engages with the reality of the world in which we find ourselves. It is also a question of survival. It’s clear more than ever that the world outside the walls of the classroom impacts the work we do inside them, whether or not we would want it to be so. If we want a digital humanities that’s worth surviving into the future then our work must engage with the present. Our teaching must reclaim the crisis.

The most recent and coordinated attacks from the Trump administration on funding and freedom of expression at American institutions of higher education demonstrate the urgency of this call. The current environment, its far-right actors, and the administrators seeking to appease these forces for political expediency are destabilizing forces. They unsettle the infrastructure that makes DH teaching and learning possible. We cannot carry on with business as usual in the classroom. Because there very well could be no classroom in the future. We cannot bury our heads in the sand and look to the coming semester because there very well may not be a new term. If we want to have a digital humanities pedagogy worth maintaining and worth surviving, it must take the needs of its community and the political urgencies of the moment seriously.

I offer a number of ways in the piece for DH instructors to meet the moment, mostly by amplifying the work and actions of people who are already doing this labor and have been doing so for years. I name check everything from amplifying the voices of student protests, to joining your union, to giving space, funding, and support to scholars of color who have been doing this work for a long time. And more. I suggest that we all look at the different spaces in which we work to find what we can do. And here I want to note that my title is a an extended riff on “‘We All Have Levers We Can Pull’: Reforming Graduate Education” by Ashley Cheyemi McNeil, Beth Seltzer, Brian DeGrazia, Jimmy Hamill, Katina Rogers, Rachel Arteaga, Stacy M. Hartman, and Stephanie Malak. I highly admire the clarity of that piece and its associated calls to action. We all have something we can do. If you’re a DH administrator who has direct control over budgets that you can make more equitable, you can make a difference. If you’re a workaday classroom teacher who can engage your students in classroom assignments in the pursuit of justice, you can make a difference. If you’re a student with something to say, you can make a difference. The time is now for us to find ways to double down on teaching that matters. As Kevin Gannon has argued, our students deserve better from us than a pedagogy of neutrality.

I tried to practice this ethos of solidarity in the course of producing the essay itself, which I wrote differently than normal. I wrote the piece backwards, beginning with the works cited. I worked from a process of accretion, accumulating a variety of relevant things and then relentlessly citing those people, projects, and organizations. The argument felt less like it emerged from my own voice and more as though I was channeling a community of people whom I admired. I tried to work through my own difficult feelings about the cultural moment by gathering the resources others had ready to give to that need. The full text of my contribution to the volume is 2108 words. Of those, the argument itself only clocks in at 1210 words, meaning that 43% of the text is citations or footnotes. That distribution felt pretty wild to submit, but it also felt deeply, profoundly like the only way to begin my piece of the conversation. Radical solidarity and action across institutional and professional lines is the only way forward for digital humanities pedagogues. Fewer lone scholars. More communities of thinkers, teachers, and students. Organizing themselves. More pulling of levers.

That’s a bit by way of summarizing my piece, but I wanted to wind towards a close by talking a bit more about the editorial process it went through. Being a piece in the Debates in Digital Humanities series, the piece went through several rounds of review and editorial feedback. Gabe might be able to comment a little bit on what this collection was like to bring into being as an editor. I want to dwell on two critiques I received during the journey to publication.

I got two specific pieces of feedback that felt especially relevant to bring into discussion here:

- Would anyone disagree with what I’m saying?

- Am I arguing something that is specific to digital humanities pedagogy, or is this an argument about higher education more generally?

I don’t bring those up in a “can you believe what reviewer two said??” sense. Both these notes made the piece stronger. They also articulate reasonable objections to what I am discussing that are worth putting into the room. I enfolded responses into the essay itself, but I thought it worth sharing them here as we move to discussion.

To the first point. I agree that in the abstract someone of a broad political inclination might generally agree with what I call for here. Who would not want their work to be meaningful, to be politically impactful? In practice, though, it is very difficult to convert such agreement into action. It is exceedingly challenging to channel temperament into the kind of work that could impact one’s economic, social, or professional livelihood. It’s very hard to get people to have some skin in the game. If you’ve ever tried to have an organizing conversation with someone about taking any kind of direct action, you know this to be true. If you’ve tried to get someone to join a union, you know that is not an easy conversation, even with those whose politics seem to make them an easy recruit. In short, I have a question for those who might broadly agree with what I have been saying. What does it look like for you to take concrete pedagogical and political action based on this agreement? With your teaching? With your administrative work? How can you exercise your own power, influence, and privilege, such as you have them? What levers are you willing to pull?

As to whether or not this argument is specific to the digital humanities or a broader argument about higher education: fair! After all, I did not talk that much about actual DH pedagogy here today. In the piece itself I cite a range of DH work, but I think the critique is valid for the written essay as well. My answer to the comment is yes, there is a way in which you could certainly make this argument discipline agnostic. And to some degree this is by design. The kind of academic, class, and labor solidarity that I’m calling for is one that is wall-to-wall in the organizing sense. It should extend broadly to include all disciplines, to all higher education workers. I do believe that this particular political moment is an especially fraught one, and the way we get through it is by organizing together. By seeing our work, the work of education, as having a political valence to it beyond our particular methodological disciplinary silos.

But levers lie in both directions. The critique can be both broader and more capacious than digital humanities pedagogy but also specific in the way it manifests here for us and for our community. Digital humanities can bring something distinct to the struggle. I believe, for example, that we have a unique perspective on the ways in which education intersects with the infrastructure of the university. So much of the work that we do cuts across disciplinary, institutional, and administrative silos. How often does your digital humanities work require you to talk to IT professionals? To write grants? To talk to your librarians? To engage students in a kind of collaborative work that goes beyond the typical labor of the humanities classroom? It’s often very hard for digital humanities teachers to conceive of their work as existing in isolation, closed within the walls of the classroom, simply because it is so often the work of many people from across the university. You have no choice but to think about policy that affects the work that you’re doing. Digital humanities teachers are especially well-positioned to frame our work as something that can enact the kind of change we want to see in the infrastructure of the university precisely because we cannot escape it. There are plenty of examples of how to do this. Maybe it’s about organizing a data rescue event, collecting government data before it disappears as a vehicle for teaching data preservation. Maybe it’s about using digital humanities budgets as a vehicle for teaching both DH administration and the political economy of the university. Maybe it’s about articulating and practicing equitable labor practices in your classroom DH assignments. Maybe it’s about working with your students to build a project that tracks political injustices as you see them practiced in ways that intersect with your coursework. Fill in your own teaching ideas. They will be better than mine.

In short, the article is a call to find your own pedagogical levers, to find your own ways in which your digital humanities teaching can be impactful. Because your pedagogy is already subject to politics, already is political, whether you know it or not. It’s up to us to try and harness that connection.

The spaces of teaching and learning are not closed to the outside world. This has always been true, but we better start acting like it before the classroom disappears altogether. Perhaps, though, what we need right now most of all is a digital humanities pedagogy that lives and works in the streets. If we want to have a digital humanities in the future, if we want to have a digital future of graduate education, if we are to have any future at all, we need to start thinking about how our digital humanities pedagogy marches on and in the present.

Thank you.