Getting from Here to There

19 Sep 2019 Posted in:digital humanities pedagogy talks scholars lab Crossposted to the Scholars’ Lab blog

A few weeks ago, I visited Emory University in conjunction with the launch of their new graduate fellowship for students aiming to incorporate digital projects in their dissertations. This is the first of two posts sharing materials from the two events I took part in while there. I was asked to give a workshop on project development for graduate students as well as an open talk on digital humanities pedagogy. The text of what follows pertains to the workshop for students, where I was asked to give a broad overview of how to approach project planning and some activities for helping them think through their work for the year. I essentially tried to condense the greatest hits of the Praxis Program into 90 minutes. I was asked to give a 30 minute talk and 60 minute workshop, but I’ll get into how we shifted things around below.

First, a few caveats. For one, I write a talk for situations like these, but I try to avoid straight-up reading the text (more info on how I approach public speaking in DH available here). So what you’ll see below is more like a roadmap of the general gist of what we talked about. I don’t remember consulting the text too much in the moment, and I know for a fact that the last few paragraphs were dramatically different in person. Second, and related - since this was meant to be a workshop and not a lecture I planned on a fair amount of discussion with the really thoughtful and engaged students.

All of this is to say that I planned on deviating from my plan, and I tried to represent that below. In the text that follows you’ll find the actual running text of a talk and workshop plan along with notes to you, the reader, marked with [sidebar: brackets] describing how I modified things in the moment to adapt to the group and the conversation as it unfolded. You’ll get a mix of both the script for the presentation and some notes on how I managed things as it diverted from expectations. It might get a little confusing, but I imagine it could be interesting to see how things got restructured and shifted around in the moment.

Planning for a span of time as long as 90 minutes is difficult, so I deliberately planned far more than I could cover in the allotted time just in case. I went into it knowing I’d need to be flexible. If I had to offer any suggestions for workshops in general it would be this - plan more than you need but do not try to rush to make it through your material. Let the conversation and the discussion shape the pace of your teaching, not a need to cover a particular amount of content. I always find it more helpful to do more with less. In this case, it meant that I was watching the clock from the beginning and looking for milestones along the way where, if needed, I could wrap things up.

[Sidebar: we’re in talk land now. What follows is the rough script of the talk and discussion that Anandi Silva Knuppel, Sarah McKee, and I fielded together.]

Getting from Here to There

Hey friends! How is it going? I’m Brandon Walsh, the Head of Student Programs in the Scholars’ Lab in the UVA Library. The Scholars’ Lab is a center for experimental scholarship informed by digital humanities, spatial technologies, and cultural heritage thinking. For the purposes of our conversation today, my work with students is probably most relevant. I facilitate a number of different fellowship programs and student opportunities in the lab, where I’m in charge of everything from mundane administrative tasks to more abstract things like constructing our pedagogical mission. And I collaborate with a range of people in the Lab and the Library to carry out different kinds of teaching for our community. I work with students from a range of disciplines, which means I have a fair amount of experience helping people plan, scope, and execute projects. I’ve titled this workshop “Getting from Here to There.”

[First sidebar: Anandi Silva Knuppel was the one who invited me to speak at Emory, and she gave a general orientation to their fellowship program before I started my piece. She included several photos of her children and family in the talk, and I quickly realized that the tone of my section would feel like a weird shift from hers. So, while she was presenting, I threw in a bunch of photos of the cat my partner and I recently adopted. This is Pepper, and he makes numerous appearances in what follows.]

Before we get started, I wanted to offer some resources and gratitude. If you need the text or slides of this talk for any reason, you can find them at the first link here. The second link will take you to a Zotero collection for this talk, so you don’t necessarily need to rapidly write down the links to things as we’re going. I’ve collected them for you. I wanted to credit my colleagues at the Scholars’ Lab, whose work I’ll discuss in what follows. Amanda Visconti, Ronda Grizzle, Jeremy Boggs, Laura Miller, and Shane Lin especially show up in the following slides. And, finally, I wanted to thank Sarah McKee, Lisa Flowers, Anandi Silva Knuppel, and everyone at ECDS and the Fox Center for the Humanities for the invitation to talk here. I’m truly flattered and grateful.

In terms of what we’ll cover today, I’m planning on taking you through a series of questions related to DH project planning roughly organized around questions pertaining to the how, what, who, and why of digital projects. This is my roadmap through the topic, and I’m happy to just lecture at you. But it’d be great to have questions and discussion as relevant and necessary. So please do interrupt. The conversation will be better for your contributions and better for your ideas. Ultimately this is about making it useful for you. So tell me what you need, and I’m happy to go where you want. I won’t necessarily have all the answers, but I’m happy to talk together.

[Sidebar: I had planned on running some icebreakers to get to know the students and their work, but Sarah and Anandi actually did this during their opening orientation for the program. So the slide I had planned on getting to know each other became wholly irrelevant. Instead, I realized that I should share a little bit about my own background as it pertained to the topic at hand. So during Anandi’s orientation I inserted a couple slides about the Lab and myself.]

So I’ve learned a little about you, but who am I? I work in digital humanities now, but I didn’t actually start doing anything with DH until I was a graduate student myself. I didn’t even know of it as a term until I became interested in the fellowships that my friends were doing in the Scholars’ Lab. It took a few years of finding my feet, but the digital project I worked on for my dissertation had to with Virginia Woolf and machine learning, and it was a project that taught me a lot about myself, my work, and what I wanted out of life. So believe me when I say that you are all far more advanced than I was at the same point in my career. You’re doing great! And you are well prepared for the projects you’re working on.

