Lessons From The Lab: Designing Community-Forward Spaces

14 Apr 2023 Posted in:pedagogy talks digital humanities collaboration scholars lab Crossposted to the Scholars’ Lab blog and to Amanda’s blog.

SLab’s Amanda Visconti and Brandon Walsh recently gave an invited talk for the University of Chicago’s Library Futures series. What follows is a lightly edited version of that talk; the context was a largely librarian audience, and UChicago’s Center for Digital Scholarship moving into a new phase.

Amanda

Good afternoon! Today we’ll start off by telling you about what Scholars’ Lab is and does, before going into more depth around a couple practices we find especially effective in nurturing digital and other scholarship that takes new and experimental approaches to learning. You can visit this talk like GDoc for any resources we mention in our talk, or if you’d like a rough text version of what we’ll be saying to help follow along. Thank you!

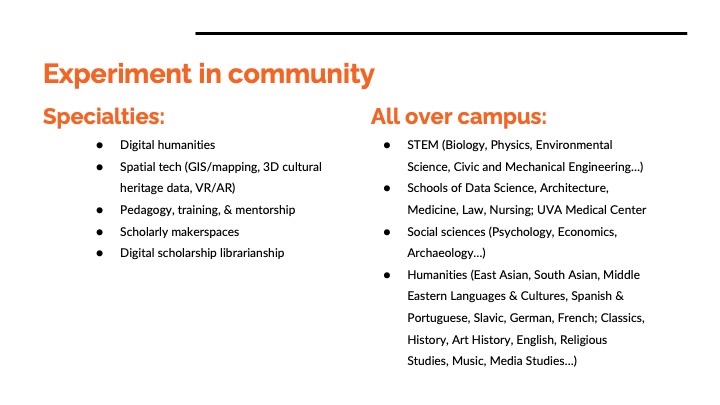

The Scholars’ Lab is the University of Virginia Library’s community lab for experimental practice in, and critical exploration of, technology and its scholarly interventions. SLab specializes in experimental, creative, and digital approaches to the humanistic research questions that are found in all fields of study. Since everyone has research questions informed by humanities areas including history, ethics, how we tell and understand stories, creativity and performance, we work with folks everywhere on campus including our medical center, and we also have a strong digital humanities (or “DH”) audience.

Scholars’ Lab was founded in 2006 (17 years ago!) and has a long history of work in the digital humanities. What is DH? You can visit whatisdigitalhumanities.com to see over 800 definitions! A quick one is that DH work asks humanities research questions using tech, and asks humanities research questions about tech.

For example, humanities using tech could look like using digital mapping and coding to take print historical real estate documents and trace where and who was impacted by racist redlining, and how that’s reflected in the geography of our city today.

One example of humanities questions about tech is looking at the biases inherent in what machine learning tools were trained on. Past SLab Fellow Ethan Reed worked with Brandon Walsh to use a tool for finding patterns of emotional sentiment in large amounts of text. His large amount of text was Black Arts Movement poetry, and it turned out that the training dataset underlying the tool he explored was Rotten Tomato movie reviews, so he spent some time looking at what kind of biases that could introduce in how the code determined what words meant what emotions.

As a founding member of the international organization of DH centers Centernet, we’re kind of auto-defined as a digital humanities (or “DH”) center, from being involved in early discussions and definitions of what DH centers could look like, then serving as a model for many more recently-started centers.

We are an internationally recognized research center and scholarly team, with alumni who’ve gone off to found DH centers and nodes of their own elsewhere. Our staff hold elected and appointed leadership and service positions in national and international scholarly orgs and editorial boards. We’re often cited as a model for digital scholarship initiatives; our lab is asked to do informal advising meetings or formal external reviews for other universities around the world interested in digital scholarship, around once a month on average.

(Amanda editing to add: I am uncomfortable being like “hey! we’re great!” in a way that might imply others are not, or that these are the activties or significers that matter most. But since how we approach things is sometimes different from other research centers, I do think it helps to know how long we’ve been doing things this way, that we’re not disadvantaged by our approach, etc.)

We are part of UVA’s Library. We have a large area with private offices and public spaces in UVA’s main library building, which is just finishing a multi-year renovation this coming fall—so we’d be happy to chat more about your own renovations.

We do a lot of things, as the result of organic growth over 17 years. This fits our current campus needs well, but can be hard to squeeze into 1 phrase! One attempt at doing so is that we “experiment in community”. SLab offers teaching, mentoring, research project collaboration, and safe physical and virtual spaces for anyone curious about learning to push disciplinary and methodological boundaries through new approaches. We’re foremost a space and community for learning together by trying new ways of approaching your interests. As I’ll discuss later, that “learning” can mean research, teaching, coding, making, documentation, data curation—many ways of knowledge-making. And the “learning together” means advocating for social justice and care, to get closer to the conditions that would allow anyone to participate in our knowledge-building who wants to.

What SLab focuses on in practice is an always-evolving mix of what current UVA faculty and students are interested in, and directions we see academic and library futures going (or directions toward which we’re trying to lead academic and library fields).

The backgrounds, skills, and evolving interests of our staff also have a big impact on our main research themes. The lab’s existed for 17 years, so by now we have a good sense of the core abilities we need to keep staffed to do well by our community—broad areas like web development and programming for text and data analysis, making and prototyping, 2D and 3D spatial study, digital pedagogy.

