Collaborative Writing to Build Digital Humanities Praxis

04 Aug 2017 Posted in:w&l digital humanities talks pedagogy dh now [The following is the rough text of my short paper given at the 2017 Digital Humanities conference in Montréal.]

Thanks very much for having me today! I’m Brandon Walsh, Head of Graduate Programs in the Scholars’ Lab at the University of Virginia Library. I’ll be talking a bit today about “Collaborative Writing to Build Digital Humanities Praxis.” Since the subject here is collaboration I wanted to spend a few minutes here on my collaborators.

This work was begun at my previous position at Washington and Lee University’s library. My principal collaborator here is and was Professor Sarah Horowitz, from Washington and Lee University. We conceived the project together, co-taught the associated course, and her writing figures prominently on the project I will describe. The other names here are individuals, institutions, or projects who figure explicitly in the talk, whether they know it or not. You can find a Zotero collection with the resources mentioned during the talk here.

So. To begin. Emergent programs like those associated with the Praxis Network have redefined the possibilities for digital humanities training by offering models for project-based pedagogy. These efforts provide innovative institutional frameworks for building up and sharing digital skills, but they primarily focus on graduate or undergraduate education. They tend to think in terms of students. The long-term commitments that programs like these require can make them difficult to adapt for the professional development of other librarians, staff, and faculty collaborators. While members of these groups might share deep interests in undertaking such programs themselves, their institutional commitments often prevent them from committing the time to such professional development, particularly if the outcomes are not immediately legible for their own structures of reporting. I argue that we can make such praxis programs viable for broader communities by expanding the range of their potential outcomes and forms. In particular, I want to explore the potential for collaborative writing projects to develop individual skillsets and, by extension, the capacity of digital humanities programs.

While the example here focuses on a coursebook written for an undergraduate audience, I believe the model and set of pedagogical issues can be extrapolated to other circumstances. By considering writing projects as potential opportunities for project-based development, I argue that we can produce professionally legible outcomes that both serve institutional priorities and prove useful beyond local contexts.

The particular case study for this talk is an open coursebook written for a course on digital text analysis (Walsh and Horowitz, 2016). In fall of 2015, Professor Sarah Horowitz, a colleague in the history department at Washington and Lee University, approached the University Library with an interest in digital text analysis and a desire to incorporate these methods in her upcoming class. She had a growing interest in the topic, and she wanted support to help her take these ideas and make them a reality in her research and teaching. As the Mellon Digital Humanities Fellow working in the University Library, I was asked to support Professor Horowitz’s requests because of my own background working with and teaching text analysis. Professor Horowitz and I conceived of writing the coursebook as a means by which the Library could meet her needs while also building the capacity of the University’s digital humanities resources. The idea was that, rather than offer her a handful of workshops, the two of us would co-author materials together that could then be used by Professor Horowitz later on. The writing of these materials would be the scene of the teaching and learning. Our model in this regard was as an initiative undertaken by the Digital Fellows at the CUNY Graduate Center, where their Graduate Fellows produce documentation and shared digital resources for the wider community. We aimed to expand upon their example, however, by making collaborative writing a centerpiece of our pedagogical experiment.

