Pedagogies of Transparency Part Two

21 Apr 2025 Posted in:digital humanities book pedagogy scholars lab What follows is material drawn from a larger book project I’m working on about an approach to digital humanities pedagogy that intersects with administrative policy to work towards a more equitable landscape for higher education. I’ll be blogging pieces of it as I go, so stay tuned for more related work in the future. Keep in mind, though, that I will likely be blogging about other topics intermittently as well. You can find book-related posts here. Happy to hear feedback, either on social media or by email at bmw9t@virginia.edu.

UVA Reveal works to understand institutional legacies. The app is as an attempt by students to re-narrativize the stories the university tells about itself, its public spaces, and their inhabitants. But, in a way, the augmented reality project remains focused on the present: users must travel to the specific locations on campus in order to trigger the interactive context that troubles the historical narrative. A subsequent student project would go further, attempting to understand UVA’s relationship to physical space as a contested interplay of power and economics. For the 2019-2020 Praxis cohort, the central animating question was ostensibly quite simple: how much land does the university own, anyway? Finding the answer to this seemingly straightforward question required an immense amount of work: the students were forced to dive deep into the archives to negotiate a vast web of interrelated business entities acting on behalf of the university. The driving spirit for the digital project was clear: the students wanted to know their university in ways that were not immediately obvious.

As with UVA Reveal, the origin story for the project put together by the 2019-2020 Praxis cohort is one of the staff offering one direction and students choosing another. The goal of the Praxis assignments at this time was for students to shape a digital project of their own design, but over the years our Lab staff determined that students needed some degree of guidance in coming to these topics. Asking an interdisciplinary cohort with no prior association with one another—or background in digital humanities—to develop a project from scratch frequently brought frustration for the students who earnestly wanted to complete the task but lacked the tools to do so. The UVA Reveal cohort, for example, was given much more latitude to decide their topic but struggled for some time to bring their project into focus. For the 2019-2020 cohort year, the staff decided to offer two constraints:

- The students would be given a specific dataset to work with containing clear research questions, but the particular exploration of these questions would be left to the students.

- The students would be paired with a stakeholder within the library who could help give context for the work.

For this year’s cohort, the Lab provided the students with a set of ARCGIS datasets and map layers for UVA real estate acquisitions in Charlottesville and Albemarle County. As a part of the project, they engaged with Rebecca Cooper Coleman, UVA’s Librarian for Architecture and Co-PI for an initiative funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) to develop an equity atlas, a “data and policy tool for leaders and advocates to advance a more equitable community while helping citizens hold decision-makers accountable” (Association of Research Libraries 2023). The Charlottesville Regional Equity Atlas and the associated dataset provided some semblance of direction for the student work, broad research questions within which the project would take place. All the same, the staff left these connections largely implied, ready to be pursued or discarded as the students saw fit. It was the students themselves who chose to focus on transparency as a core principle and research topic in ways the staff could not have predicted while designing the assignment constraints.

The result of this work was Land and Legacy, a project that critiques the University of Virginia’s real estate acquisitions since the 1980s by contrasting the university’s public narratives about being a good neighbor with the negative impact of this expansion on the surrounding local communities. As with any good humanities project, Land and Legacy quickly pushed beyond the limitations staff tried to impose on it. The one dataset provided to the students quickly took them to others. Even as they tried to scope their work down, the students could not help but be led on an odyssey through the archives. The project’s data usage page describes a range of different sources including newspapers, meeting minutes, local open datasets, institutional websites, tax documents, architects’ plans, and more (“Our Data” 2020). Even as the project sought to explore how UVA’s relentless real estate acquisitions affected the local community, they first found themselves pressed to understand what those acquisitions were and how the university organized itself on a fundamental level.