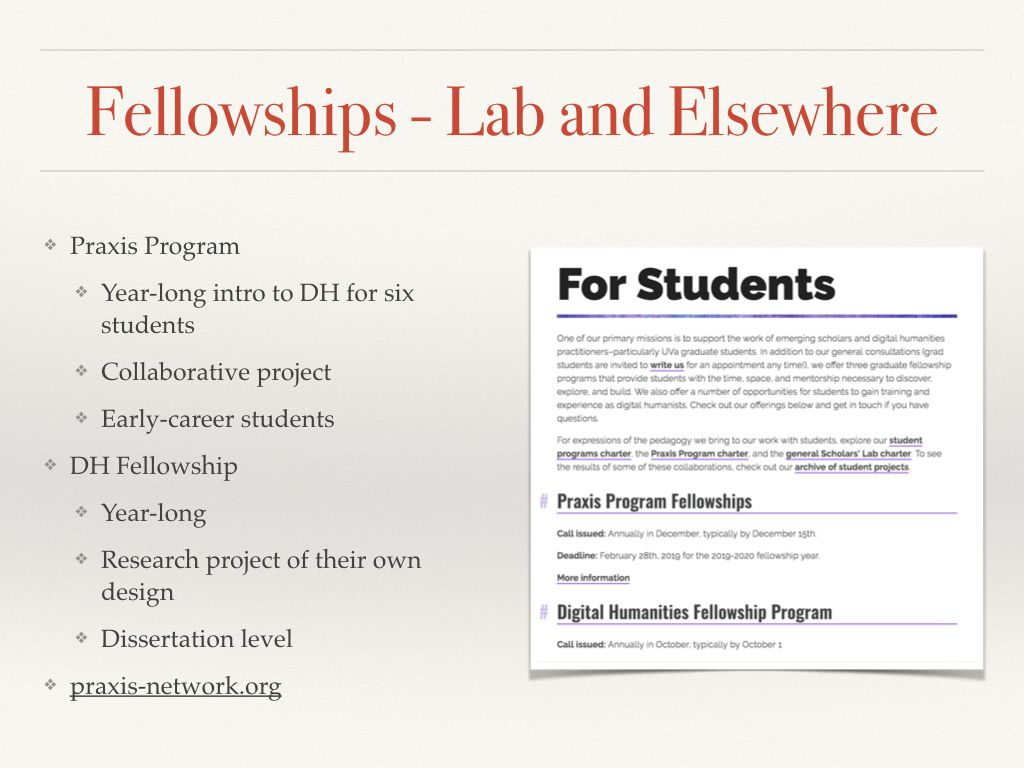

[Sidebar: During Anandi’s orientation, one of the fellows asked a question about how their own program at Emory compared to the larger landscape of digital humanities graduate programs. Was it unique? How did it compare to other fellowships? So I called another audible and inserted the following slide about the Scholars’ Lab programs so that the students could get context for how things might be structured differently. It’s different aesthetically because, well, it’s from a different talk! I copied and pasted it in quickly from the talk I’d be giving at Emory later that evening.]

Based on your question about other graduate programs in DH, I thought it might be worth pausing for just a moment to share what our students do with us in the Scholars’ Lab. At the Lab, we have two year-long fellowship programs. The Praxis Program is something of a soup to nuts introduction to digital humanities for students early in their graduate career. These students typically come in without much experience in digital technologies, but the goal for us over the course of a year is to get them in a position for them to launch their own collaborative digital project. The second fellowship listed here is our year-long Graduate Fellowship in Digital Humanities, a program for people with more experience and who are working to tie DH to their dissertation projects in some way. These students work with a point of contact on our R&D team for the year to develop their project, and students in both programs give public presentations by the end of the year. If you’re interested in learning more, I’m happy to talk at greater length about our individual programs. The Praxis Network might also be a useful resource - it’s a website that archives snapshots of several like-minded programs at one point in time, so on that project you get glimpses at several different approaches to graduate education.

Let’s get started. I titled this talk “Getting from here to there” because, to me, that’s the most difficult thing about planning any project. And this is particularly true for a student digital humanities project. I like this image because the alt text for it, the text meant to describe its contents for accessibility purposes, is “man standing in hallway.” It showed up when I did a search on Unsplash for “future.” I don’t know about you, but I have a hard time seeing a person in that photo. And when you’re starting out with any kind of digital project that’s part of the challenge. How do you get from point A to point B? How do you get your project from here to there? And how do you place yourself within it?

Now I’m just trying to show you snazzy images, but starting a digital project often puts me in this position. I feel like I’m learning to walk for the first time, and each step seems insurmountable. Each step brings new anxieties, and I’d like to know more about yours. I learned a little about your work, but I’d like to know a little more about your questions. What is the single biggest question you have right now about getting started? What is your single biggest anxiety about the year to come?

[Sidebar: I had budgeted a little time to have the students discuss concerns, but we wound up talking for longer than I anticipated (it turns out I really wanted to help them work through things). At this point, because we had started the workshop a tad late after lunch, I was already becoming aware that we were going to run out of time. We were only about 15 minutes into the 90-minute session, but I had already changed my sense of the timeline for the talk. The questions the students asked were very good. So good, that it seemed as though they were plants. They talked broadly about concerns that they might not have meaningful contributions to make to the field more broadly at this stage in their work, anxieties about finding their way into the DH community, questions about professionalization, and more. Sarah and I fielded them together. The questions worked well as a transition, because I correctly anticipated that some of them would feel like imposters.]

Those are all excellent questions. And part of the message I want you to take away today is that questions like that are all normal. It is normal not to know the answers. Behind all of your questions I heard implied another, particular anxiety.

[Sidebar: insert joke about Pepper looking stressed while working.]

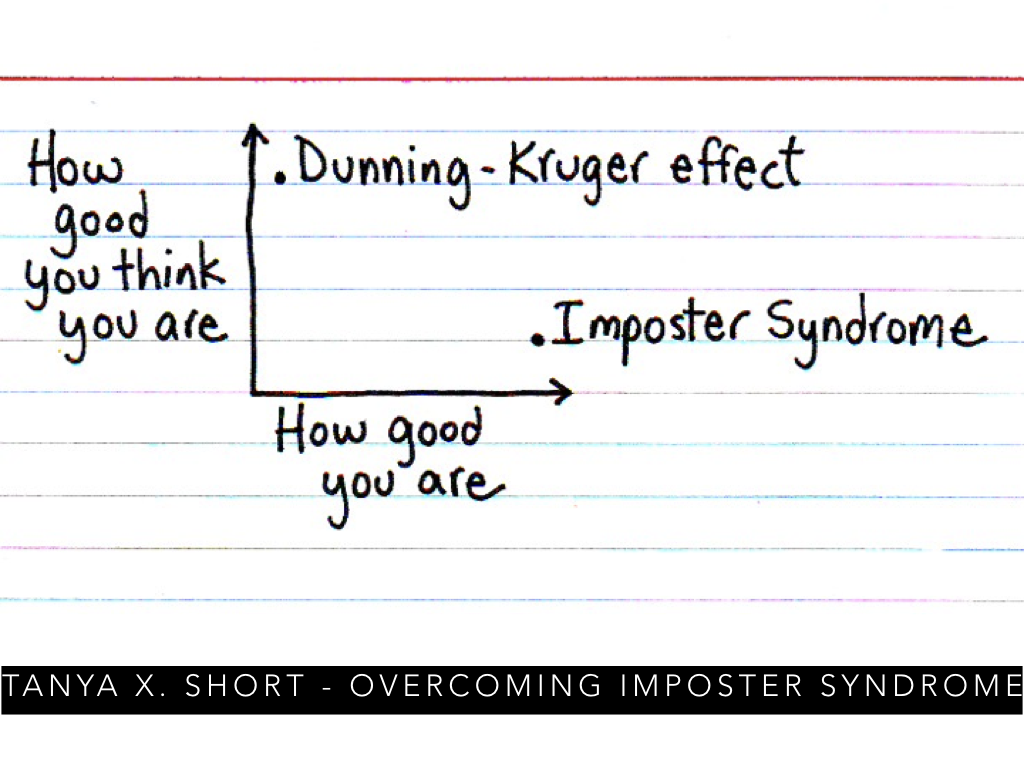

Behind your concerns, really at their core, I heard questions about imposterdom. When am I going to be exposed for the fraud that I am? I have no idea what I’m doing – when am I going to be found out? I am here to tell you today that almost everyone feels this way. And if you don’t – you’re a Dunning-Kruger, as this chart explains. This feeling – imposter syndrome – is something we live with all through our lives. I’m feeling it right now! And I think it shows that you’re a good, thoughtful, reflective, well-meaning person. This article by Tanya X. Short has some excellent strategies for working through your feelings of imposterdom. I recommend it. But I also recommend you take a deep breath, close your eyes, and recognize that you belong here. You can do this project, and you have a community of people here to help you. I’m also happy to help in any way I can if you want to reach out after this event. But more practically, there are some helpful resources and methods I can share with you for how you can get started. Because one way you can address imposter syndrome is by doing what you always do as academics. Do research. Prepare. Use the resources available to you. The process for digital work does have key differences that I can help you think through. But it is not so wholly alien and different as it might seem at first glance. I have a series of questions that I usually talk through with newcomers to digital projects as they’re thinking for the first time about this kind of work, and I’ll be giving you a version of that conversation today.

