Pedagogies of Transparency: Part One

07 Apr 2025 Posted in:digital humanities book pedagogy scholars lab What follows is material drawn from a larger book project I’m working on about an approach to digital humanities pedagogy that intersects with administrative policy to work towards a more equitable landscape for higher education. I’ll be blogging pieces of it as I go, so stay tuned for more related work in the future. Keep in mind, though, that I will likely be blogging about other topics intermittently as well. You can find book-related posts here. Happy to hear feedback, either on social media or by email at bmw9t@virginia.edu.

Since 2017, I have run a fellowship program out of the University of Virginia Library’s Scholars’ Lab called the Praxis Program, a yearlong project-based introduction to digital humanities for graduate students. While the staff develop a framework for the year that best matches what we see as the needs for professional development in the interdisciplinary field of digital humanities, the students adapt this curriculum based on their own interests with a variety of collaborative and individual projects. The activities undertaken by the students are broad and varied, as described by the program’s curriculum page:

- A group charter, a statement of values and practices we will adhere to as a community

- A personalized plan for self-study throughout the year meant to take advantage of the resources in the lab

- An individual teaching plan for a digital humanities workshop based around the students’ interests

- A digital humanities teaching statement

- A speculative personal project proposal for what comes next for an individual; to be workshopped by the group

- Activities meant to exercise technical and design thinking as they relate to humanities problems

- Spring hackathon as a group

- Final presentation to a local audience

- Two blog posts

- At times, large-scale and named group projects (2024)

These activities are quite loosely defined: students can take them in whatever direction feels most urgent and important to them, and the outcomes usually come to reflect their own individual and collective research interests. While the program has changed shape numerous times of the years, it has always been an attempt to craft a framework for students to fill with their own ideas. In this mode, we adopt our own colleague and Praxis staff member Jeremy Boggs’ carrier bag theory of digital humanities: “Whether we realize it or not, much Digital Humanities work involves making and sharing these containers of things that are, and can be used, to tell stories” (2018). Rather than hand our students something premade, we weave a bag together for them, a pouch in which they can deposit their own experiences, hopes, and dreams. And, in arranging these elements, we hope that students discover new stories about themselves.

The process by which we offer students the freedom to design their own professional development experiences is a complicated bit of alchemy. At times, we offer distinct prompts that set parameters, as in our unit on digital pedagogy that asks students to design a pencil and paper exercise related to their own research. In other cases, we ask students to discuss their shared interests, to develop a theory for what they share as a group that the staff will then take and shape into a collective activity for them. Across the board, these pedagogical moves frame the program as fundamentally an exercise in student self-governance, an attempt to give over, as much as we can, control of the program to the students. We shape a container and ask our students to fill it together.

When given the space to do so, students have consistently driven the curriculum in a single direction. Across the board, each year, students have used these moments of intellectual freedom to critique, explore, and render transparent the workings of the university to the public. Students are hungry to understand—and push back on—the nature of their institutions. They recognize, at some intuitive level, that the highly manufactured imagery handed to them during prospective student weekends only tells part of the institutional story. As discussed in the previous section, budgetary discussions can offer one angle of approach for intervening in the embedded pedagogies of the university. While budgets offer a means by which to critique and reshape the limited knowability of the neoliberal university, they might feel too administrative in focus, a challenge for teachers to include in teaching that takes place on the curriculum. Educators can bring the same spirit of administrative critique into the classroom by designing digital projects that deliberately work to demystify the university. Transparency can be both a pedagogical end as well as a research subject in its own right.

In what follows I discuss two collaborative student projects from the Scholars’ Lab as case studies in developing a practice of digital humanities pedagogy that pursues transparency. The first is UVA Reveal, an augmented reality project that offers counter-narratives overlaid on University markers that tell more institutionally acceptable stories. The second—Land and Legacy—examines UVA’s real estate purchases in the last fifty years in order to directly confront our University President’s strategic goals to be “great and good” in reference to the surrounding community. In each case, I argue that rendering this institutional knowledge legible for teachers and students is the first step in making it more just. By meeting opaque institutions with a pedagogy that aims at transparency about its workings, we can re-empower educators who might otherwise feel at the mercy of bureaucracy. Each of these projects was conceived, designed, and developed by students. A pedagogy that centers transparency is one that centers learners themselves.

