Workshop on Reading with Command Line

27 Feb 2019 Posted in:digital humanities pedagogy dh now Crossposted to the Scholars’ Lab blog

Alison Booth and I are co-teaching a graduate course this semester on Digital Literary Studies. As a part of the course, we’re having a series of technical workshops - command line, Python, text analysis, encoding, and markup. The scheduling worked out such that these workshops wound up being on Wednesdays, with the discussions of critical theory on digital humanities and literary method mostly on Mondays. That’s all fine and good, but I worried that neatly dividing the class out in that way would create a divide between the one day of the week when the students were actively discussing the material in the course and the other when they were mostly in hands-on workshops. Rather than having a hacking day and a yacking day, I wanted to see what I could do to create an environment for hack-yacking. So when I taught the first workshop on command line, I wanted to try something slightly different from what I normally do by making more room for discussion. I wanted to bring the Monday readings and conversations back into the Wednesday workshops.

Teaching programming well is very difficult. An easy, low-hanging fruit way to get the material across to your students is to connect your laptop and type in front of the students, explaining your keystrokes as you go and asking them to mirror your actions. Another approach I’ve seen (and used) uses slides to do something similar - sharing code examples and interspersing theoretical concepts as you go. Both of those approaches are all to the good, but they feel a bit too much like lecturing to me. I was trained as a teacher of English literature, which means that my bread and butter is the seminar. My approach to the discussion seminar has always been to act as something of a void in the center of the class, asking questions that get the students to engage with the material and each other more than with me. Lecturing has its place, I’m sure, but it generally makes me uncomfortable and doesn’t reflect the kind of pedagogy I value. So when teaching this workshop on command line I wanted to push myself a little more to see how much discussion I could incorporate into a technical skills workshop. How could I use this experience to help the students begin to think about technology as something that they could engage critically with? as something that was not so alien from their normal work of thoughtful, critical discussion?

My goals for the seventy-five minute session, then, were as follows:

- Introduce the concept of the graphical user interface (GUI)

- Introduce the concept of the command line

- Give practice with the command line

- Use the command line to do something that connected with the discussion we had been having elsewhere in the course

The overriding concern for me was to communicate the technical skills the students needed while not making it a “watch what I type” workshop. I wanted discussion and engagement to be the main priority.

To start off, I shared several different images of graphical user interfaces like this one.

I began by simply asking the students to describe what they saw, framing the activity as continuous with their usual practices of analyzing prose, poetry, or photographs. In the same way that any piece of a text or image can be interpreted and described, so too can technology be subjected to the same analysis. This component of the workshop was inspired by Erin Rose Glass. When she visited the Scholars’ Lab last semester for a talk on surveillance capitalism, she asked the audience to close read the Microsoft Word interface, and I thought the move did a great job of defamiliarizing an everyday piece of technology and subjecting it to critique. In this case, I asked my students a series of questions:

- What kind of assumptions does the GUI make of its users?

- What kind of an experience does it want you to have?

- How does it structure that experience?

- What kind of audience does it have in mind?

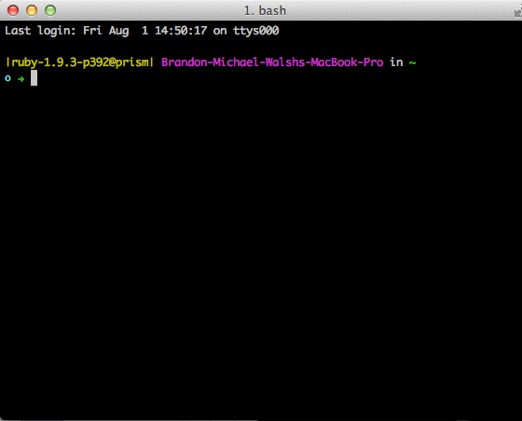

These provocations led to an interesting conversation about accessibility, design, and assumed expertise. I especially wanted the students to note how the GUI makes immediately apparent a range of options to the user. But those options are also limited. The interface sacrifices possibility for practicality, and it can never give you every possible option. This discussion set us up well for the next image I presented to them - a terminal window.

Again, I paused for discussion, asking questions that directed the students to the lack of clearly visible options in the terminal and how this suggested an assumption that its users would have a certain level of expertise. For better or for worse, it assumes that you know what you’re doing. I could have just told the students all this, of course, but I wanted them to arrive at these ideas themselves. So I mostly framed the activity with questions and helped to direct discussion, just as I would in directing close reading of a passage in a novel. In some small way, I hoped the activity would show them that the close reading and analytical skills they developed in other English classes would still be applicable here, even though the objects of study might be different and even though they might feel a bit at sea.