Our strengths include:

- GIS, mapping, & other spatial technologies

- research makerspaces and making as humanities scholarship

- cultural heritage informatics (including photogrammetry and scanning of artifacts and historic architecture; and modeling and exploring approaches to this data in virtual and augmented reality)

- Pedagogy, training, & mentorship in DH and spatial tech

- DH research & development (such as programming and design)

- Librarianship for digital scholarship

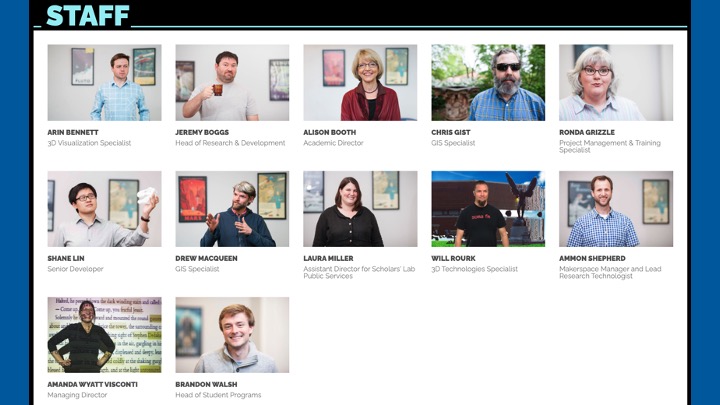

Our core resource is 11 full-time library staff who bring expertise in all these areas to scholarly collaborations with our university and local community.

We’ve found it effective to strive for as flat a organizational structure as possible, trusting and expecting each staffer to lead and influence our trajectory from their area of disciplinary and methodological expertise.

A group of five leads work when leaders and advocates are needed: I codirect the lab in partnership with English Professor and Academic Director Alison Booth, and we’re joined by Brandon as Head of Student Programs, Laura Miller as Assistant Director for SLab’s Public Services, and Jeremy Boggs as Head of Research and Development. We also have loose “units” for times when areas of work overlap: for example, our GIS Specialists, 3D Tech expert, and VR/AR expert chose to gather as a Spatial Technologies unit to help them notice opportunities to collaborate with one another, and share useful info among the group about past experiences with the same or relevant projects, tools, and people.

We don’t each cover all of these topical areas, and we routinely collaborate with UVA Library experts outside the lab who do overlapping or adjacent work around areas like digital media production and research data. But each of SLab’s staff roles do include the same two areas of work. There are pros and cons to this, but rather than e.g. having some staff who keep their head down coding and don’t work directly with faculty and students, all of our staff practice public-facing librarianship: consultation, class visits, training and career mentorship, teaching (including for credit) in the staffers’ areas of expertise. And second, all our staff are also tasked with staying up to date on, identifying, and/or setting trends in technical, academic, and library fields to prepare for and advise on coming UVA faculty/student needs—including through self-initiated scholarly learning and publication of their own.

I can shorthand “what does SLab’s daily work look like?” with three Cs: consultation, collaboration, and community building. We do a ton of short-term consultations on DH, mapping, 3D/VR and makerspace projects, and other methods open to all, on the library reference model. These can include helping someone:

- get started practicing experimental methods including digital humanities or spatial technologies, e.g. connecting you to resources for self-teaching and our scholarly networks at UVA and internationally

- conceptualize and scope a digital research project; or review your ongoing work, such as critiquing your design and code

- create or find, manage, and analyze data

- use our GIS software, virtual/augmented reality equipment, or humanities makerspace

We do longer-term collaborations with students, researchers, or instructors interested in integrating experimental or digital approaches into their research projects or teaching, or with folks who have existing digital research that would benefit from peer collaborators and mentors (e.g. paired programming). And we purposefully attend to our scholarly community to help it flourish—I’ll say more about how and why later in this talk.

A significant number of our collaborations are with students. In years when we haven’t had a dual pandemic and building renovation, we have around 65 students per year in named roles like fellowships and internships, giving us a core of folks regularly around the lab beyond our staff and folks who join us via other entry points like consultations and attending our events. Supporting the next generation of DH and experimental scholarship practitioners is a major piece of our mission. I’ll turn you over now to our Head of Student Programs Brandon to tell you more about that.

