Praxis and Scale: On The Virtue of Small

15 Jun 2018 Posted in:digital humanities talks pedagogy scholars lab dh now The following is a version of my talk for DH2018 that will be given as a part of a roundtable on Digital Humanities Pedagogy and Praxis. Participants on the panel responded to a CFP marking five years since we launched the Praxis Network.

I am Brandon Walsh, the Head of Graduate Programs at the Scholars’ Lab in the University of Virginia Library in the United States. Today I want to talk about a tension I see in DH pedagogy between the hands-on, student-driven instruction that we’re discussing here as part of the Praxis Network and the scale at which we can offer it. Can we take what started small and scale it up in an ethical and informed way? In particular, I want to suggest that “small” investments in pedagogy driven by students are worth it, that we should resist uncritical calls to scale up the reach of our praxis, and that we can best measure the growth of our programs by the degree to which our students are empowered to become engaged, generous teachers in their own right.

My own local context for this talk is the Scholars’ Lab’s Praxis Program, which offers a targeted digital humanities injection during the early years of a student’s graduate work. In the Praxis Program each year, staff and faculty work alongside a student cohort to theorize a new digital intervention and to train the students to implement it themselves. We shift from a series of workshops and discussions in the fall semester to a lab model in the spring, from the staff in front of the room to all of us working together to get a thing done. Funding for the program comes from the library in the form of teaching releases for the students, and I’m happy to talk more about these practical details in the Q&A. The program aims to equip graduate students with the skills and ethos necessary to thrive when carrying out collaborative, open work that might happen on or off the tenure track, and, drawing upon the pedagogical theories of Cathy Davidson, Paolo Freire, Bethany Nowviskie, and others, we do this by putting the students in charge, allowing them as much as possible to decide what they work on and how they’ll work on it.

This panel invites us to reflect on how student programs like these have changed in the past several years, on their triumphs and difficulties. Now in its seventh year, we measure the Praxis Program’s success by a number of metrics - exit interviews, job placements, future awards received by our alumni, and publications.

We’ve assembled a series of projects of varying shapes and sizes, conceived and developed by the students themselves and with various afterlives, and a host of alumni who have gone on to build on their time with us. But we sometimes get questions or comments about the program’s scale.

Each cohort consists of six students. Pretty small compared to a traditional course that might engage a single instructor, and, what’s more, this program draws in virtually all of our staff at one time or another. That is a significant investment of resources in a small group of students each year. Over the years we’ve been asked about the limits of the model from a number of people, inside and outside UVA. Can we have a second cohort of students each year? Could we take the model and grow it?