In August of 2017, white supremacists marched through downtown Charlottesville, Virginia injuring dozens and murdering one young activist. The Unite the Right Rally famously led to President Trump’s comment that there were “very fine people on both sides” and, eventually, to Joe Biden launching his presidential campaign video by invoking Charlottesville. Much of the discourse surrounding the events in the coming months and years focused on Trump’s comments and the administrative failures that led to the Rally taking place. Police and the university had ample warning that the events would turn violent, but they utterly failed to act on this information to protect their community members.

Much of the public memory of the event overlooks the fact that the weekend’s events did not begin on the Downtown Mall that Saturday. Locals know that the violence began the night before when the white supremacists first gathered on the University of Virginia campus and marched with tiki torches while chanting “Jews will not replace us.” They encircled a group of counter-protestors consisting of students, staff, and community members around a statue of Thomas Jefferson, the university’s founder. When discussing the events with me, friends and family outside the city frequently expressed shock that white supremacists had come to town. Locals knew, of course, that they had been here all along. Two lead figures for the event were Richard Spencer, an alt-right celebrity and University of Virginia alumnus, and Jason Kessler, a white supremacist Charlottesville native.

When the Praxis cohort set to work in the fall of 2017, it was with the cloud of these community events darkening the conversations. The year also happened to be my first as Head of Student Programs. I originally pitched a project for the group based around the makerspace, an area of the lab that had been under-utilized by this set of students in previous years. It quickly became clear, however, that the students’ real interest was in reckoning with the conflicting feelings they had about the university, its identity, and its complicity in the aftermath of these acts of racial violence. In the interests of honoring the flexible spirit of our pedagogical framework, we emptied our carrier bag and offered the students the freedom to start again, to fill it with whatever stories they felt most moved to tell. The result of this work was UVA Reveal, a project that works to illuminate aspects of the University that it would otherwise prefer to keep hidden. As described by the students who worked on the project, UVA Reveal is an attempt by graduate students to better understand the institutional histories of their university:

The 2017-2018 Praxis cohort has moved the material history of UVA out of Special Collections and onto Grounds. Using Augmented Reality applications, our project, titled UVA Reveal, Augmenting the University, challenges the surface of our perceptions of objects and places. UVA Reveal thus explores otherwise hidden stories, histories, and questions surrounding objects and spaces at UVA. In doing so, we hope to prompt users to re-examine everyday environs and critically reflect on the structure, culture, mission, and history of the university. (2018)

Designed as an augmented reality app that a user can download to their phone, UVA Reveal works on specific UVA campus locations to provide supplementary materials and commentary from the archives that trouble the public institutional narratives about place. All spaces carry with them their own contested histories, and UVA Reveal attempts to give voice to what might otherwise go ignored or silenced. Where the institution might opt for a manufactured view of itself, the app is an attempt by students to reclaim their own knowledge of the campus by layering context onto it.