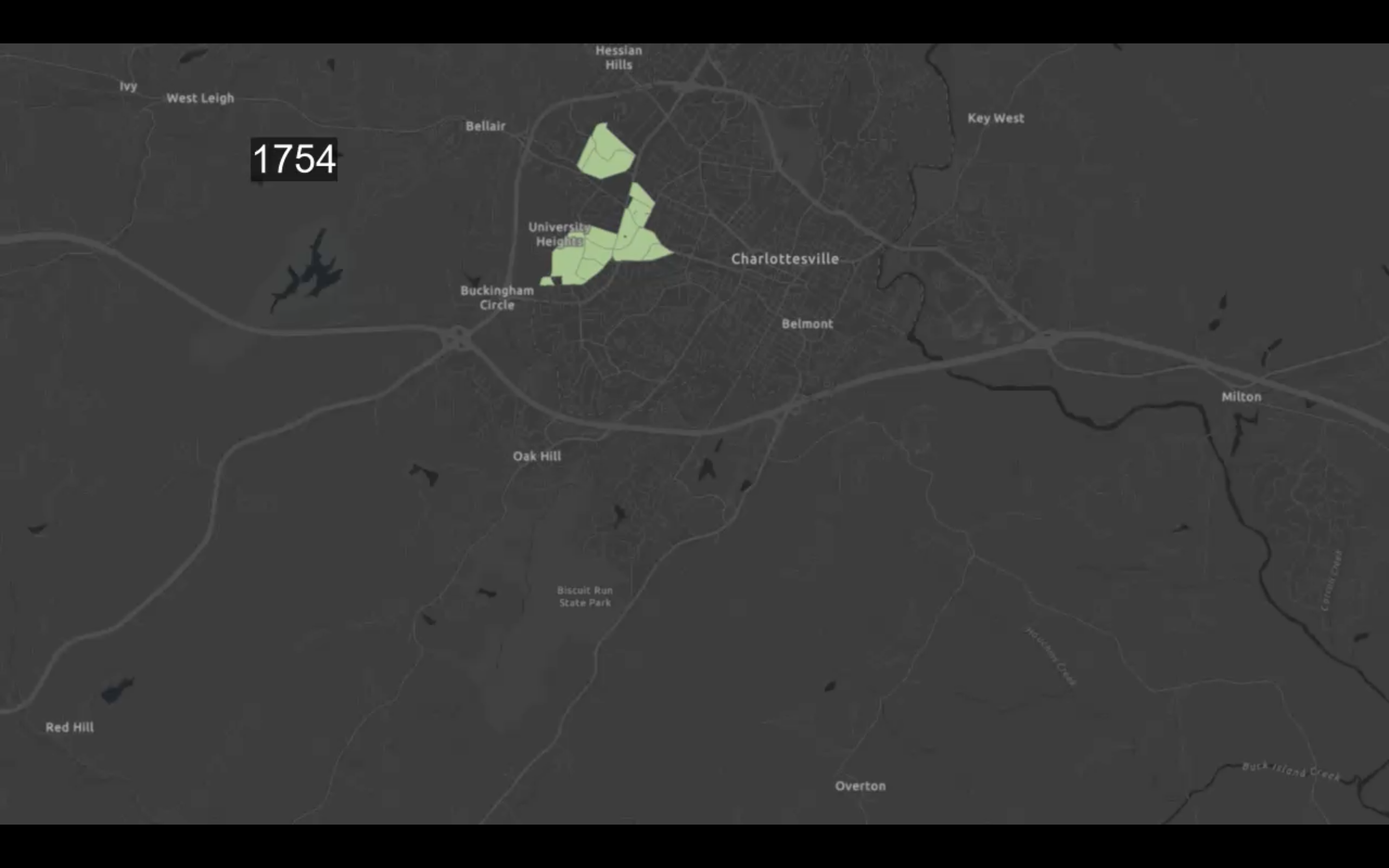

Land and Legacy’s central intervention was to illustrate visually and narratively the complicated history of the university’s reach. Doing so required the students to piece together a contested history of land acquisition that spanned centuries, involved countless university and local actors, and revealed a range of dispositions towards the land, the locality, and the legacy of the university. The University of Virginia’s cornerstone was not laid until 1817, and its founding is typically dated to 1819. But Land and Legacy actually dates the beginning of the university’s sprawling growth much earlier with the theft of land from the Monacan Indian Nation (Figure 1):

The University’s physical presence in the landscape began in the early 19th century with the acquisition of two parcels of land: 43 ¾ acres that would become the Academical Village and 153 acres that included Lewis and Observatory Mountains. Although these parcels were purchased from Virginia farmers, this land originally belonged to the Monacan Indian Nation. European settlers had displaced the Monacans from Charlottesville and Albemarle County by the 1750s, but they still traveled to important ancestral sites in the area. For instance, in his Notes on the State of Virginia Thomas Jefferson recalled seeing a group of Native Americans, presumed to be Monacan, near his home at Monticello to grieve at a burial mound that he later excavated. (“Foundations” 2020).