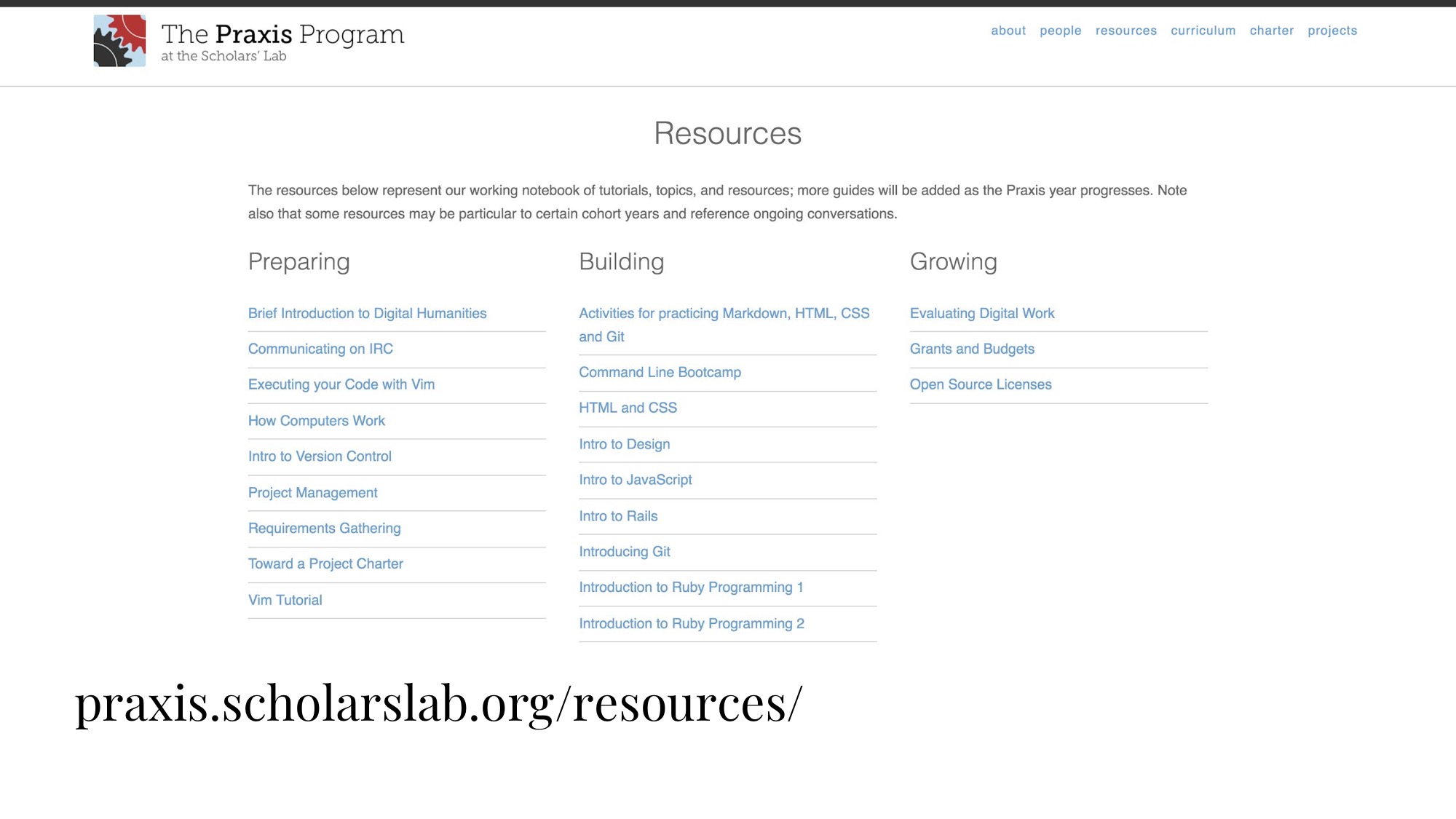

They’re reasonable asks, but they raise a number of issues for me that I hope might be useful for any student program. The first is simple – can a model like this grow? Although we have some recurring units, lessons, and resources each year, the student-driven nature of the Praxis Program requires us to embrace the unexpected. This last year, for example, we started out with one idea but reversed course and rebuilt the curriculum based on the unfolding interests of our students.

This requires a serious commitment of time and resources - it can be difficult to predict exactly which staff members will be the primary points of contact for the project, and responsibilities might change unexpectedly. There is also a question of capacity. We are limited in the number of students that we can maintain at any one time and still carry out our other obligations as a library unit. I should note here that there are powerful examples of people doing this kind of engaged student work on a large scale - the #FutureEd initiative by Davidson and others is a clear example, and instructors in the sciences are often already working at a much larger scale when they try to implement similar approaches in their lecture courses. Numbers might be part of a necessary approach to your own critically engaged pedagogy.

Another question - should it grow? Perhaps rather than expanding a single working model, resources might be better served in other areas, other programs, other people - more on that in a moment. For our group, at least, keeping a smaller program that centers project-based education is a strategic investment in the individual as a meaningful point of intervention. The core of our work, more than any digital project, is the people, who we try empower to act as DH professionals and pay their lessons forward from day one. Far from limiting our impact, I think that deliberately staying small attempts to do more with less, to invest in the futures of these students as they become teachers themselves. We believe in the grassroots impact these young people can have on the field and on their communities.

And finally - how should it grow? Most importantly, to me at least, is that we continue to develop educational experiences that are as equitable and just as possible. In my experience, conversations around scale aren’t usually met with offers for more resources. And we should not let calls to grow tempt us into uncritically adopting volunteer labor or unpaid internships. UCLA’s Student Collaborator’s Bill of Rights is a touchstone here. Students might be willing to volunteer their time with you for the sake of the experience, but our position is that we should resist those offers. There is plenty of evidence to suggest that allowing such unpaid labor reinforces socioeconomic and racial disparities in the workforce. We try not to grow beyond our ability to fund our students.