Reminder: interrupt me at any time. To begin.

How will you go about your work? On a day-to-day basis, what is the process by which you will carry out your work? You might be getting to the point where you have good, personal project management styles that work for you as you’re writing your dissertation. If you don’t, now is a good time to develop them. But it can always be helpful to hear about other strategies. Know thyself in the first instance – find what works for you and stick to it. But don’t be afraid to try out something new.

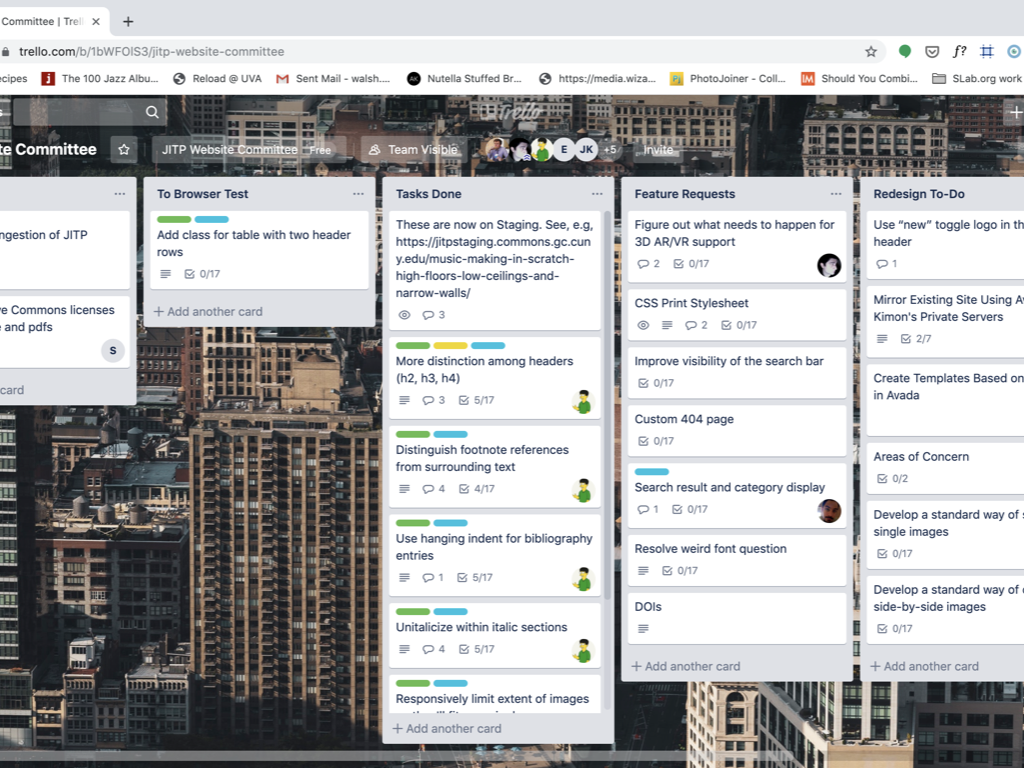

Who here has heard of Trello? We don’t explicitly use this tool in the Scholars’ Lab as a whole staff, but we use it on the technical board for one of the journals I’m involved with – the Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy. It’s pretty simple - the idea is that each task gets a card associated with it that you can comment on and move around. Nothing too earth shattering here, but these task management systems become increasingly important as your projects grow in complexity and as you begin to work with collaborators. They’re especially good for humanities projects, in particular, because we’re not used to thinking in terms like this. How do you take a complicated humanities problem and break it into smaller, completable steps? Doing this with technical work can help keep you from burning out and help you feel that you’re moving forward. It can make the whole process of getting from here to there feel doable. You’ll likely be bad at it at first and have trouble with task managing. That’s OK! It’s a skill you can develop like anything else.

If you’ve ever talked to anyone else about the way that they work, you’ve probably realized that everyone takes on projects in different ways. Even writing. When I was writing my dissertation, I would use the “add comment” feature in Microsoft Word to leave myself tasks on the document itself. Any page would have hundreds of comments that I would sort through when I sat down to write and was looking for where to begin for the day. I would be shocked if anyone else used this weird, idiosyncratic system of mine.