Brandon

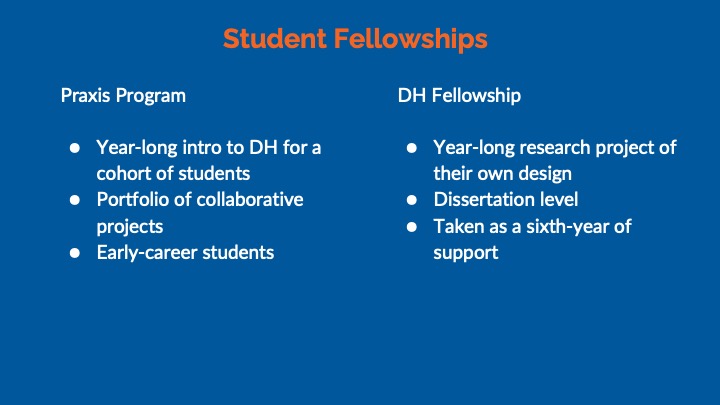

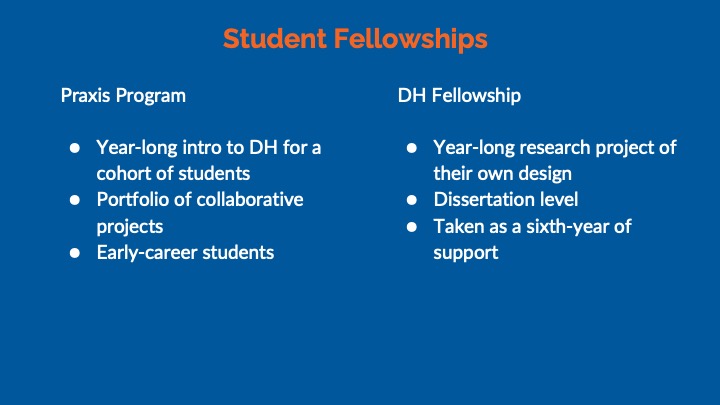

Thank you. As Amanda mentioned, the Lab offers a range of student programming. We’re perhaps best known for our pair of yearlong fellowships for graduate students, so I’ll start and focus there. Each of these fellowships caters to a different stage of a student’s time to degree.

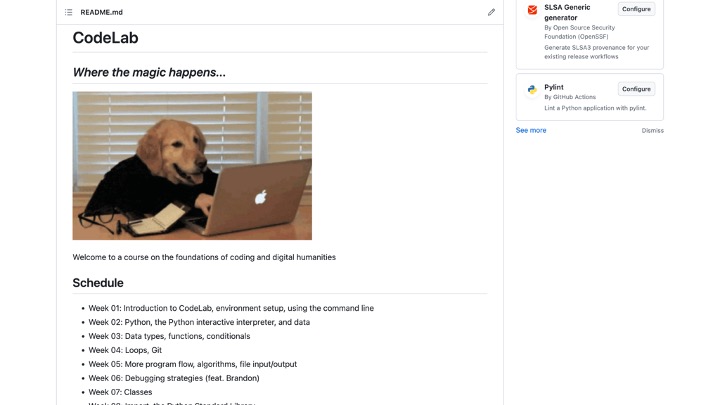

For students newer to Digital Humanities, the Praxis Program is a zero-to-sixty, soup -to-nuts crash course in DH by way of project-based pedagogy. We take an interdisciplinary cohort of students and run them through a series of activities that reflect, as best we see it, the full breadth of the kind of DH work students are likely to do inside and outside of faculty positions, in and out of the university. These activities fall in a few areas – DH community and values, teaching and learning, research management and infrastructure, and humanities programming and design. The students work on a range of activities, individually and as a group to explore these topics.

They produce collective statements of values and practices as a part of the unit on community building. You can see here the charter put together by the most recent cohort of students to that effect.

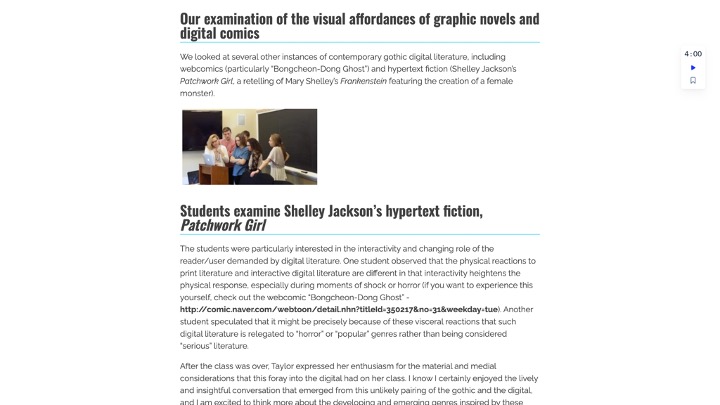

They design introductory DH workshops based around their interests and road test them with the community. These teach to learn activities are a space both to explore a new area of interest within DH as well as an opportunity to think through some issues in digital pedagogy.

The students also propose speculative research projects and DH events, and they carry out a series of technical exercises culminating in a DH hackathon to practice their computational skills. In case you’re interested in such details, the funding model has been engineered with the graduate school to replace a students’ teaching obligations for the year, which equates to $10,000 per student annually to free up the equivalent of ten hours of their time.

The Praxis fellowship is meant to give new students a transformational experience that will launch their connection to digital humanities. For higher-level students we offer a yearlong fellowship meant to be a full year of support in the sixth year of their PhD program. Students applying propose an individual digital research project of their own design, usually related to their dissertation, and they apply to work with a point of contact in the Lab on this project for a year. We try to adopt the principles of agile project management complete with scrums and biweekly sprints, both to get the project done but also to train the students in how to carry out this sort of work in the process. The kinds of projects we support run the full range of library services.