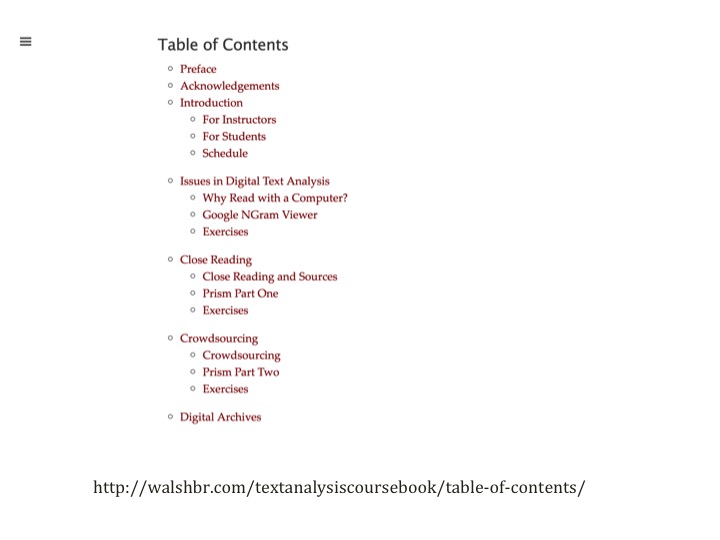

We included Professor Horowitz directly in the creation of the course materials, a process that required her to engage in a variety of technologies central to a certain kind of web publishing workflow: command line, Markdown, Git, and GitHub. We produced the materials on a platform called GitBook, which provides a handy interface for writing that invokes many elements of this tech stack in a non-obtrusive way. Their editor allows you to write in markdown and previews the resultant text for you, but it also responds to the standard slew of MS Word keyboard shortcuts that many writers are familiar with. In this way we were able to keep the focus on the writing even as we slowly expanded Professor Horowitz’s ability to work directly with these technologies. From a writing standpoint, the process also required synthesis of both text analysis techniques and disciplinary material relevant to a course in nineteenth-century history. I provided the former, Professor Horowitz would review and critique as she added the latter, then I would review, etc. The result, I think, is more than either of us could have produced on our own, and we each learned a lot about the other’s subject matter. The result of the collaboration is that, after co-writing the materials and teaching the course together, Professor Horowitz is prepared to offer the course herself in the future without the support of the library. We now also possess course materials that, through careful structuring and selection of platforms, could be reusable in other courses at our own institutions and beyond. In this case, we tried to take special care to make each lesson stand on its own and to compartmentalize each topic according to the various parts of each class workshop. One section would introduce a topic from a theoretical standpoint, the next would offer a case study using a particular tool, and the last would offer course exercises that were particular to our course. We hoped this structuring would make it easy for the work to be excerpted and built upon by others for their own unique needs.

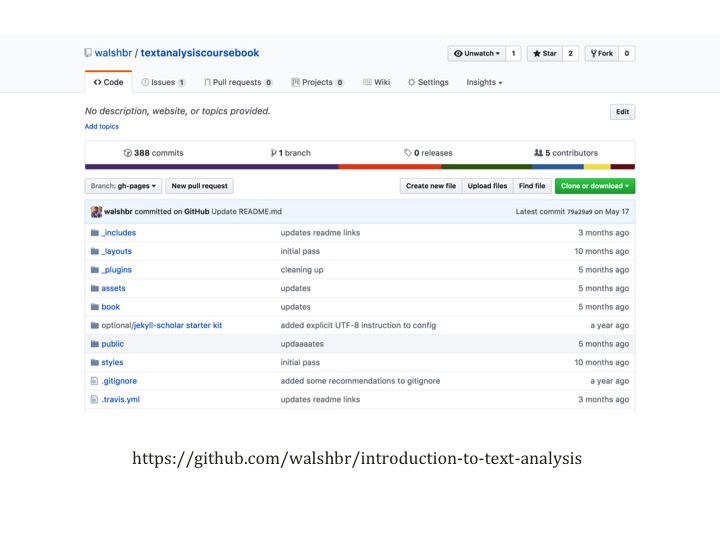

Writing collaborations such as these can fit the professional needs of people in a variety of spaces in the university. Course preparation, for example, often takes place behind the scenes and away from the eyes of students and other scholars. You tend to only see the final result as it is performed with students in a workshop or participants in a class. With a little effort, this hidden teaching labor can be transformed into openly available resources capable of being remixed into other contexts. We are following here on the example of Shawn Graham (2016), who has illustrated through his own resources for a class on Crafting Digital History that course materials can be effectively leveraged to serve a wider good in ways that still parse in a professional context. In our case, the collaboration produced public-facing web writing in the form of an open educational resource. The history department regarded the project as a success for its potential to bring new courses, skills, and students into the major as a result of Professor Horowitz’s training. The University Library valued the collaboration for its production of open access materials, development of faculty skills, and exploration of workflows and platforms for faculty collaboration. We documented and managed the writing process in a GitHub repository.

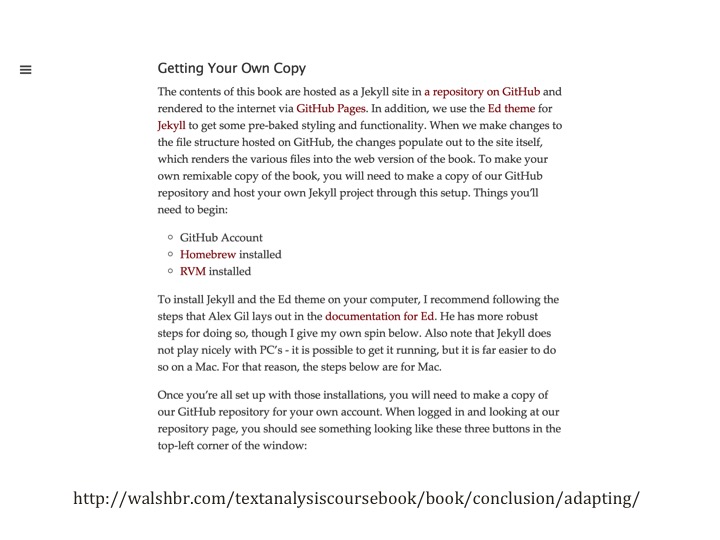

This versioned workflow was key to our conception of the project, as we hoped to structure the project in such a way that others could copy down and spin up their own versions of the course materials for their own needs. We were careful to compartmentalize the lessons according to their focus on theory, application, or course exercises, and we provided documentation to walk readers through the technical process of adapting the book to reflect their own disciplinary content. We wrote reasonably detailed directions aimed at two different audiences - those with a tech background and those without. We wanted people to be able to pull down, tear apart, and reuse those pieces that were relevant for them. We hoped to create a mechanism by which readers and teachers could iterate using our materials to create their own versions.