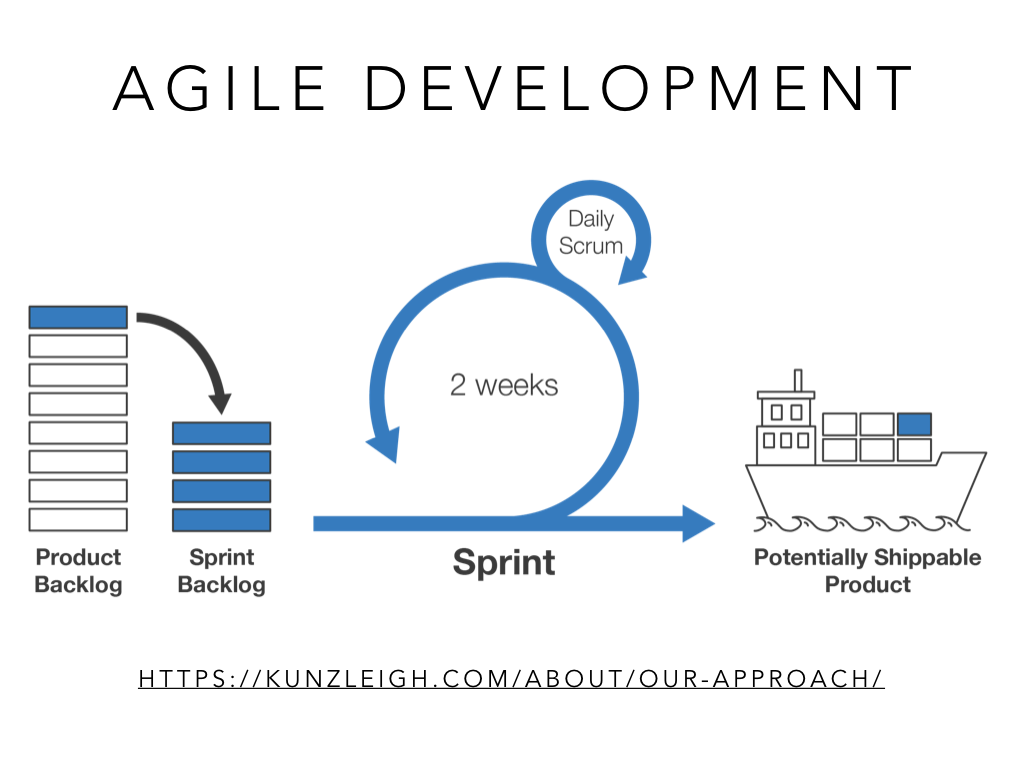

Digital work is no different - we all have different ways of going about it. But it’s helpful to get everyone working from the same book if not exactly on the same page. In a corporate context, it can save time, money, and energy if your team has a shared philosophy towards your workflow and project management. This can be true of humanities and DH work as well. In the Scholars’ Lab, we use an approach to project management called Agile Development. The basics of it are before you in this diagram. The general idea is that you work in two-week sprints (at least in the way that I implement it with our students). At the end of each sprint you reflect on where you’re at, what you need help with, and what you need for next steps. A scrum is a term taken from rugby, and it is a set of tools and methodologies for conducting these of check-ins, whether they happen daily or at the end of your sprints. In our staff scrums, for example, we go around the room and ask for two-minute updates (max) describing what you are currently working on, what is next for you, and what you are not working on. But for your purposes here today, you can just think of it as a two-week sprint followed by a meeting to touch base. And then you repeat. We do this with our fellows, who have biweekly scrums with their R&D points of contact.

That explains the center of the diagram. The left side of it refers, I believe, to the idea that you should break your larger project down into smaller tasks that you can accomplish in two-week sprints. That way you have a good sense of progress. In a student project situation, this might be as simple as “I’m going to work through this chapter from this programming book and come to you with the progress I’ve made and the questions I have.” And if a task can’t be accomplished in two weeks it’s probably actually several smaller tasks lumped into one. Break your tasks down until you find something you can do in that window of time. One last thing here – notice the emphasis on circular shapes and the word “potentially.” One of the core concepts of agile development is the idea that iteration is good. It actually saves you time, energy, and, in the corporate world, money to produce something early that might be half baked and get feedback on it. This allows you to learn from your mistakes and iterate on your materials. It requires a certain amount of humility to work like this, and it’s radically different from what we’re used to in academia. Produce something for other eyes? Before it’s perfect? Perish the thought.

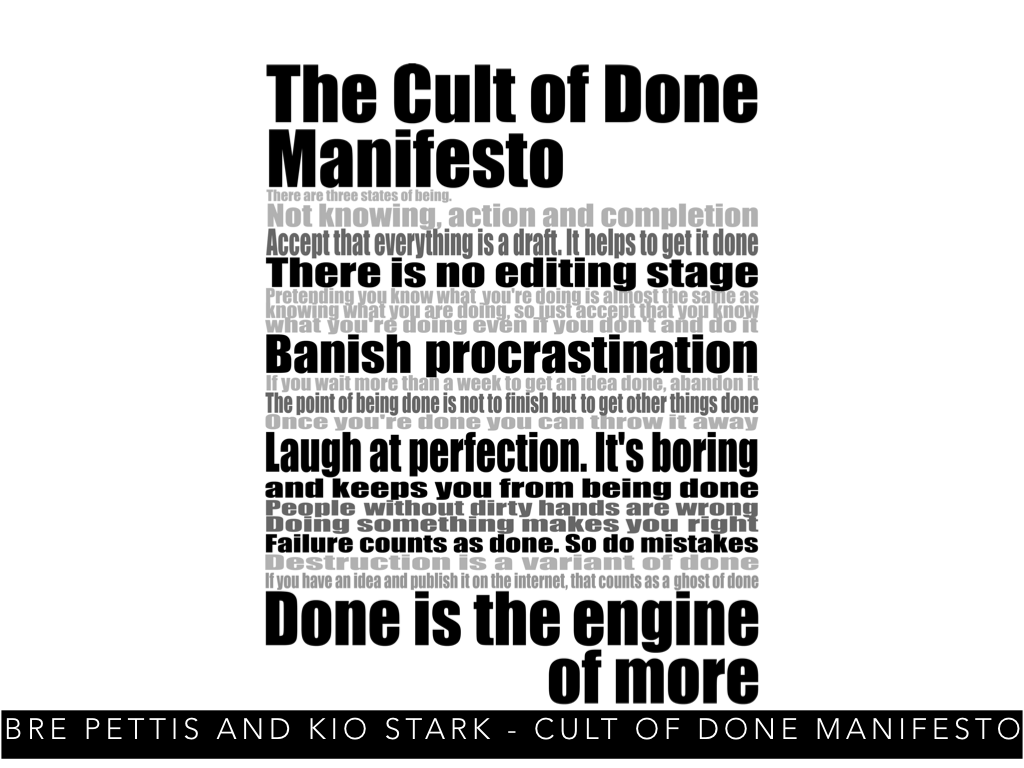

But truly – I’m here to tell you that perfectionism, while often encouraged in academia, can be a significant barrier to getting things done (and hint – also a cause of imposter syndrome). The Cult of Done Manifesto is a document I adore that gets at this point. “Accept that everything is a draft,” it reads. Your project is a draft. You’re a draft! It helps to think about ourselves as works in progress. The Cult of Done Manifesto isn’t a text that necessarily comes from the agile community per se, but they have overlapping concerns. Iteration is a part of our practice. It’s how we learn.

It’s worth considering that not everyone is equally able to iterate or develop in public – women, people of color, and other marginalized communities have different experiences of the world and of digital life. And the internet, the public audience for much digital work, is toxic. But it’s worth at least thinking about how you can push yourself to rethink the practices with which you’re comfortable in spaces that allow you to do so. I’m not really talking about a binary, where, on the one hand, things are kept fully private until they are absolutely perfect and, on the other, you’re publishing every piece of half-finished work for all to see. Find what makes sense to you. Consider how you can take small steps that work for you in the direction of being more comfortable with your work in progress as something worth sharing.

One last note on agile. The agile community released a series of principles that are worth pausing over. I’ll read them. Individuals and interactions over processes and tools. Working software over comprehensive documentation. Customer collaboration over contract negotiation. Responding to change over following a plan. Keep in mind that these come from the software world. Let’s take a moment to think about them. What do you notice about them? How might these apply to your own work as a humanities student? As a DH student? What are they missing?

[Sidebar: At this point I paused for discussion and questions. My goal was to get the students to think about questions of communication, self-reflection, and iteration as they might pertain to their own work. The students had great thoughts and questions about how to apply agile thinking to digital projects and dissertations. One that stuck out to me - how could you apply these sorts of ideas to a project where you were, really, the sole person working on the project? I suggested in response that, first, you could project manage yourself in the same way you would a team and that, second, projects were almost always the product of many hands, even if they might appear to be the work of a solo individual. Think deeply about the help you might be overlooking and how you can better structure those relationships.]