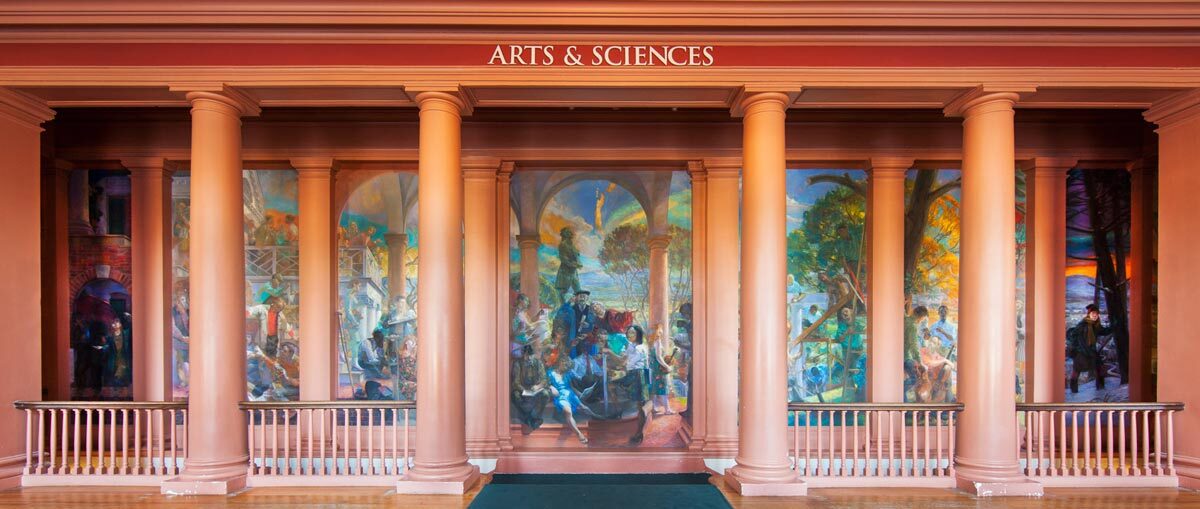

UVA Reveal invites students to see and notice the difficult institutional histories all around them. By forcing them to pay attention, the app asks students to consider the ways in which university narratives are always contested and subject to tense systems of power. For example, one location UVA Reveal augments is a prominent mural on campus that depicts a student’s journey through university life (Figure 1).

Figure 1: “The Student’s Progress,” a mural by Lincoln Perry in Old Cabell Hall at the University of Virginia.

The panels follow a red-headed child through her time as the University first as a youth, then a young woman and student, and then later in life as an alumnus with her own child back for a visit. Along the way, the painting illustrates her love of music and her encounters with students and community members. The painting also depicts scenes of debauchery including a mostly naked woman fleeing over the balcony of a faculty member as his wife climbs the stairs. The moment can be easy to miss, given the mural’s scale and location—the painting encompasses 22 panels on all sides of the length of the busy lobby in UVA’s music building. Once you notice it, though, the entire painting takes on a different valence. In the wake of an infamous Rolling Stone article describing instances of gang rape on UVA’s campus, faculty members have been particularly vocal about calling for its removal as a symbol of rape culture.1

Augmented reality applications work by assigning certain images as triggers for particular kinds of interactivity. When the user’s camera detects a selected image, a modified version of it will appear on the screen. In the case of the Perry Mural, the Praxis students chose two approaches. First, when viewed through the UVA Reveal interface, the app draws out elements of women’s experience, literally making them emerge from the mural as pop outs (Figure 2). By distorting the user’s field of view in this way, the app questions the original artist’s own tendency to submerge gendered violence and experiences in the larger work.

Figure 2: Depictions of sexual violence of “The Students Progress” that emerge towards the viewer when viewed in UVA Reveal.

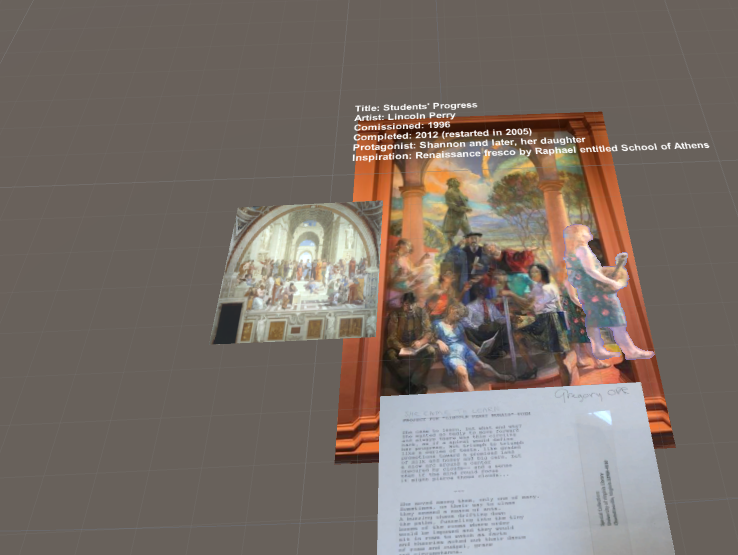

Figure 3: Screenshot of Unity interface that depicts the layering of contextual information on the mural including a poem by Gregory Orr and Raphael’s The School of Athens.