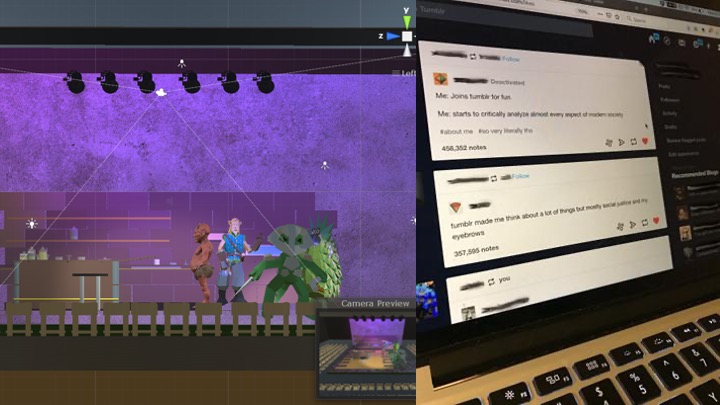

These projects range from problem solving and computational–a linguistic anthropologist had a box full of external hard drives of Tumblr posts that she needed help accessing and then subjecting to large-scale analysis–to technological and speculative–an English student used a mocap suit to create a VR “archive” of performance movement in theatrical productions.

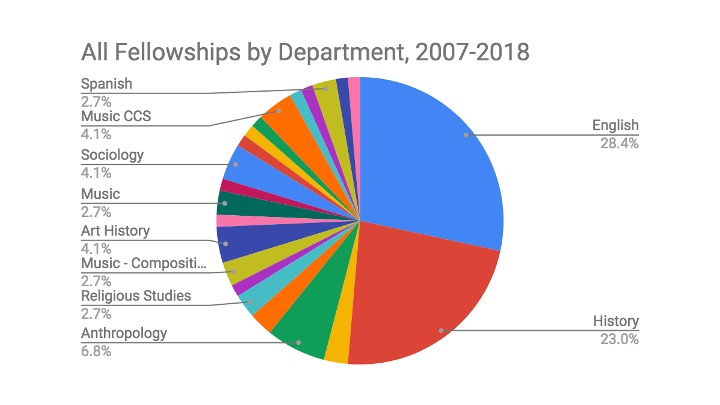

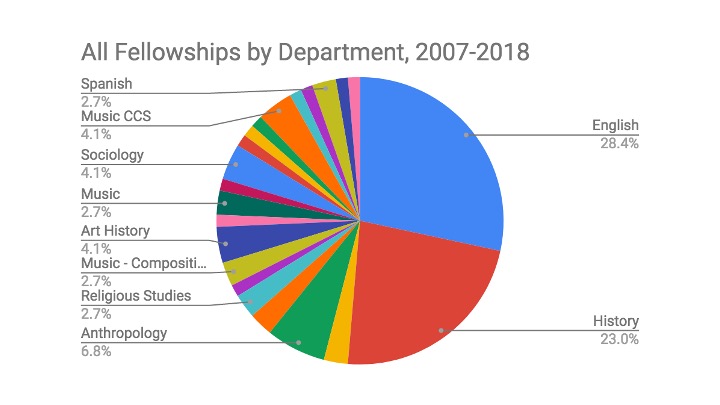

Here is a departmental breakdown in our fellowships as of a few years ago. I want to make sure to credit Rennie Mapp and Veronica Kuhn as key contributors to efforts to collect this data. One thing about our coverage - even though it looks like English and History dominate numerically, statistically music and art history are probably the most saturated because they are much smaller programs.

These are just our most well-funded fellowships. We also employ students on a wage basis as critical making technologists, as GIS interns to assist with spatial projects, as project managers to help assist with our community, and as interns assisting the production of 3D cultural heritage data. A full range of things depending on staff availability and funding. Happy to talk about any of those in Q&A. It’s perhaps worth noting, though, that the bulk of our student programming is weighted towards both PhD students and towards students developing original research. I actually think this is not a good thing – a longstanding goal of mine has been to develop a broader range of entry-level programming where students can apprentice on projects to gain skills and experiences, particularly for MA students who might have more limited time and resources.

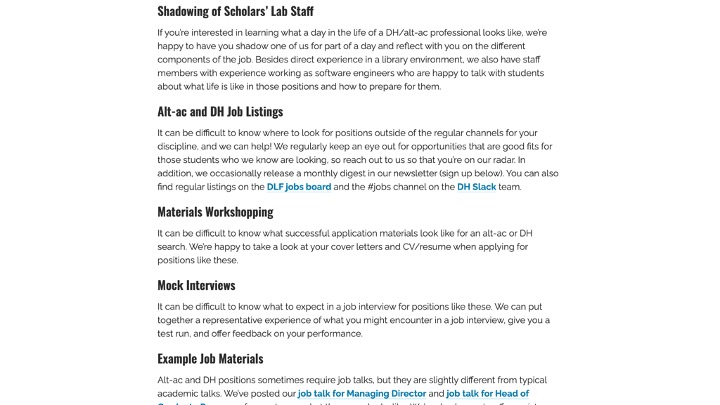

Common to all these programs and experiences is the goal of giving students real technical training through deep collaborations that they might not otherwise get in other parts of the university. We explicitly envision our space as a training space for a range of careers, and some of the work that we do involves helping students think about how to frame their work with us for the job market. We circulate our own job materials, share a range of job postings with our students, offer to workshop cover letters and CVs, give mock interviews, and more. We also collaborate with the Provost’s office to strategically position our own programs with organizations across campus who share a similar mission towards student professional development.