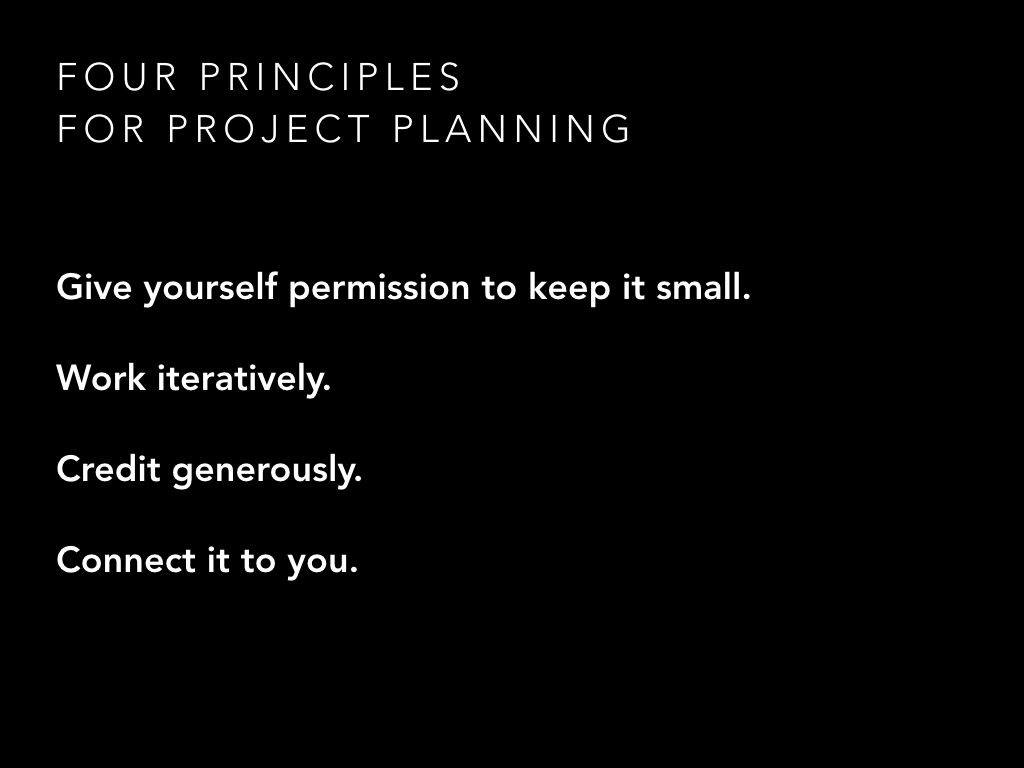

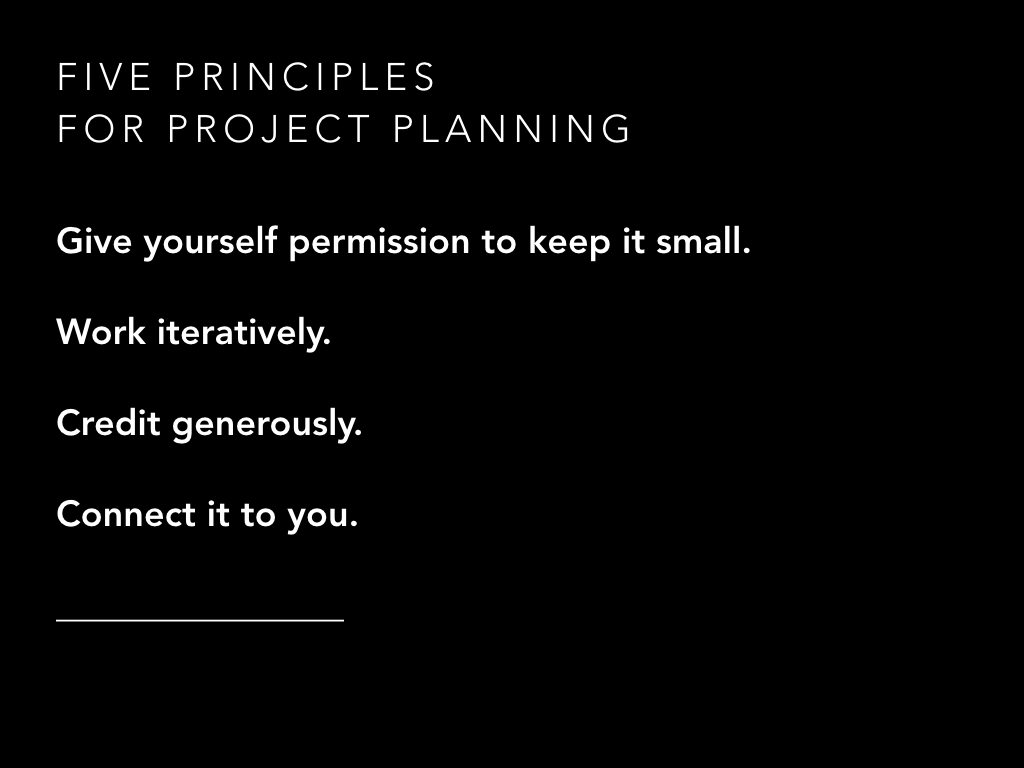

Lists of principles like this are often helpful, so here is my own spin on the conversation. If I had to offer four principles for DH project planning, I might offer these. Give yourself permission to keep it small. Work iteratively. Credit generously. Connect it to you. There could be many others, and I might give you a different list depending on the day of the week. But they’re a start. We’ll talk more about what some of these points mean shortly.

Everything we’ve talked about so far could be filed under the question of how you’ll do your work. But, at this early stage, you’re probably also thinking about - obsessing about - the what. What exactly do I want to do with this project? One project management tip: this can be a dangerous question. For humanities students and faculty, it’s all too common to want your idea to go deeper, further, more complex. You’re trained to deconstruct and push ideas. This is great when writing a book or teaching a class. But in a digital project each of these potential ideas represents time and energy on your part. Digital projects aren’t developed at the speed of an idea or the speed of writing. They take time to implement. And each new idea takes more time.

Instead, I want to suggest you think about a related question as enlivening.

