Frustration is a Feature

03 Jan 2018 Posted in:digital humanities talks pedagogy The following talk was given at MLA18 as a part of Panel 203: Anxious Pedagogies - Negotiating Precarity and Insecurity in the Classroom. Technically I suppose the title should be “Anxiety Is a Feature,” but the alliteration was too tempting.

Thanks for putting this panel together, Shawna. And thanks, all of you, for your thoughts - I’ve learned a lot from our exchanges leading up to this panel.

I’m the Head of Graduate Programs in the Scholars’ Lab, a digital humanities center at the UVA Library. I want to come at the question of anxious pedagogies from the perspective of my role in the lab, where I often teach programming and DH skills and methods in addition to my primary duties, which are developing and administering the lab’s educational and professional development programs for graduate students. I work with students very self-consciously trying to step outside of their comfort zones, and I’d like to think about the anxieties associated with these cases in particular.

I want to ask what, exactly, it is that we’re teaching our students. If you’re a sighted reader of English, your skin has probably been crawling due to the grammatical error in my slide here. And that’s part of the point - this error is the subject of memes (but it’s one I constantly make in emails). You might be embarrassed for me and wish someone had pointed it out to me ahead of time. Let’s explore that.

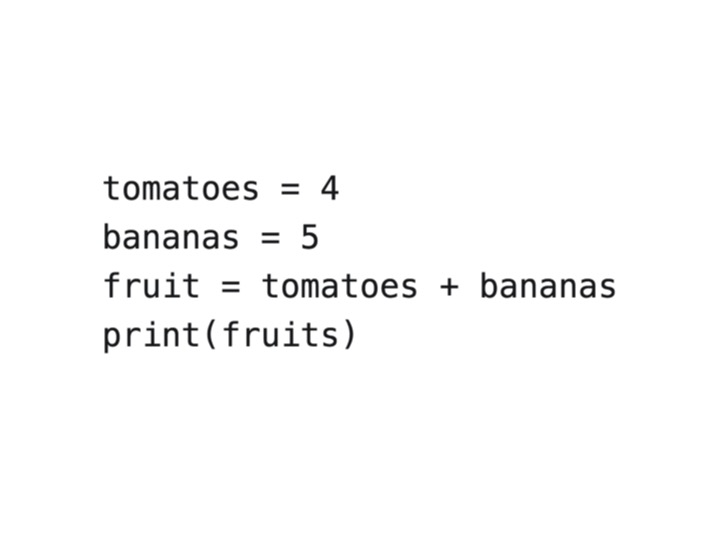

There’s a Python error of a similar kind in this slide. In programming, such small mistakes are major issues that can cause a project to fail. They’re also common for beginning programmers and DHers. A student has an error like this, and, quite understandably, they ask for help from the teacher. The instructor, as a human being, quite understandably wants to help. I want to talk about that moment - the point at which a student needs help and the nature of the contribution that we as colleagues and mentors are prepared to give.

The ability to identify the kinds of problems I’m pointing out depends a lot on background and training. To expect such problems to be immediately identifiable makes a lot of assumptions about education, literacy, and background that no instructor should make. This is as true of the first example as in the second, which expects that someone has a background in programming and so knows that a computer would not be able to infer a relationship between the variables ‘fruit’ and ‘fruits’ - adding the extra ‘s’ in that last line by accident causes problems.