This is all in the service of helping students design the futures they want. We view it as part of our mission and our pedagogy that we help students not just with their own research and teaching but also with helping to envision how this work will give them a path into the future that they hope to see. Of course, it’s just good teaching to want your students to succeed. But we see this work as part of a larger project of developing our position in the library as a space for equitable, inclusive fellowship. In short, we view our teaching as necessarily bound up and entangled in the broader crises shaping higher education. We cannot teach our students, now, without recognizing the broader toxic environments in which they find themselves.

I often use this image from Futurama as a short-hand for this concept. We’re not in the business of treating students like heads in jars, isolated from the broader world. Teaching DH, for us, does not mean just teaching DH. It means teaching the whole student. And students right not are dealing with a lot. This means we have an obligation to engage in the broader struggle for justice and equity at the university. It means we have a responsibility to situate DH for our students in the broader context of what they want to achieve with it and why.

The close connections between our two fellowship programs and the PhD experience come from strategic attempts to stretch our own resources, but it of course is a choice that excludes MA students. This point of exclusion is one worth dwelling on further as I start to talk a little more about how we cultivate our community specifically in a library context. We are fortunate to have a generous amount of funding that we can direct towards students. It is never enough. For every data point that went to this graph, every person, there are two or more good people we had to turn away. This has been a point of tension at times with some of our library colleagues who rightly see the mission of the library more generally as one of equitable access to all. If we take both our library context and our goals of ethical and inclusive education seriously, we have as much an obligation to the students we cannot take into our named fellowships as much as we can. We work hard to try to remember, make space for, and invite into the space those who we have to reject. The professional development options that I mentioned above? They’re available to everyone at the university. We specifically reach out to rejected students and offer opportunities when we can.

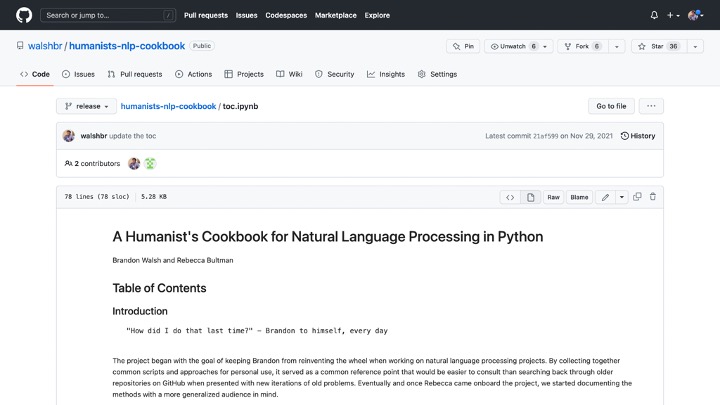

Part of this just involves keeping an eye open for members of the broader UVA community who might be interested in collaborating. I’ve personally engaged one student from our broader community in a book project, for example, which you can see before you. Rebecca Bultman and I entered into a really fruitful publishing partnership over the course of a couple years, and this emerged from our shared interests rather than through any specific fellowship program. All of this is to day we try to pull these students into our community in various ways.

Just as a practical point, here are some examples of the ways that we try to develop community with our students. We ask them to co-sponsor and co-plan events with invited speakers. We offer them space for activities when it might otherwise be difficult to secure locations to do what they want to do. We of course offer funding for a variety of things. But there are also things on this list that might seem to map less clearly on what we might describe as essential library services. Board game lunches. Free coffee. Dog hangouts. Food labs. Hackathons. This is to say - while funding is one very important way we can support students, we work hard to use the fellowship application process as a litmus test for who has interest in our community. And we try to connect the broader range of our services to those who can’t be included in our fellowships for whatever reason.

There is sometimes an even more fundamental point of tension with our institutional home. We are a library.

Why are we doing these things? Why, in particular, should a library be in the business of offering fellowships like these to students? I’ve already spoken to the clear interventions that our programs offer in the way of research and teaching, in information literacy and technical skills, in job preparation. But our students most commonly cite our status as a library, as a space apart that they treasure. We offer a space separate from their departments in which they might otherwise become siloed during their time at UVA. A community apart, with library faculty and staff that they might not otherwise meet. Developing that community is real labor, it has real payoffs, and it is essential work. It’s also work that libraries are uniquely situated to offer, being that we intersect so regularly with the departments but work in parallel to them.

This is something that is very personal to me. I did my PhD at UVA, in the English department. When I was a student, I remember being shocked when I heard about my friends taking fellowships in the Scholars’ Lab who were receiving workshops on budgets and grants. When I got involved in the lab later, the library offered me a space to learn things wholly different than I was getting from my degree. I remember tentatively asking the Head of R&D in the Scholars’ Lab at the time if a new DH job posting was something I might be in any world qualified for in the future. He enthusiastically helped me through this application process that took me to Washington and Lee University as a postdoc. These experiences quite literally transformed my life. I now direct those very same programs in which I participated. But that would not have happened if I hadn’t encountered a community ready to nurture my imagination rather than close it off. To say yes rather than no. This slide was to some degree an excuse to fit a cat in, but I think it also offers a useful metaphor for what the library can be for students. Is the cat about to eat that plant? help it flourish? Who can say?