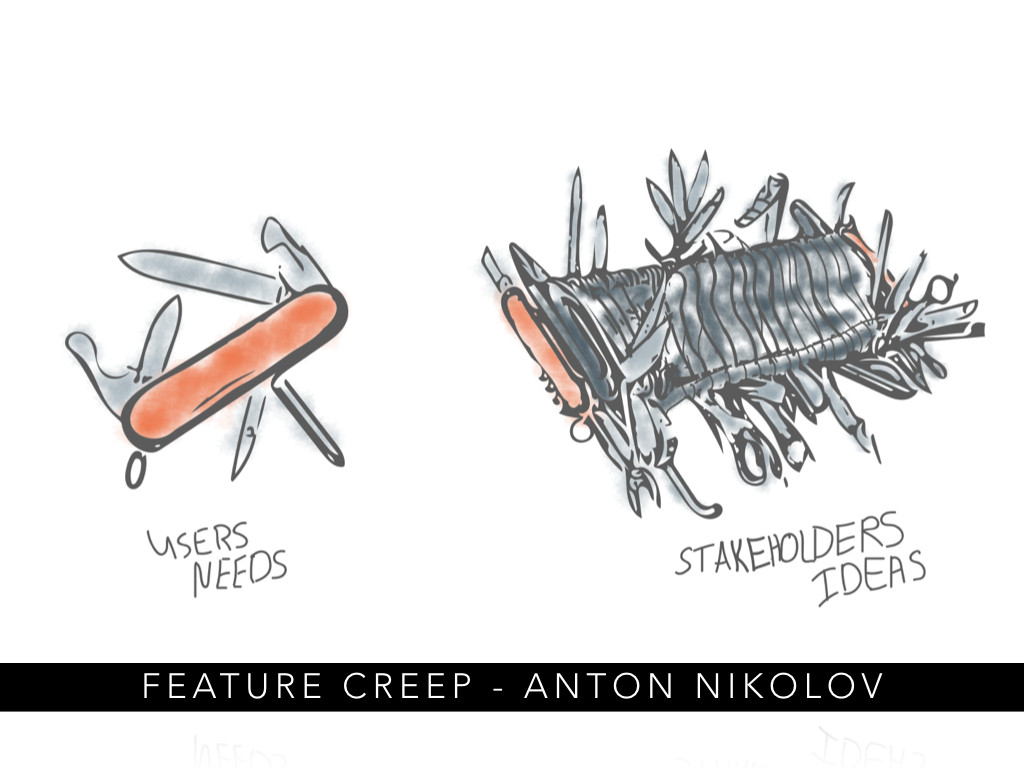

Instead of asking, “what do I want to do?” you might ask, “what don’t I want to do?” It’s a powerful question. But it is very, very hard to ask it of yourself. And it’s a question whose value only becomes clear with experience. You learn the value of it the hard way. Put another way - check out this image.

Feature creep refers to a tendency for projects to creep along, growing in size, way beyond their original intention. And at a certain point, like this tool here, a project becomes unwieldy and useless. You can’t even pick it up without stabbing yourself. We’ve all worked with tools or interfaces like this – so many options that you can’t do anything at all. When you continue to layer more and more ideas, more and more features, onto a project, things can quickly spin out of control.

This is an especially difficult problem for students of digital humanities because they’re often coming to these questions for the first time. So you don’t know if an idea is a reasonable one or totally impossible. Spoiler alert - this a problem even among professionals. We’re all dealing with this all the time. So I wanted to give you a few ways to think about scoping out features.

[Sidebar: I believe I made a joke here about Pepper’s reaction to feature creep.]

I wanted to share two quotes from a conversation we had about project scoping during my time as a student in the Scholars’ Lab. Apologies if I don’t get the exact wording right - this was a decade ago after all. Here is Wayne Graham, former Head of R&D in the Scholars’ Lab, discussing how he plans out work on a project. He takes any estimate his staff gives him and multiplies by pi, because things always take longer than anticipated, even for professionals.

Now, here is a quote from Bethany Nowviskie, former Head of the Scholars’ Lab and Wayne’s boss.

“I take whatever estimate Wayne gives me and double it.” It was a conversation that really stuck with me. Multiply any estimate for how long a project or task will take by two pi. That’s a lot longer than expected!

How, then, can you decide what’s worth doing? In the face of these kinds of difficulties, it’s helpful to have some sort of a system in place for determining the value of what you’re thinking about doing. This is especially helpful in humanities work, where sometimes the features we’re talking about directly build upon our own ideas about things we care about. It can all feel very personal. It can be helpful to try to make things objective. Here’s one way to do so.

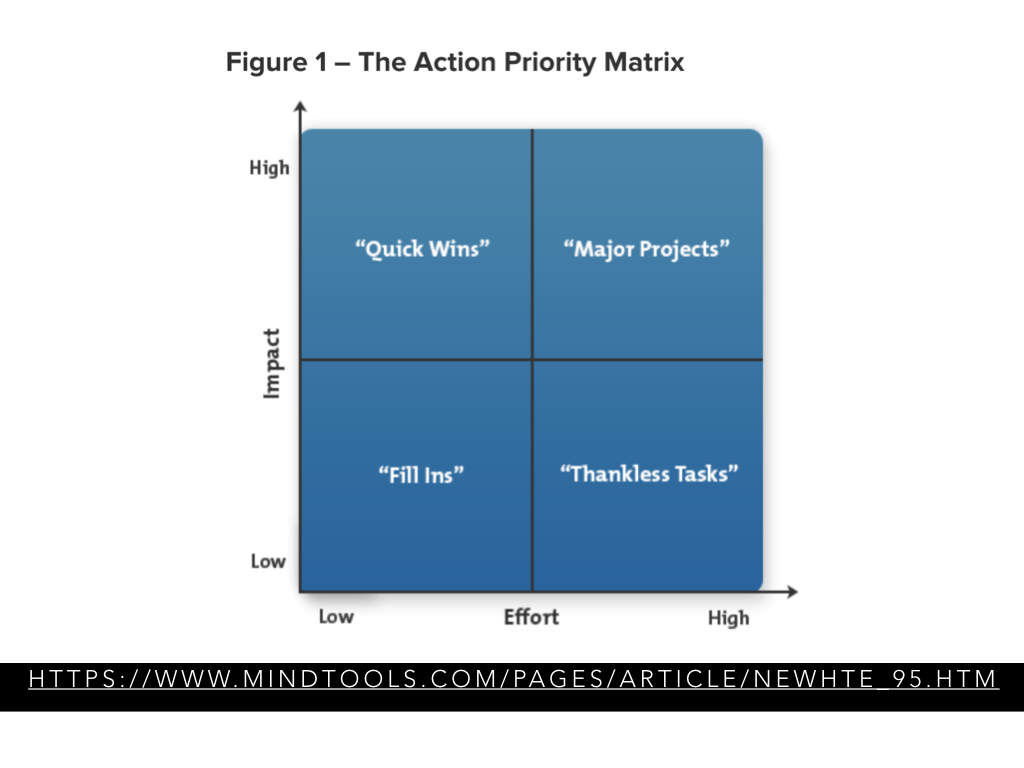

Here’s a checklist for you as you go about your work. Is this feature hard? And is it important? These questions are difficult to answer when starting out, so it can be good to ask for help as you think through them. But it’s also a skill that you can develop with experience. So take the time to try to break your large project into as many components as possible.

Let’s practice together. Take the idea of a digital archive. That’s a big thing. But you could poke at a lot of pieces of it. Say…you were going to make an archive of American protest. What are some decisions you would have to make about it? What would some features be?

[Sidebar: had we more time, at this point I would have paused to actually run the speculative exercise for designing a digital archive, something I’ve done in courses before. I was watching the clock, though, and felt I needed to just give a few conceptual takeaways before moving on. I asked the students to consider a range of different questions that would impact the features and scale of such an archive. Will the archive be private or public? Will it index everything about the topic from all countries in all years? Maybe just one year? Maybe just one country? All types of media? Maybe just text? Will people be able to add to it? If they can add to it, will you have to moderate their contributions? The answers to all of these questions will affect the scale of a project and the time it will take to implement.]

You quickly begin to see that there are many different ways you can slice up a big idea. And any one of these decisions could potentially blow your project up and make it unwieldy. Start small, and, remember – a project that is all things for all people is probably nothing for no one.

That checklist I gave you before is actually a pretty common one, and this visualization probably seems like common sense. But I still think it’s powerful to see laid out like this. Take a moment to look at it. [Sidebar: pause for a moment] Where do you think you want to live? [Sidebar: the answer is top left] Where do you want to avoid? [Sidebar: the answer is bottom right.] And of course you will probably spend most of your time in the top right. Not too difficult to tell that because this visualization gives you helpful names for each category.