With some sense of what the command line was, the next phase of the workshop took the students through a variety of commands with the terminal. This component of the class felt the most like a typical introduction to the terminal in that I offered a command, executed it, and then we reflected on the results together. The commands we covered mostly focused on navigating the file system and adding or deleting files:

- cd

- ls

- pwd

- touch

- rm

- mkdir

- cp

- mv

- man

Nothing too fancy or tricky. From a practical standpoint, the students needed to get the terminal under their fingers so that they’d be prepared to work with it for the rest of the course. As preparation for this piece, we had the students work through the Command Line Crash Course from Learn Python the Hard Way. So the workshop was not their first moment experiencing the terminal, and I could review these pieces quickly before trying to engage the students further.

One easy way to try to bridge the gap between our discussions of readings and our workshop on the terminal was to drawn in one of the texts that they had read and discussed in a previous session. Superficially, this meant that the students would at least have familiar thematic material in front of them - I selected an essay for us to work with by Katherine Bode titled “The Equivalence of ‘Close’ And ‘Distant’ Reading; Or, toward a New Object for Data-Rich Literary History.” The students had been reading a cluster of essays about distant and close reading, and, for our last activity together, I wanted to defamiliarize the process of reading using the command line to further that discussion. The plan was to have our students use the terminal to “read” that article in a number of different ways. At each step along the way, we stopped to reflect on the kinds of reading enabled or inhibited by the commands.

I put the text of the article in question up on my website ahead of time so that they could easily access it. First I had the students use the curl command to copy down the text of a URL onto their computer (note that I’ve since taken this text down):

$ curl walshbr.com/materials/bode.txt

The curl command spits the text of this page onto their screen, which lead to an interesting conversation about this as a type of reading. I asked the students to characterize the kind of reading it did or did not seem to enable. For one, they noted the lack of an ability to paginate through the text, which seemed to imply that the command was meant for readers that planned to take in the text all at once. As in, curl might be meant for machines using a text as data rather than a thing to be read in a more humanistic sense.

To ensure that we all had the necessary materials, we grabbed that same text and sent it into a text file on our computer:

$ curl walshbr.com/materials/bode.txt > bode.txt

This simple command allowed us to talk about how to get web texts and pages onto your computer, gave us occasion to discuss those situations in which you would want to do so, and began a discussion about the kinds of reading possible in different interfaces for reading texts. We then moved along to a couple of different commands for getting text out of a file and onto your screen using the command line.

First, we got all of the text at once.

$ cat bode.txt

Second, we got a version that would allow us to proceed through the text page by page.

$ less bode.txt

These commands led to some good reflections on the embodied experience of paging through a physical book with your hands as opposed to using the space bar to do a similar activity. We also talked about the different kinds of reading that we might want to carry out, both in general and in digital literary studies. We don’t engage in texts the same way every time we use them, and these restrictive modes of reading foreground that. In one great moment, a student realized that he couldn’t get out of the interface created by the less command - “I can’t stop paging! I’m trapped in the text!”

From there, we used the terminal to search for particular words (the word “reading” in this case):

$ grep reading bode.txt

And then we counted the number of times a particular word occurred in our text:

$ grep reading bode.txt -c

By searching for particular words relevant to the themes of the text, we had a good discussion about the point at which characters and words on a page become meaningful. In particular, the students noticed that, for a computer, capitalization matters in a way that it does not for a human reading a document. They inferred the differences between tokens and types, the difference between any particular occurrence of a sequence of characters and that word as a unique vocabulary unit. In order to really find out how often the term “reading” appeared in the text, the students realized they would need to normalize everything by converting it to lowercase.

I’ve done workshops on the terminal in the past, but this was the first one where I tailored the commands we would be practicing to the subject-matter at hand. Besides the basics of how to interact with the file system, we really only worked with commands relevant to getting and examining textual data. The workshop helped the students come to an understanding that computers read quite literally, with no context or knowledge by default. Later on, the students would find these suspicions corroborated in a reading by Johanna Drucker on “Why Distant Reading Isn’t,” where she suggests that computational reading might be the closest reading of all. Using the terminal as a point of entry into those conversations meant that the students could find their own way to these concepts. In the future I’ll keep this sort of discipline-specific approach to teaching technical skills in mind. It worked well for making the material more immediately relevant and accessible to the students than it might have been otherwise.