More than any specific technical program or skills acquisition, our students often speak of us as an oasis in the center of an otherwise hostile university, as a space where they are free to grow into such possibilities for the first time. In Jacqueline Wernimont’s terms, we offer students a space to survive the university while we seek to transform it. That survival takes all sorts of different shapes for different people. For some, it is actual material wellbeing in the form of financial support. For others, it means research assistance. Or a sympathetic ear to difficulties with a dissertation director. Or showing up to a union action in solidarity. Or joining that same union! Or offering an expert read on dissertation material separate from disciplinary assumptions and pressures. Offering an actual, physical space in which they can work and exist in a university that is otherwise very reluctant to give up space. We can either view these things as separate from and secondary to the mission of the research library or we can embrace them as real assets that librarians can bring to the support of students. But in order to do any of these things, we first have to get students in the door. And then we have to build their trust.

Amanda

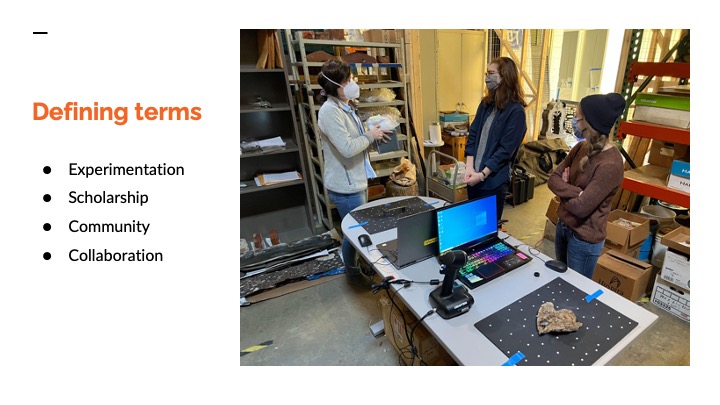

Now that we’ve given you an overview of what Scholars’ Lab is, we’d like to go into more depth on how we define several terms we’ve used repeatedly today: experimentation, scholarship, community, and collaboration. How we think about these terms and build them into our daily practices, gets into the whys and hows of interventions like the ones Brandon just described.

Digital humanities work has taken the form of early computing punchcards and CD-ROMs decades ago, or database and website interface heavy work more recently. But I’m personally not attached to whatever comes next needing to necessarily be “digital” (or called “DH”). As I mentioned before, there are research questions in all fields that rely on humanistic expertise, and we want to make sure our expertise is available to anyone, regardless of where their work sits or what they call their field.

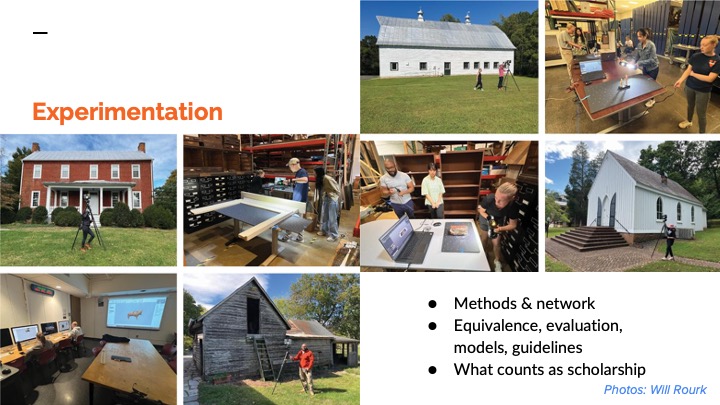

To me, an experimental mindset is even closer to the core of what SLab is, than DH or digital scholarship (but it was DH that got us to this thinking, and one of the key ways we experiment!). Three areas of experimental approach are key to what we offer:

First, a capaciously experimental mindset in how we pursue our research questions. Openness to thinking creatively about what formats, tools, and methods can best help you explore a research question is complemented by skill in staying aware of possibly applicable methods, tools, and other good from beyond your discipline. DH has historically been good at creating conferences and other networks that help humanists discover useful applications of approaches from other fields and outside academia.

Second, SLab supports the practical steps to that experimental mindset actually thriving within the academy. We’re experienced with communicating about and advocating for understanding of a variety of ways to do and share scholarship, digital or not. This includes taking a teaching rather than defensive stance, when convincing departments when such work should be accepted as equivalent to class projects, dissertations, or tenure and promotion. We can teach how to evaluate experimental work as scholarship. We’re familiar with the professional guidelines and model experimental scholarship that already exists, to provide inspiration, or help a scholar assess risk vs. reward.

Third, this experimental expertise helps us constantly expand not just what methods and formats are possible for our scholarship, but what “scholarship” itself can and should mean; who we think of and resource as scholars; and what that means for the work we must do.

In Mark Sample’s piece titled “When does service become scholarship?”: he argues that “a creative or intellectual act becomes scholarship, when it is public and circulates in a community of peers that evaluates and builds upon it”.

I’ve rephrased Sample’s work for my own definition: Scholarship as one part critical thinking, plus one part community—the work of communicating what you’ve learned, and assisting toward the just conditions that let the most diverse community of fellow learners possible inform, critique, learn from, and build on your research.

I like how these definitions both make research just half of scholarship, rather than synonymous with scholarship, bringing the scholarly community into focus as the motivator of our research work.

In my definition, we’ve got this critical thinking part of scholarship—the “work” we do to learn and make knowledge, accomplishable through many methods, including research, writing, coding, building, and more.