It is one thing to offer a land acknowledgement at the beginning of University meetings. It is quite another to spatially visualize the University’s long history of colonialism alongside its contemporary rhetoric about community. This long history can be difficult to conceptualize, so Land and Legacy opens with a gif illustrating the various land acquisitions.

Figure 1: Screenshot of animated spatial visualization from Land and Legacy project depicting real estate acquisition by the University of Virginia over time. This screenshot illustrates the status of UVA-related lands as of 1754.

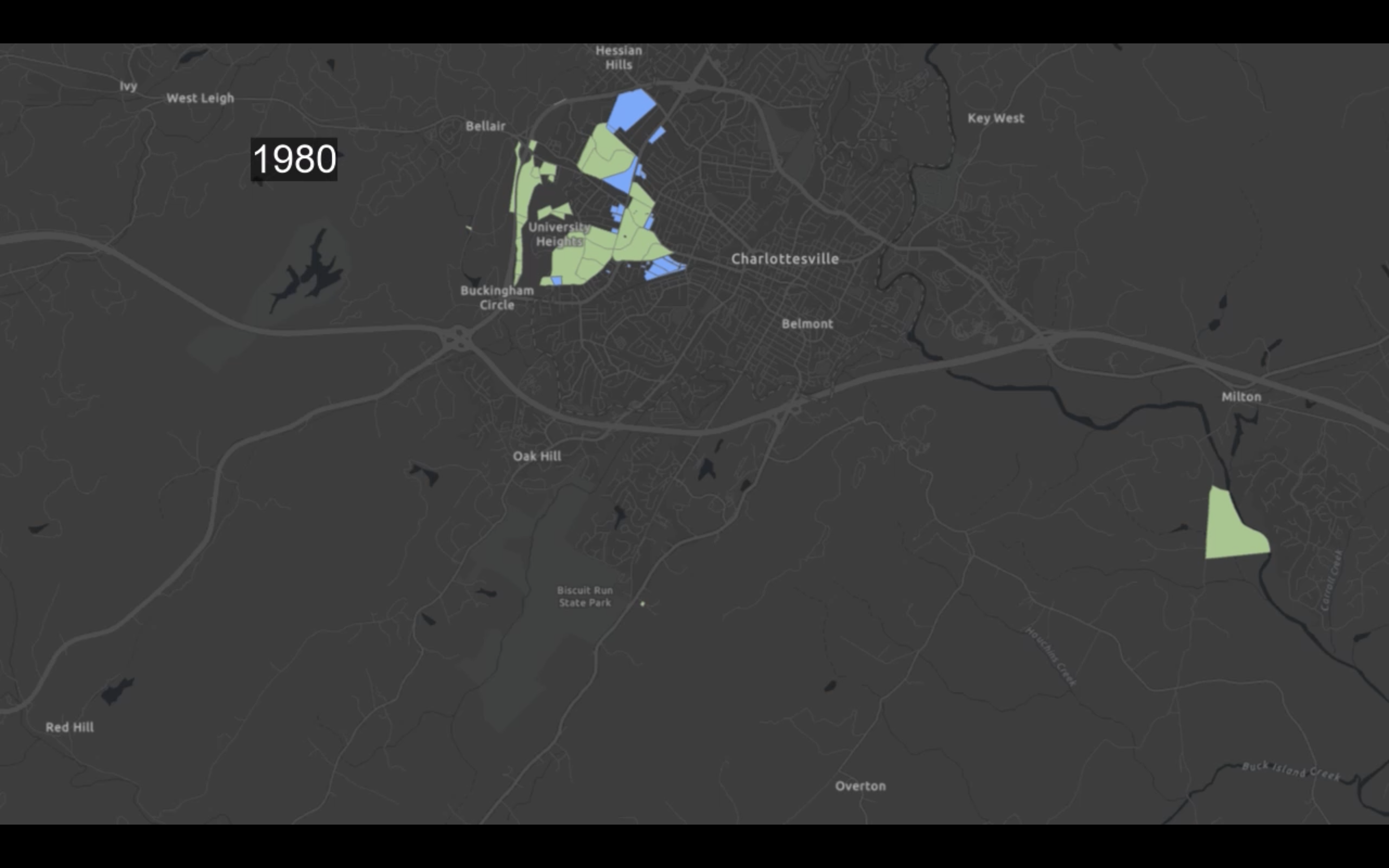

Figure 2: Screenshot of animated spatial visualization from Land and Legacy project depicting real estate acquisition by the University of Virginia over time. This screenshot illustrates the status of UVA-related lands as of 1980.