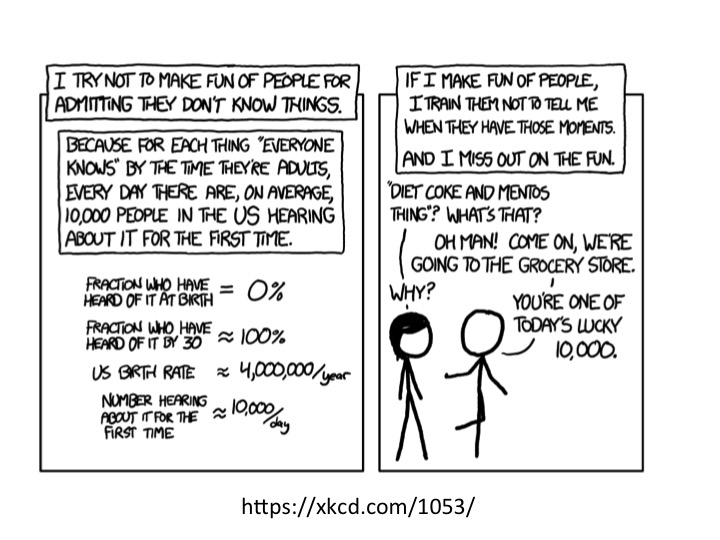

I have seen so many students stare, with mounting frustration, at chunks of code, feeling that they are beyond them, that issues in code represent some failing on their own part rather than a natural part of programming (we all make mistakes). Sure, my job is to teach them the skills with which they can solve these problems - the syntax that will prevent such errors in the future. But it’s also to help them recognize that no one is born knowing this stuff. Born knowing anything. And that such anxieties and frustrations are part of what all of us all deal with on a regular basis.

I am not suggesting that we should approach such student frustration as feelings to be worked past or to be toughed out. Instead I want to suggest that the most important, radical act that we can make as teachers is to center frustration and anxiety in our teaching. This feeling, that of knowing something is there but not seeing it, or of knowing something is wrong but not how to address it, are central to the very idea of what it means to learn and to teach. Sianne Ngai might call these “ugly feelings” - those feelings that lead to no cathartic action and that are associated, instead, with pause, frustration, and paralysis.

I’d suggest that our primary role as teachers is not to teach any particular content. Nor is our primary role to teach methods. Our ultimate aim should be to help students learn how to learn, how to keep going with the material outside the context of our courses. And, importantly, how to do this work with, through, and alongside such difficult emotions.

In DH we often valorize failure and what can be learned from it, but it can be difficult to know how to deal with the feelings associated with it. I’ve tried to develop exercises (drawing upon the work of Wayne Graham, Jeremy Boggs, Amanda Visconti, and Bethany Nowviskie) that help students sit with and think through the frustration and anxiety associated with failure. To teach web design, I ask students to draw a series of prototypes for websites using pencil and paper, some explicitly designed to fail, so as to develop a better sense of what it might mean for a website to succeed. Or I ask students to explore a set of programming exercises that have bugs artificially introduced to them as a way of helping them learn concrete steps for exploring problems in the face of mounting anxiety.

I’d love to hear from all of you if you have any thoughts for how to center, rather than expel, frustration and anxiety from teaching, learning, and the classroom. These issues are especially salient while teaching programming to humanists, as the interdisciplinary nature of it requires people step out of their comfort zone. But as others on this panel have articulated so well, these issues extend to the whole person. Beyond the content we teach and the act of learning it - our students are living in states of continual anxiety. To say nothing of the personal, social, or systemic traumas to which many of them have been subjected about which we may never know.

Most of what we do in the Scholars’ Lab is help students navigate these situations in a professional context. Most of what I do tends to revolve around convincing students that they are good enough. That they are qualified enough to teach a workshops on DH or to apply for any number of DH or alt-ac jobs. That a little goes a long way. That imposter syndrome is something felt by everyone. That their work has worth.

There are a number of things we can do as administrators to help mitigate the anxieties of our students. Advocate for them by actively campaigning for the bureaucratic status to serve on committees, teach courses, and offer them the support that they need. Petition our legislatures and administrations for more just labor relations. Figure out the small bureaucratic things that translate to big pains for our students - things like delayed payments, long turnarounds on applications, gatekeeping practices.

My point, our point, really, is that our students and colleagues are consistently in positions of anxiety and frustration - in and out of the classroom. So I’d ask what can we do to make our institutions, our classrooms, and our one-on-one interactions with our students more empathetic, but also more consciously aware of and engaged in the negative emotions they might bring out. Because as the title of this short talk suggests - frustration and anxiety are not pedagogical bugs. They are features. Woven into the very texture of what it means to be human and to be a learner. The question is - what are we prepared to do about it?