And we’ve got this community part of scholarship: that you need to communicate your knowledge work so others can learn from, critique and improve, and build on it; and that community needs your participation in advocacy toward conditions of access, equity, and care that truly allow everyone to have the opportunity to safely and fully participate in this collective knowledge making.

These definitions of “scholarship” carry with them implicit belief that the work of care, respect, mentoring, amplifying of your community members is not just a “nice” characteristic that should take second place to “rigor”.

Community carework is a necessary task of fully being a scholar, and participating in the scholarly project of collective knowledge-making. We need to strive for the conditions that make learning and sharing knowledge more accessible to everyone, extending beyond more obvious “life of the mind” requirements toward all aspects that impact learning, like a thriving wage and steady access to healthy food. In SLab, we’ve seen impressive work made possible when we’re able to fund a student so they don’t need to balance studying with us with also working a job, or able to make certain the university has disbursed their stipends or paychecks on time, or getting faculty a course release so they can work with us throughout the academic year instead of needing to drop work when it isn’t summer.

We’ve seen that workplaces that are safe and affirming of every person’s expertise allow staff to create fantastic services and scholarship. When we work to get people an environment with their material needs met, where they see their contributions and knowledge valued, where there are safe ways to ask for learning and resources without losing status, where experimentation and failure are understood as good steps toward learning, good scholarship and research follow. Scholars’ Lab is not anywhere near perfect at this, nor am I, but striving toward better workplace and learning conditions is part of what we understand and resource as scholarship, rather than an unrelated matter.

So, what can attention to justice and care look like in the digital humanities, and in Scholars’ Lab?

For just a handful of examples, DH was where I found people doing work like the Collaborators’ Bill of Rights, A Student Collaborators’ Bill of Rights, and the Postdoctoral Laborers Bill of Rights, all co-authored statements guiding good credit, collaboration, material resources for collaborators, and similar practices.

Our DH scholarly org, the Association for Computers and the Humanities (or ACH), was the first scholarly org I’d been part of that really forefronted social justice advocacy in how it defined its mission and the main actions supporting that mission, rather than as side projects and reports.

At a recent ACH conference, Brandon partnered with SLab Fellow Crystal Luo to speak about opportunities they’d identified for building collective power and recognizing labor rights within DH. Multiple DHers at UVA are members of our state higher ed union or other worker collectives, and bring attention to power dynamics in the library and academy to how we design and improve policies and practices shaping experimental scholarship at UVA.

Over the history of the lab, we’ve moved from closer to a traditional model of service like concentrating on providing technical work behind the scenes for faculty-led grant projects, to focusing on truer research collaborations among staff and faculty.

We strongly believe investment in the direct practice of experimental methods is the key to transformative experiences for individual scholars. It’s also the best leveraging of our limited resources on behalf of our community. We frame this as building things with people (e.g. as peer scholars, co-PIs on grant proposals), not for people.

We try to prepare our collaborators to own their own projects for many reasons:

- building confidence in their skills, so people can be practitioners in their own right

- increasing the number of folks on campus who can help train others

- helping everyone grow their collaboration skills, modeling respecting the expertise and labor of all research participants

- avoiding over-dependence on expert staff when you want to do something with your own project

Because we are always working at capacity nowadays, we additionally try to use our staff values charter to prioritize potential longer-term collaborations that match our values. The public-facing version of our charter on our website needs an update to match how our work has evolved over the past 5 years, but it still captures our current shared belief in helping folks take agency and ownership over their DH work, our shared commitment toward improving social equity and care, and our continuous framing of our focus being foremost on people, rather than on projects.

Brandon

This is often a hard sell – we trade quantity of consultations for deeper engagement with a smaller number of people. Rather than helping students grind out their projects (or do so for them) we tend towards slow, deep collaboration. But this is also a rewiring of how much academic work is framed. Even as PhD programs engage students in slow, deep methodological training, they often drive towards products: the prospectus. The CV. The dissertation. Our Praxis program, for being project-based work, often lends itself to similar questions. Just last week, applicants to next year’s cohort asked what the current students were working on? What projects were they building? My answer is always that these questions somewhat miss the point of what we’re trying to do. This is not to say that projects don’t take place – they happen! But they’re not the central focus of what we’re doing.

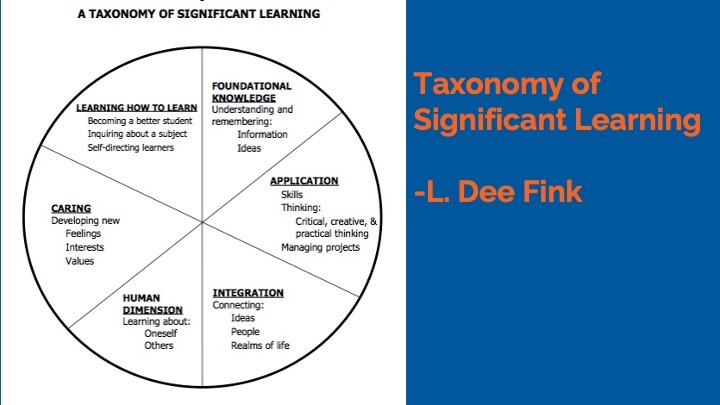

My primary research is on digital pedagogy, so if you’ll indulge me a slide in that direction – this is a diagram by way of L. Dee Fink’s Taxonomy of Significant Learning. It’s useful for reminding us of all the different component that make up learning experiences for students. When our own Center for Teaching Excellence uses the diagram, they offer it as a counterweight to what happens all-too-often when we design a course or a workshop. We settle into the upper-right portion of the pie: what are the readings? The topics? We don’t spend enough time thinking about the why, the how, to what end.