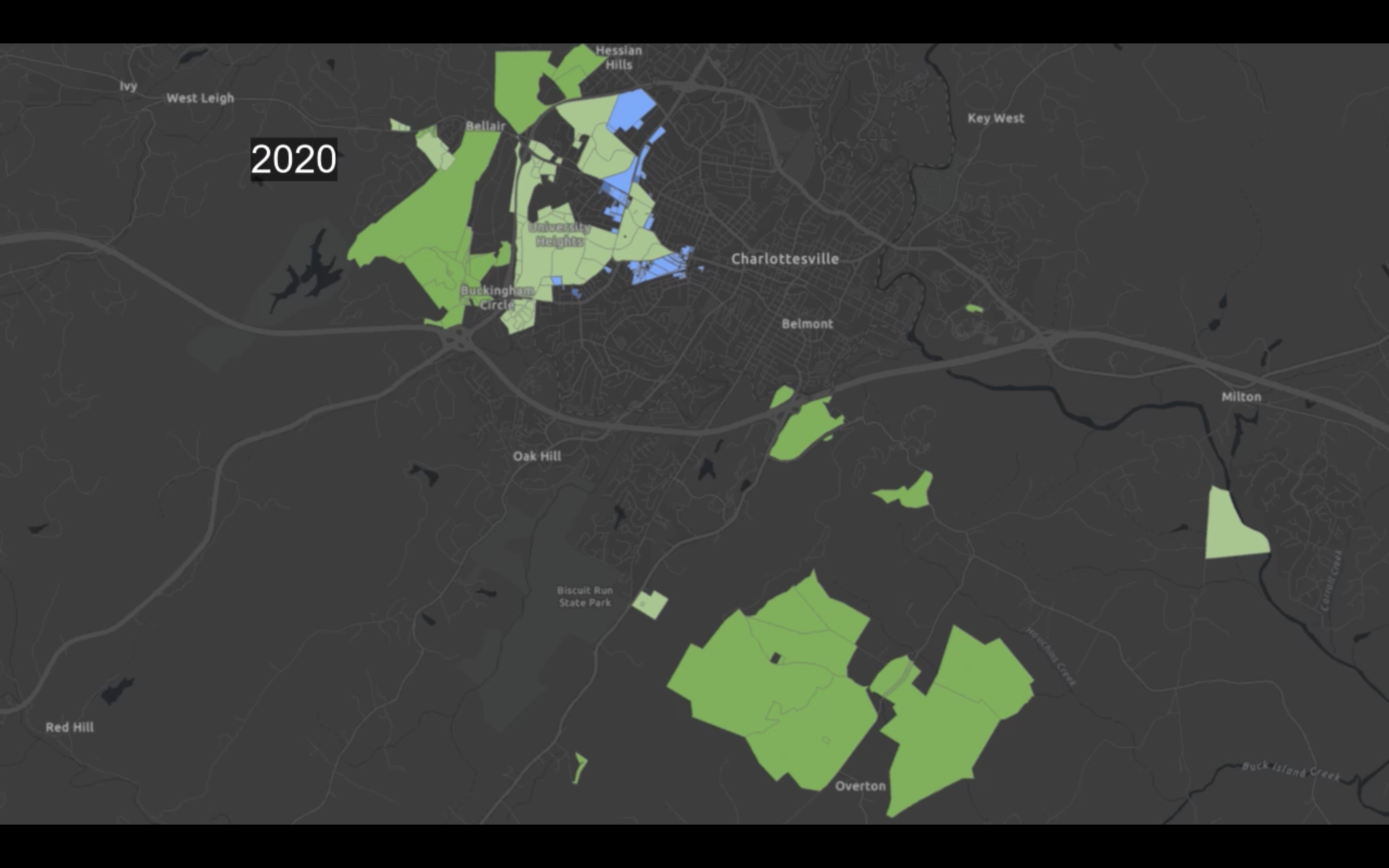

Figure 3: Screenshot of animated spatial visualization from Land and Legacy project depicting real estate acquisition by the University of Virginia over time. This screenshot illustrates the status of UVA-related lands as of 2020.

Land and Legacy focuses, in particular, on the period since the 1980s, which saw the university’s major efforts to be viewed as the premier American public university. As illustrated by the project’s animated spatial visualization, the university’s ambition was matched with an explosion of construction and land acquisition (Figures 2 and 3). The project goes to great lengths to show how this rapid development was contested, a source of tension between the university and its surrounding community. Local groups pushed back on these land grabs even as, importantly, they struggled to understand their exact nature.

The university’s real estate holdings are opaque by design. The students found it difficult to determine exactly what purchases the institution had made, in large part due to the complicated ways in which universities manage their dealings. As described on the Land and Legacy “Foundations” essay: “Since 1986, UVA’s real estate activities have been manage by a subsidiary, nonprofit 501(c)(3) corporation: the UVA Real Estate Foundation (UVREF), later incorporated as the UVA Foundation (UVAF)” (2020). The University used these legally distinct entities to manage their financial and physical growth, but, as the students found in the archives, “local residents have not always perceived them as distinct entities” (“Foundations” 2020). Clarifying this relationship and understanding the nature of the UVA Foundation became one of the main challenges of the project. The project started out with the goal of analyzing and critiquing real estate practices, but it wound up simplifying its aims considerably: just helping anyone understand this messy