Writing projects like this one provide spaces for shared learning experiences that position student and teacher as equals. By writing in public and asking students and faculty collaborators to discuss, produce, and revise open educational resources, we can break down distinctions between writer and audience, teacher and student, programmer and non-programmer. In this spirit, work by Robin DeRosa (2016) with the Open Anthology of Earlier American Literature and Cathy Davidson with HASTAC has shown that students can make productive contributions to digital humanities research at the same time that they learn themselves. These contributions offer a more intimate form of pedagogy – a more caring and inviting form of building that can draw newcomers into the field by way of non-hierarchical peer mentoring. It is no secret that academia contains “severe power imbalances” that adversely affect teaching and the lives of instructors, students, and peers (McGill, 2016). I see collaborative writing as helping to create shared spaces of exploration that work against such structures of power. They can help to generate what Bethany Nowviskie (2016) has recently advocated as a turn towards a “feminist ethics of care” to “illuminate the relationships of small components, one to another, within great systems.” By writing together, teams engage in what Nowviskie (2011) calls the “perpetual peer review” of collaborative work. Through conversations about ethical collaboration and shared credit early in the process, we can privilege the voice of the learner as a valued contributor to a wider community of practitioners even before they might know the technical details of the tools or skills under discussion.

Collaborative writing projects can thus serve as training in digital humanities praxis: they can help introduce the skills, tools, and theories associated with the field, and projects like ours do so in public. Productive failure in this space has long been a hallmark of work in the digital humanities, so much so that “Failure” was listed as a keyword in the new anthology Digital Pedagogy in the Humanities (Croxall and Warnick, 2016). Writing in public carries many of the same rewards – and risks. Many of those new to digital work, in particular, rightfully fear putting their work online before it is published. The clearest way in which we can invite people into the rewards of public digital work is by sharing the burdens and risks of such work. In her recent work on generous thinking, Kathleen Fitzpatrick (2016) has advocated for “thinking with rather than reflexively against both the people and the materials with which we work.” By framing digital humanities praxis first and foremost as an activity whose successes and failures are shared, we can lower the stakes for newcomers. Centering this approach to digital humanities pedagogy in the practice of writing productively displaces the very digital tools and methodologies that it is meant to teach. Even if the ultimate goal is to develop a firm grounding in a particular digital topic, focusing on the writing invites students and collaborators into a space where anyone can contribute. By privileging the writing rather than technical skills as the means of engagement and ultimate outcome, we can shape a more inviting and generous introduction to digital humanities praxis.

References

- Croxall, B. and Warnick, Q. (2016). “Failure.” In Digital Pedagogy in the Humanities: Concepts, Models, and Experiments. Modern Languages Association.

- DeRosa, R. (2016). “The Open Anthology of Earlier American Literature.” https://openamlit.pressbooks.com/.

- Fitzpatrick, K. (2016). “Generous Thinking: The University and the Public Good.” Planned Obsolescence. http://www.plannedobsolescence.net/generous-thinking-the-university-and-the-public-good/.

- Graham, S. (2016). “Crafting Digital History.” http://workbook.craftingdigitalhistory.ca/.

- McGill, B. (2016). “Serial Bullies: An Academic Failing and the Need for Crowd-Sourced Truthtelling.” Dynamic Ecology. https://dynamicecology.wordpress.com/2016/10/18/serial-bullies-an-academic-failing-and-the-need-for-crowd-sourced-truthtelling/.

- Nowviskie, B. (2011). “Where Credit Is Due.” http://nowviskie.org/2011/where-credit-is-due/.

- ———. 2016. “Capacity Through Care.” http://nowviskie.org/2016/capacity-through-care/. Ramsay, S. (2010). “Learning to Program.” http://stephenramsay.us/2012/06/10/learning-to-program/.

- ———. 2014. “The Hermeneutics of Screwing Around; or What You Do with a Million Books.” In Pastplay: Teaching and Learning History with Technology, edited by Kevin Kee. University of Michigan Press. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.12544152.0001.001.

- The Praxis Network (2017). University of Virginia Library’s Scholars’ Lab. http://praxis-network.org/. Walsh, Brandon, and Sarah Horowitz. 2016. “Introduction to Text Analysis: A Coursebook.” http://www.walshbr.com/textanalysiscoursebook