The Paper Outline Challenge

21 Oct 2013 Posted in:pedagogy Update in 2023: This post originally used the four houses from Harry Potter as a theme for the exercise. In the past decade since writing this post J.K. Rowling’s public comments have become increasingly transphobic. I am not sure that anyone would find their way to Harry Potter through this old post, but I also don’t want to support her dangerous political stances. I have therefore lightly reskinned the exercise below such that it does not require the association with Rowling. I would also encourage any readers to donate to Trans Lifeline.

This teaching exercise grew directly out of a comment made by Kirk Wilkins in a recent #FYCchat. I instantly fell in love with the idea, but the semester was a bit too far along to integrate a whole new system into the course. Instead, I developed a one-off group activity in the same spirit: The Paper Outline Challenge. Group work with a twist - they competed in a tournament for a literary mug filled with candy.

When teaching a discussion section of a large literature survey that only meets once a week, talking about writing presents a constant challenge. Students are evaluated on their ability to execute writing assignments, but there is little class time in which to develop these skills and adequately address the literature. I have been working hard this semester to tie literary analysis consistently back to writing practices, and The Paper Outline Challenge attempts to do so by asking students to move from analysis to paper structuring in a very short timeframe. The exercise asks students to work in groups towards a possible paper outline in the course of a single class.

Time Breakdown:

5-10 minutes to explain the activity and read the passages aloud.

30 minutes to work in groups

10 minutes to share, declare a winner, and discuss.

Split the class into four equal groups, each of which has the same small set of passages and the same paper prompt. In the time allowed, each group must develop a paper outline: a thesis statement and three supporting points that will draw upon close readings of the passages. At the end of 30 minutes, students nominate one student from their group to read their thesis and describe the structure of their group’s proposed paper outline. The instructor then gives very quick feedback on each group’s work and selects a “winner” - the outline most likely to lead a successfully executive argument.

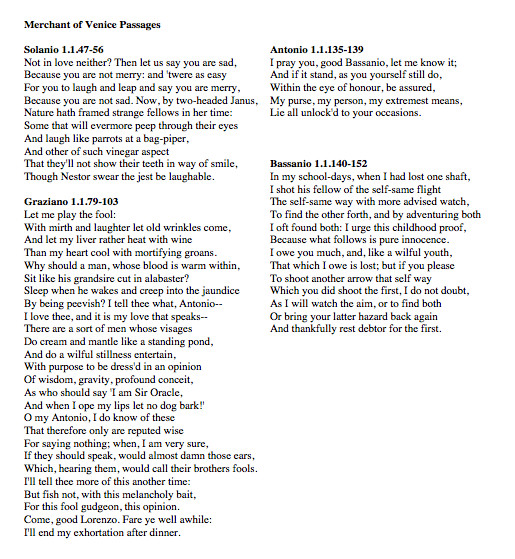

The exercise works best if things are kept as constrained as possible: common passages and a common paper prompt. The activity encourages aggressive time management, and too many options will likely detract from the students’ ability to complete the exercise. I am currently teaching a course on Shakespeare’s Histories and Comedies, so my passages all drew from a very small portion of Act I Scene I of Merchant of Venice . For a prompt I asked that students develop a paper broadly related to friendship, sexuality, marriage, or desire in some way. I chose passages that offer up opportunities for analysis and clear readings: the selections I chose had a strong homoerotic subtext, and several of the student groups picked up on this.

. For a prompt I asked that students develop a paper broadly related to friendship, sexuality, marriage, or desire in some way. I chose passages that offer up opportunities for analysis and clear readings: the selections I chose had a strong homoerotic subtext, and several of the student groups picked up on this.

The whole activity is quite frantic in 50 minutes, but it can still work well, so long as you help the students keep a close watch on the time. Ideally, it would be a 75-minute activity, allowing more time for reflection at the end and discussion. I chose to err on the side of not giving enough for follow up discussion of the event: I generally give a short email follow up to each class meeting, so I used this e-space to share more thoughts on why we did the activity and what to take away from it. I would recommend doing the same, even if this is not your usual practice.

The exercise works especially well when conducted after students have already received feedback on written work and in dialogue with those paper comments. Written feedback from the instructor is essential to a student’s growth, but the ultimate aim is for students to internalize the critical attention so that they can revise their writing on their own. To facilitate this while framing the activity, speak in terms they recognize from your feedback on their papers when discussing how you will judge the final products. I required the theses to be written out because we had stressed the importance of a well-articulated thesis statement with specific language in earlier discussions. I encouraged students to consider alternative paper structures, to consider whether their work was an observation or an argument, and to ask whether their argument was fundamentally interesting or based on plot summary. Many of the group discussions took on aspects of these questions as they shaped their papers.

Teaching detachment from one’s own writing can be very difficult. Some things just need to be cut, but we often feel personally invested in the words we put on the page. The Paper Outline Challenge also allows students to shape a paper outline in which they have little investment. The activity has no grade repercussions beyond participation, allowing students to shape ideas in a collaborative space that models the benefits for developing such detachment. Students have nothing to lose but candy, but what they stand to gain from hearing their peers and themselves speak in the language of good, critical writing - magical.