Second, alongside the app’s attempts to foreground gendered violence and the presence of women, UVA Reveal connects the target images to contextual information drawn from the university’s archives, in this case layering in a poem by Gregory Orr and Raphael’s The School of Athens (Figure 3). Doing so is an attempt by the students to understand the contested nature of the aesthetic experience of university campuses, which can at once be spaces of rich history, deep aesthetic beauty, and horrific racial violence. Perry’s mural is the subject of only one augmented location in UVA Reveal, which also works to complicate a range of spaces around campus: the Rotunda, a confederate cemetery, an African American cemetery, and more. Many of these locations contain complicated historical narratives, and the student project encourages visitors to slow down, take stock, and see with new eyes.

UVA Reveal’s about page describes an impulse to clarify and to understand as key to the project’s origin. The students started from a broad desire to explore public-facing digital scholarship but also “wanted to understand the connection between UVA’s history, Charlottesville, and access to education, broadly conceived” (2018). By providing contextual information that illuminates the university’s troubled relationships with race and gender, in particular, UVA Reveal offers users the chance to see again the university as it is. It also represented a new means by which the students could seize control over the institutional narrative. In this way, the project tapped into larger conversations about how technology can act at the intersections of—and exert influence over—history, art, and power. “Hello, we’re from the internet,” for example, was a series of guerrilla attempts by Internet activists to remake the Jackson Pollock room at the Museum of Modern Art into space in which they have a voice using augmented reality apps—without the permission of the institution (DeGeurin 2018). Efforts like these coalesced, in particular, around physical monuments and the stories they tell, as with the work by the Monument Lab to develop experimental platforms that allow for alternative historical context and narration.2 Rather than see their university purely defined by those in power, UVA Reveal gave students a chance to see through the limited knowability of the institution and render it known, on their own terms.

References

Boggs, Jeremy. 2018. “A Carrier Bag Theory for Digital Humanities.” Accessed July 31, 2024. https://jeremyboggs.net/carrier-bag-theory-for-dh/.

DeGeurin, Mack. 2018 “Internet Artists Invaded the MoMA With a Guerrilla Augmented Reality Exhibit.” Vice (blog), March 5. https://www.vice.com/en/article/8xd3mg/moma-augmented-reality-exhibit-jackson-pollock-were-from-the-internet.

Gordon, Bonnie. 2014. “The UVA Gang Rape Allegations Are Awful, Horrifying, and Not Shocking at All.” Slate, November 25. https://slate.com/human-interest/2014/11/uva-gang-rape-allegations-in-rolling-stone-not-surprising-to-one-associate-professor.html.

Miller, Allie. 2021. “Monument Lab’s New Overtime App Offers Augmented Reality Tours of Philly’s Art Museum Area.” Philly Voice. April 1st. Accessed July 31, 2024. https://www.phillyvoice.com/monument-lab-overtime-app-philly-virtual-tour-statues/.

Monument Lab. 2021. “OverTime.” Accessed July 31, 2024. https://monumentlab.com/projects/overtime.

Provence, Lisa. 2016. C-VILLE Weekly. “Teaching Moment: Renaissance Tradition v. Title IX.” April 13. Accessed July 31, 2024. https://www.c-ville.com/teaching-moment-renaissance-tradition-v-title-ix/.

Scholars’ Lab and Praxis Program. 2018. “UVa Reveal.” UVa Reveal. Accessed May 24, 2024. http://reveal.scholarslab.org/about/.

Scholars’ Lab and Praxis Program. 2024. “Praxis Curriculum.” Accessed July 31, 2024. https://praxis.scholarslab.org/curriculum/.