I want to pause momentarily to recognize that this is a fairly privileged conversation. The Scholars’ Lab programs are in the fortunate position to be well funded at the time of this writing, and (even at my own institution) there are many units and individual people tasked with raising programs from the ground on little to no funding. I’m sure there are some of you in the room in that same position. My colleagues and I are fortunate. Ours is not the only way to shape a program, and it’s certainly not the best one for every institutional context. I hope, however, that this conversation might offer those of you making difficult decisions about resources a model – or, at least, a series of ideas – to consider. You don’t need an extensive reach or a robust cohort of students to make something meaningful happen. If you can fund one student – that is worth doing. Embrace the fact that you can engage that one person in the important work of developing and growing your program. Do what you can with what you can, but, again, we should collectively resist calls to grow student programs beyond our capacity to resource and sustain them.

I think a lot about the disparate amounts of privilege some of our students enjoy, and much of our effort is spent trying to scale our impact in ways that broaden access even though we can’t afford a deep dive with many students. This means offering a diverse range of ways in for students, with other opportunities for engaging our community that might be more targeted and more sustainable. It also means engaging alumni of the Praxis Program in our other initiatives, folding their strengths into our pool of resources and giving them opportunities to explore themselves as teachers. We try to engage these students who have been able to access our resources, time, and knowledge in helping their colleagues who might not have benefited from the same.

Since the Praxis Program’s inception, for example, we have partnered with our campus’s version of the Leadership Alliance Mellon Initiative (LAMI) to pilot a complimentary program in DH and library research methods for undergraduates from underrepresented communities with the assistance of our Praxis alumni. The undergraduates taking part in this program are thinking about graduate school, and our contribution is to give them just a taste of what research at that level might look like for them. Our Praxis alumni lead a workshop for them, participate in discussions, and also show what the next phase of life after undergraduate can look like.

I’ve talked a bit about our past and present. A single thought on the future of our programs it would be this - I think it is incumbent upon us to turn our work outwards and think about the impact our students can have on a broader community beyond our institution - that’s where the Scholars’ Lab has been heading, and I’d like to continue in that direction. In the direction of out rather than in.

One way in which we’ve tried to do this is to work more closely with institutions in the region. We’ve partnered with Washington and Lee for a few years now to engage students as guest DH workshop leaders on their campus, and we’re soon hoping to expand to University of Richmond as well. We ask our students to blog about these workshops, and we have been accumulating a list of these resources for others to learn from or build upon. Similarly, I would like to extend the work of our students to the local Charlottesville community, something the Lab has been increasingly engaged in, but I would like us to be more deliberate about incorporating students as we do so. We can continue to empower student research but do so as part of the Lab’s mission of promoting access, sharing resources, and advancing social justice.

If I have one point today point it is this - there are limits to the number of deep dives you can take. But they can serve as excellent starting points for other schemes - you can do a lot with a little. Our former director, Bethany Nowviskie, once used the phrase “too small to fail” to describe our approach to graduate education. Small can still have a big impact. At the Scholars’ Lab, I’d like our own particular brand of small to be public, engaged, and local, empowering students who feel confident but also compelled to give back to their peers, students, and neighborhoods. Weighing ourselves in this way, by the degree to which we help to democratize and provide access to these sorts of methods, questions, and technologies ultimately feels more meaningful than doing so by the number of students we reach.

References and Further Reading

- A Student Collaborators’ Bill of Rights. University of California Los Angeles Center for Digital Humanities. https://humtech.ucla.edu/news/a-student-collaborators-bill-of-rights/

- #FutureEd. Humanities, Arts, Science, and Technology Alliance and Collaboratory. https://www.hastac.org/initiatives/futureed

- Davidson, C. (2017). The New Education: How to Revolutionize the University to Prepare Students for a World In Flux. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Nowviskie, B. (2011). “Praxis and Prism.” http://nowviskie.org/2011/praxis-and-prism/ ———. (2012). “Too Small To Fail.” http://nowviskie.org/2012/too-small-to-fail/

- Rogers, K. (2015). “Humanities Unbound: Supporting Careers and Scholarship Beyond the Tenure Track.” Digital Humanities Quarterly 9.1.

- The Praxis Program. University of Virginia Library’s Scholars’ Lab. http://praxis.scholarslab.org.

- The Praxis Network. University of Virginia Library’s Scholars’ Lab. http://praxis-network.org/.