history was an end in itself. Transparency, alone, proved to be both worthwhile and immensely difficult. Land and Legacy started with a dataset about the university, but it developed into an attempt to demystify the nature of that institution, which had intentionally set up a structure that alienated its communities from understanding its actions. In this way, the pedagogy and practice at the core of the project aimed to reintroduce transparency to an overly opaque system, a value that ran in direct opposition to institutional goals. While UVA claimed to be great and good, a knowable member of the community, it was, in fact, acting in direct opposition to those values and doing so with an obfuscating cloud of bureaucracy.

Both Land and Legacy and UVA Reveal point to a pervasive interest among students in understanding and critiquing their spaces of teaching and learning. Rather than accepting manufactured institutional narratives, students hunger to develop their own, authentic ways of knowing their own communities. As Boggs notes, all digital humanities work is an effort to build containers for stories. These students saw the institutional containers presented to them as black boxes, impossibly complex and obscure entities refused to be known. They told one story but held another inside. These students, instead, helped to develop their own, transparent containers, ones that explained rather than obscured. The Scholars’ Lab staff partnered with its students in the service of re-knowing their educational organizations, critiquing them, and reshaping them. In the process they helped to develop a pedagogy of transparency. Such a pedagogy is one that refuses institutions attempts to obscure their institutional histories. Instead, a pedagogy of transparency co-creates new ways for students, teachers, and communities to re-examine the spaces they inhabit. It makes space for new ways of knowing, teaching, and learning.