This sort of task-oriented thinking isn’t something we’re used to doing. But it’s helpful to think about your work this way. Even something as abstract as writing can benefit from this! In my own situation – I’m a full-time, 12-month, 40-hour staff person, but I still try to write, publish, and (as you can see) give talks. Trying to finish writing projects when you have the regular standing commitments of a job is difficult. I only have so many hours in the workweek. Methods like these help me to figure out how long I have to write, what I can accomplish, and what I can’t.

[Sidebar: I want to give huge credit to Ronda Grizzle here for everything she does for the Lab related to project management. Everything I know about it I learned from her. Anandi also had wonderful thoughts on project management during this portion of the workshop, and she shared them with the students.]

One last quote on this that I want to leave you with. “Perfection is achieved not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.” Saying no is a super power. Truly. I’ve said in the Scholars’ Lab before that the best projects – the best features – are the ones you don’t implement. Because saying no to something in the short-term means that, in the long-term, you can say yes to something you really want to do.

[Sidebar: I set aside time here, again, for any questions or discussion that might come up.]

The next question is a big one for students. What kind of support do you have? It’s one thing to talk about the difficulties of project development in theory, but it’s another to come up against the actual realities of project development. You all have lives. You have programs you’re trying to do. This is hard. But the good news is that you’re not alone.

[Sidebar: Pepper being supported, cats, etc. etc. It was also about this time that Sarah and I agreed we would not get to the follow-up activities I had planned. Instead, the new plan was to finish out the talk portion, discuss with the students, and describe the kinds of activities we would have done with more time so that they could follow up with them on their own later. This revised plan meant that I didn’t feel the need to rush through the material - I could instead allow the students space for discussion as they wished.]

For one, I wanted to point you a blog post put out by the MLA Committee on Information Technology on how to begin thinking about putting together a digital dissertation. There are a number of good resources linked here that I would encourage you to check out. Guidelines for evaluating digital work. Models of work that has already been done. Any difficulties you might face from the standpoints of project development, of getting buy-in from your committee, or of dealing with the university have probably been faced by others before you. It is highly unlikely you are the first ones to have these issues. So look for evidence, help, support, and resources from the larger community. I’m happy to help you find things as well. Feel free to reach out.

I’m also certain there are people locally – students, staff, librarians, and faculty – who are in your corner. Sarah has already told me about some of them, and you already mentioned others in your introductions. Accept their help - you don’t have to do this alone. But be careful you don’t take exploit their goodwill.

Instead, I would encourage you to think of this work as an opportunity to start to develop a space more like what you would want the academy to be. This is an image of the Collaborators Bill of Rights. Digital work takes many hands. Consider that labor. Share generously. Credit liberally. Make sure that everyone all the way down is acknowledged in your project, in as many places as you can. Consider how you can make these people your true collaborators if they are up for it – ask them how they want to be cited. If their voice and work are important to you and your project, ask them if they want to co-present or co-author with you. These things might seem weird, trained as we are in the humanities to think of authorship as something done by sole individuals, but that doesn’t have to be the norm. And I can assure you that these conversations mean the world to people in libraries.

This conversation is not just about projects. It’s about people. And you can use this space to begin to help shape a more expansive, generous, and humane way of doing digital work. In the Scholars’ Lab, for example, we push for real collaborations. We do work with – not for – as much as we can. So begin to think about how your project, in some small way, can begin to flatten the hierarchies at work in the academy. If you were interested in a related document about rights you should expect of collaborations as a student, I’d also point you to the Student Collaborators Bill of Rights from UCLA.

[Sidebar: I paused again for questions.]

One tool we use in the Scholars’ Lab to help structure relationships in positive, ethical ways is called a charter. The charter is the last concept that I wanted to introduce to you all. It’s a pretty simple idea – a charter is a document that reflects your shared values and principles. What you expect of each other, how you’re going to work together. What you hope to get out of the thing. Think of it like a personal and collective mission statement.

A charter is something that a group can return to later when questions come up. Articulating values like this can be really useful because when the rubber hits the road you can ask of any new feature, project, or idea - does this connect with the things I care about? Is it advancing our mission, or at least our mission as we want to see it? In front of you is the charter for our first Praxis cohort. We’ve had students on this collaborative fellowship put a charter together every year, and we have several for the lab as well – one for the lab in general and another for how we approach student programs.

The reason I end with the charter is that it connects to what I might offer as a last principle for project planning.

A project is only as good as it connects to you. But you have to decide what that connection looks like.

We encourage our students to think about charters as an opportunity to articulate their project goals and also their goals for their own portion of the project. Their goals for themselves. What do they hope to gain? How do they hope to grow? What do they acknowledge as their own limitations? A project should, in some way, help you in your life. It’s going to get you to a place you want to be, be that professionally, spiritually, intellectually, or ethically. I thought of my dissertation as a story that I wanted to sit with and a story I wanted to tell for a few years. This is similar to how my colleague Jeremy Boggs describes digital archives and digital projects more generally. To him, projects tell stories. Put another way, how is your project going to help you tell yours? Or more specifically – what kind of person do you want to be? How can the telling of your project’s story help you to bring that person into reality? One answer might be as simple as “this content is important to me.” Another could be “I want to become closely connected with the librarians I work with and learn about their lives.” It could mean that you’re aware of the climate of the academic job market, and you’re using this as an opportunity to develop skills and expertise that can help you in a wide variety of careers.

A project is more than just the stuff - the disciplinary material - in it. It’s a statement about how you view your work and the world and how you think each should be. That’s why there’s a blank line at the end here. You have to decide what that last line is for yourself.

To tip my own hand a little bit, I wanted to speak just for a moment about how I see my pedagogical work and the project underlying it. I had this quote by Paulo Freire in mind as I was writing this talk. “As beings programmed for learning and who need tomorrow as fish need water, men and women become robbed beings if they are denied their conditions of participants in the production of tomorrow.” Sean Michael Morris shared this quote with us at Digital Pedagogy Lab a few weeks ago, and it’s been on my mind ever since. There is a lot there, but Freire is getting at a few things. For Freire, education should always be a radical act of revolution. Students should always be thoroughly engaged in the process of shaping their own learning experiences, and it is the job of the progressive educator to help them overturn traditional modes of education and allow them to act as teachers themselves. The quote is about what does or does not help students produce their own tomorrows, but it’s also about producing the tomorrows of education and society.

I try to approach all the projects I work on – and really the students are the projects – with a sense of this animating philosophy in mind. I always want to ask, “how is what I’m doing here empowering students to reshape the structures that are holding them back?” There can and should be a reason for everything that I do, and I’m constantly thinking about what that reason is.

That’s where I’m coming from. That’s how I fill in that empty line. And I want you to think about that why question for yourselves. It’s not just a why for the content. But also about the why behind all the steps of project planning. How can your work help engineer the tomorrow you want to see?

So I want to end today by helping each of you engage in some soul searching. With the time we have remaining, we’re going to run a series of exercises and discussions about the kinds of goals and assumptions you’re bringing to this. And we’ll talk things out – I’m happy to spend more time addressing specific questions as well. We can go anywhere you want. Let’s get started.