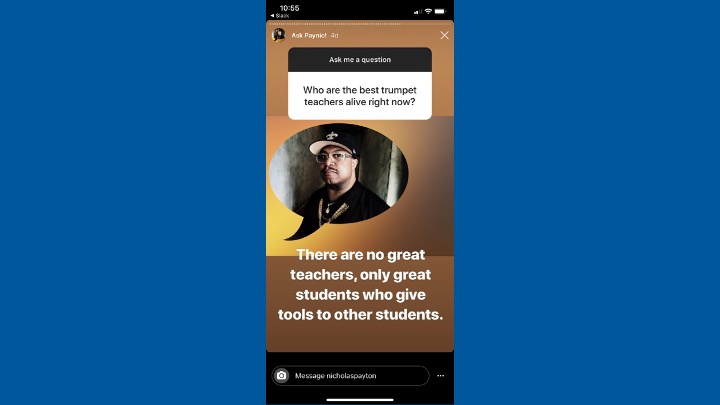

So what are our students working on? They’re working on their lives. What is the Lab working on? We’re working on the students and how to serve them as best as possible. More specifically we’re working on ourselves, on being better for them. That is to say, one of the ways that we engage praxis over product is by making sure that our processes are flexible and serve the needs of the students by really engaging them in the learning process as co-collaborators. I am quite fond of this quote from jazz trumpeter Nicholas Payton: there are no great teachers, only great students who give tools to other students. Another way of framing this would be to invoke Paulo Freire and say that we regularly challenge the banking model of education, where we as instructors deposit information into our students who then regurgitate it later. Instead, our goal is to approach students as equals, to recognize what we can learn from each other, and to work together to incorporate their own interests into a transformative process that grows with them over time.

This is all somewhat theoretical, so here are some practical ways in which we practice this. Rather than approach students with a project and ask them to implement it, teaching activities often grow from student interests. We usually recommend Reclaim Hosting for server space and digital projects so projects so student work can grow, move, and leave with students. Our students do some of the teaching in our fellowship process, learning about a corner of DH on their own and teaching it back to us. Rather than offering much in the way of one-off, service-oriented, drop-off work for students or faculty, we tend to favor longstanding collaborations and deep engagement. It should be clear that there are some real downsides to this work. We often struggle to meet demand, and some patrons simply don’t have the time, energy, or desire for a project idea to grow into months of biweekly meetings. This approach also requires a lot more work to be flexible and change plans to meet collaborators’ desires. The payoffs, though, often take the form of lifelong collaborations. New people drawn into library careers who might never have made it there in the first place. And deep, experiential learning that can, hopefully, still produce useful products along the way.

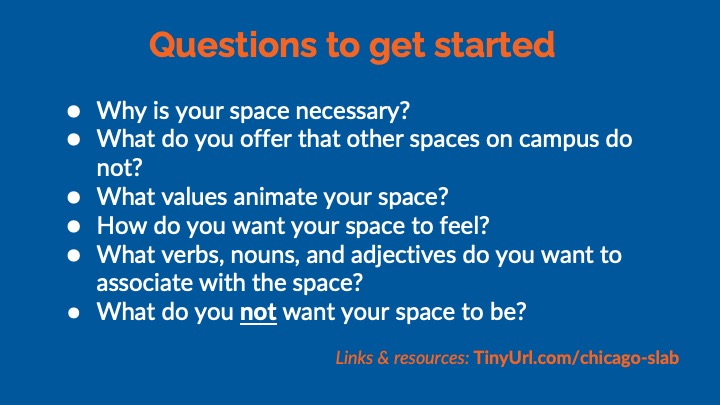

In short, the Lab is a space that tries to foreground its values through its actions and tries to meet its community where they are. The values and the mission come first. The programming second. In the context of this talk, we’ve explicitly framed ourselves as community-designed, centered, and driven. It’s all about the people. To abstract things out a little more, as we know you are in the process of designing your own center for digital scholarship, we’ve tried to offer some lessons from our own work in this area. But ultimately you’ll have to find your own. We would submit to you that you should start with the values you want at the center of your space. They will help determine everything else: programming, how to use your budget, needs, timelines, etc. So I know we are about to start Q&A, and there is plenty more that we could say about the Scholars’ Lab. But given that you’re hoping to learn from us, the teacher in me wants to offer a little takeaway homework for you as you design your own space. I thought we could close with some questions for you all.

- Why is your space necessary? What does it offer that other spaces on campus do not?

- What values animate your space?

- How do you want your space to feel?

- What single verbs, nouns, and adjectives do you want to associate with the space?

- What do you not want your space to be?

Our advice to folks developing a new digital center always involves some version of these conversations. Get your key team together, have frank conversations with each other about your values, and let those begin to sketch the outline of a structure. You’ll have plenty of time to animate that space with activities and programming. But for a space to be significant on campus, your community will need to know why you exist in the first place.

Thank you!