As I have illustrated, the projects developed by the Praxis Program have always come into being through a complicated give and take with students, responsive to their needs and interests. This approach to curricular design is, itself, an attempt to be transparent about our own processes. In the staff charter, the statement of values that outlines the goals of the program, we write: “we will constantly re-evaluate the curriculum with an eye to building the best experience for the students” (2021). The program is not one in which we share a fixed syllabus at the beginning of the course and then unflinchingly march through it week by week. The curricula shared at the beginning of each semester often undergo tweaks based on student needs and feedback that result in new workshops, new modules, and new assignments. On a larger level, the program today would look unrecognizable to someone who was a member of the first two cohorts.1 When the program began, each cohort worked on a single collaborative project for the entire year. Now, instead, we incorporate a small, low-stakes project that takes place over the course of a month in the service of offering more concentrated training in project design and management, pedagogy, and community building. All of these changes have been documented on the Scholars’ Lab blog, where I, as Head of Student Programs, make a case for the changes to the program. These readings are later re-incorporated into the curriculum to expose students to the decisions made on their behalf.2 Put another way, we attempt to design and redesign the program’s pedagogy in public, in all of its administrative messiness. The hope is that this results in an experience that illuminates for students the possibilities—as well as the limitations—for the teaching administrator in the neoliberal university. It also helps to frame our work as always in process, always responsive to their needs. A transparent carrier bag—not a black box.

###

As this chapter has argued, institutions have pedagogies embedded within them, complicated networks of policies, expectations, and norms that give a gravitational pull towards specific kinds of educational experiences. The first step to challenging these pedagogies is to see them for what they are, to note their affects on our teaching and learning environments and how we might push back. Whether with budgets or with student projects, the teaching administrator is well positioned to help render legible those processes that might otherwise appear opaque to its community. In doing so, we can shape a new relationship with our students, one in which we begin to learn more about our institutions and the challenges they face for the work we want to do. We can meet the limited knowability and opacity of the neoliberal university with a pedagogy that champions transparency, that draws students further into the gears of their education without sweeping them up within them.

Teaching in the face of an inimical institution is immensely challenging work. The embedded pedagogies have a current to them, and teaching in your own way can feel like swimming upstream. The hope is that this book will offer a roadmap and guidebook for doing so. When met with bolted-down desks, we can instead sit in them facing the opposite directions and shape new communities despite the institutional pressure. This work can be transformative and invigorating, but it can also be fraught and painful. Those desks are rigid—they attempt to enforce a particular worldview on those who sit within them. Perhaps most challenging, they appear to be passive companions in teaching and learning rather than the active agents that they are. The classroom designed in this way purports to be a flat space, a container that we can fill with whatever educational experiences we desire. But as we have seen, the desks have an agenda. And the university is anything but indifferent to the kinds of education, politics, and community members it allows into its walls. Our first entry point for pushing back on institutional pedagogies was to counter their limited knowability with transparency. In meeting the active pedagogical will of the university, we introduce the second component of the stories neoliberal universities tell about themselves that directly challenges our ability to teach justly.

Universities claim to be neutral. They are anything but, and this facade of neutrality directly undermines our ability to educate.

Boggs, Jeremy. 2018. “A Carrier Bag Theory for Digital Humanities.” Accessed July 31, 2024. https://jeremyboggs.net/carrier-bag-theory-for-dh/.

Scholars’ Lab and Praxis Program. 2021. “Praxis Program Charter.” Accessed July 30, 2024. https://praxis.scholarslab.org/praxis-program-charter/.

Scholars’ Lab and Praxis Program. 2018. “UVa Reveal.” UVa Reveal. Accessed May 24, 2024. http://reveal.scholarslab.org/about/.

Land and Legacy, Praxis Program, University of Virginia Library, Scholars’ Lab, last modified July 31, 2020, https://landandlegacy.scholarslab.org/.

“Foundations.” Land and Legacy, Praxis Program, University of Virginia Library, Scholars’ Lab, last modified July 31, 2020, https://landandlegacy.scholarslab.org/story-1-foundations.html.

Virginia Equity Center. n.d. Charlottesville Regional Equity Atlas. Accessed May 24, 2024. https://www.virginiaequitycenter.org/charlottesville-regional-equity-atlas.

Association of Research Libraries. 2023. “University of Virginia Library—Community-Led Open Data to Address Inequality.” Association of Research Libraries (blog). Accessed May 24, 2024. https://www.arl.org/university-of-virginia-library-community-led-open-data-to-address-inequality/.

Walsh, Brandon. 2023. “The Shape of DH Work” July 3. Scholars’ Lab (blog). Accessed July 30, 2024. https://scholarslab.lib.virginia.edu/blog/the-shape-of-dh-work/