[Sidebar: as I mentioned above, we didn’t actually have time to run the workshop proper, and we instead used the remaining moments for more discussion. I shared the slides with the folks who invited me, because they thought they might make for useful follow-up activities throughout the year. So even though we didn’t get to them, I thought I’d share the materials below with a few quick notes on what I had in mind. I’ll quit with the brackets, as the talk proper has ended. What follows is all just framing for the extra material I had prepared.]

Workshop Activities to Get You There

The preceding talk and discussion aimed to get the students thinking about their projects from a number of different angles - practical, logistical, collaborative, and theoretical. But I ended with values because, to me, they’re the most important. They can also be the most difficult to think about. It takes practice to learn how to articulate your values and goals in relation to a project, a measure of self-reflection that we aren’t necessarily taught how to do in graduate school. The following activities are meant to build on each other and guide participants towards a firmer sense of themselves in relation to their projects.

I also want to explicitly note the importance of the work of two people to the shape of these activities. Ronda Grizzle is the expert in the Lab on project management, charters, and life design, and I adapted the mind mapping activity, in particular, from work she has had us do internally. Secondly, I attended Digital Pedagogy Lab over the summer, and Sean Michael Morris’s breakout session on writing about teaching was instrumental in changing how I thought about in-class writing activities. I learned the four rules for writing from him in that session.

There are three activities I had planned. Given the title of the talk, I suppose I might call them “three activities to get you there”:

- Charter discussion

- Mind mapping

- Timed writing on values

I’ll contextualize each activity briefly and share the slides that I had prepped. Hopefully that will give a sense of how I’d run them if others are interested.

Charter Discussion

Charters can be somewhat difficult to wrap your head around without models. So I planned to begin by offering the students some examples drawn from past years of the Praxis program. I shared the link for praxis.scholarslab.org/charter with the students, and from there I planned on doing a pretty typical think-pair-share activity. None of the charters are especially long, and it’s not necessary to read through one in its entirety to get the flavor of the piece. I anticipated having each student pick a charter to spend five minutes reading and thinking about. After the initial thinking time, they would spend five minutes discussing with their neighbor before we came back for a general discussion for ten minutes or so. The goal was to give the students models and to show them the kinds of categories that might go into such a document. Hopefully from there they would start thinking about personal, professional, and technical values they might have alongside their goals for the year.

The relevant slide:

Mind Mapping

After looking at charters from other groups, the students are ready to start thinking more deeply about their own views on things. For that, I turn to mind mapping.

Mind mapping is an activity that asks people to free associate words related to a particular topic in in the service of opening up a free, non-judgmental space for brainstorming. The first challenge with mind mapping, I find, is that people don’t necessarily know what it is. So several of the following slides focus on setting up the concept for participants.

The definition and example mind map I offer here come from a book Ronda Grizzle shared with me called Designing Your Life by Bill Burnett and Dave Evans. After offering a definition, I describe the general process, which involves a starting word, mapping out associations to that word, and then mapping out further secondary associations from there.

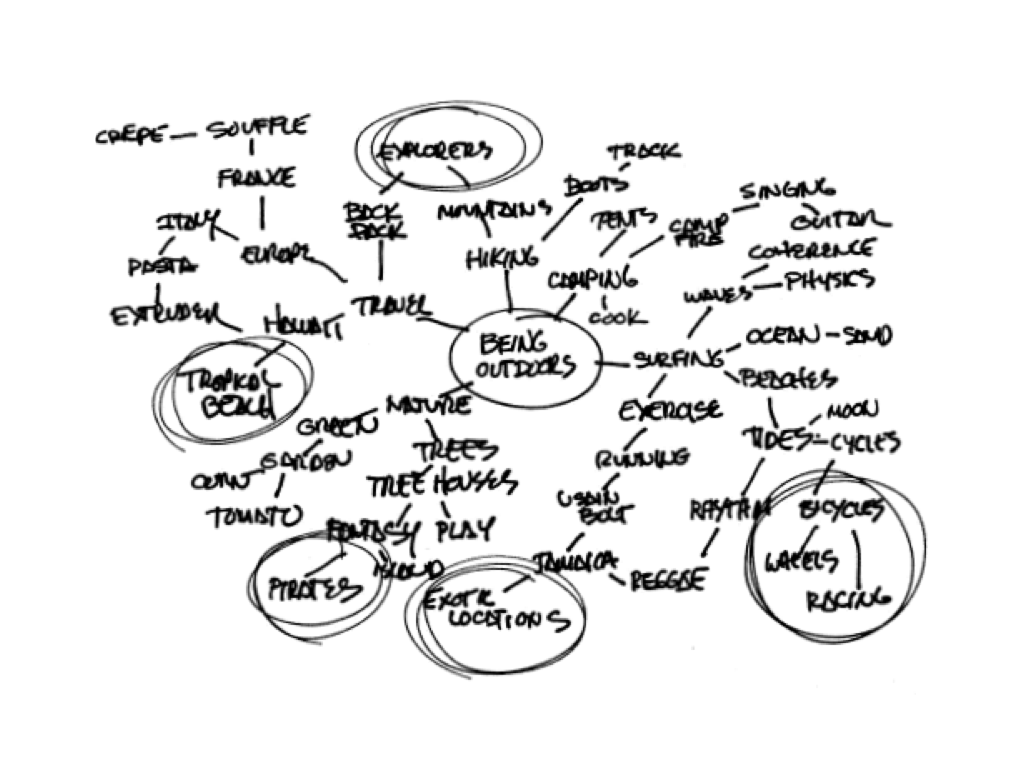

Images help to explain this better, I think, so I offer a picture of an example mind map from Designing Your Life, where someone is trying to brainstorm a potential career from things that interest them.

Next I suggest some reasons for mind mapping. By getting all of your ideas on the table, the process allows you to reflect more fully about which pieces are important to you. At the end of the mapping process, circling four or five of the words most important for you will help clarify which elements could be the basis for a good charter.

The starting word in the center of the map is important, as it generates the other associations for you. So I planned on reiterating the questions that we discussed in the course of discussion to help the students get started and to help generate other associations.

From there, the mind mapping activity involves the following:

- Placing your starting word.

- Mapping outwards for five minutes.

- Reflecting on the resultant map for five minutes and circling important concepts.

- Discussing with their neighbor for five minutes.

I’ve done a version of this activity for helping people develop a sense of their DH pedagogy, and I’ve found that mind mapping is great for helping participants engage in deeper forms of self-reflection about their everyday practices.

Timed Writing on Values

Now that the students have seen some examples and discussed them, it’s time for them to write. They’ll be in a decent place to do so, hopefully, because the mind mapping activity already asked them to think about large topics that were meaningful to them. As writing about values can sometimes feel frightening, I drew in Sean Michael Morris’s great rules for timed writing prompts here to help encourage the participants. I chose eight minutes, but you could give a longer amount of time - anything would be useful. After writing, I could imagine having a productive conversation about the results. The students need not feel pressured to share their exact wording, but a general discussion of the process, the issues, and things that they gravitated towards would be useful.

That’s it for the workshop and accompanying materials! Happy to talk with anyone who might be interested in working with them. The trip to Emory was very invigorating and provocative, and I was endlessly impressed, especially, by the students at ECDS. They’re a great crew. Keep an eye out for them - they’re already doing important work, and you’ll be hearing from them soon.